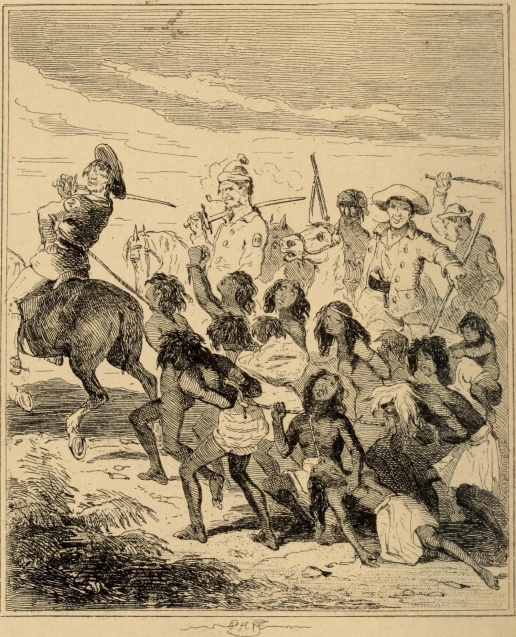

Illustration of Aborigines tied together at Myall Creek, 1838. Source: Sydney Living Museums

John Hubert Plunkett, an Irish lawyer and politician, has been described as an unsung colonial hero and ‘early legal celebrity’. His success in Ireland in the 1820s resulted in a reward of solicitor-general of New South Wales (NSW); he was the first Catholic appointed to high civil office in the colony. His career in Australia saw him partaking in a case that involved the slaughtering of the group of Aborigines known as the Myall Creek massacre in 1838. It is one of a number of massacres and attacks that involved the killing of Aborigines in Australia but what is unique about this massacre are the actions of Plunkett as prosecutor of the case. It is the only massacre where colonial settlers were convicted for the murders of Aboriginal people.

Among the primary sources used here will be articles from newspapers like The Australian and the Sydney Morning Herald, which highlight many of the racist views that were held throughout Australia during this period. These newspapers also used their platforms to support the settlers rather than Aboriginal victims. Irish involvement in Aboriginal violence cannot be generalised as the Myall Creek massacre conveys different aspects of of settler Irish relationships with the Aborigines. With the majority of colonists having a negative perception of the Aborigines, John H. Plunkett was clearly in the minority with his stance. His participation and persistence caused a mass reaction amongst colonists and the media. So who was this Irish immigrant that made an impact on Australian history? Why was his involvement in the Myall Creek trial so controversial? What did his involvement do for the relationship between colonists and the Aboriginals?

John Hubert Plunkett (1802-1869)

Plunkett was born in Mount Plunkett, County Roscommon, Ireland and originated from a family with aristocratic connections who were involved in the easing of the penal laws against Catholics.[1] He attended Trinity College Dublin, acquiring his B.A. in 1824. There Plunkett established himself, and two years later he was called to the Irish Bar and later the English Bar. As a barrister on the Connaught circuit from 1826 to 1832, Plunkett was credited by Daniel O’Connell for his contribution to the success of the Whigs regarding the general election in 1830.[2] As a result of this, he was rewarded the position of solicitor-general of NSW. Plunkett arrived in Sydney aboard the Southworth in June 1832 with his wife and sister and four female servants.

John Hubert Plunkett (1802-1869). Source: Australian Dictionary of Biography

From 1 August to 5 November 1833, Plunkett appeared on behalf of the NSW attorney-general, Kilkenny-born, John Kinchela (c.1774-1845), during the criminal session, leading ninety-one cases and obtaining sixty-four convictions. Due to the overwhelming duties placed upon Plunkett as solicitor-general, he drew attention from the Secretary of State asking for an increase in his salary. Unsuccessful with his request, Plunkett was however complimented in a reply stating he has ‘acquiesced in performing’ the extra duties he has carried out.[3] In February 1836, Kinchela retired and Plunkett was appointed to the position of attorney-general. It was in this position that Plunkett made significant changes to legal defects of the legislation, which established the equality of all men before the law in NSW.[4] His involvement in the Myall Creek massacre 1838 attempted to give the same protection, to the same degree, to Aboriginals in Australia. It was this historic trial that Plunkett became best known for in Australia.

Conflict between settlers and natives was an ongoing struggle in the Australian colonies during the nineteenth century, with many attacks against Aborigines happening both before and after the Myall Creek massacre in 1838. Up to two years prior to the massacre, a significant amount of conflict and violence had taken place in NSW due to squatters and convicts moving out into the Aborigines’ land.[5] With numerous clashes occurring between the settlers and Aboriginals, the climate among the colonial public was one of fear and anger. Aborigines were presented to the public through the press as cannibals and inhuman, with the Sunday Gazette stating: ‘If these men are benighted enlighten them, by all means, with a flash of musquetry and roar of cannon’.[6]

The massacre and subsequent trial

The Myall Creek massacre took place on 10 June 1838 near Inverell in Northern New South Wales. It resulted in the deaths of approximately thirty or forty of the Wirrayaraay and Gamilaroi peoples and was carried out by a group of European settlers, one of which was Irish. Those massacred had reportedly been living ‘in perfect tranquillity’ between several stations that were located on the creek.[7] They were said to have befriended the overseers that were located at Dangar’s station.[8] The reasoning behind their massacre is something that has never been confirmed. However, it has been suggested that many of the perpetrators came from families that had found their livestock being speared months/years prior; although these perpetrators probably knew that the Aborigines that were targeted would have had no involvement with this.[9] The Aborigines were said to have been tied up, ordered to walk to a location some distance away and then subsequently murdered by the group of men. All of the group were said to have been murdered aside from one woman and four or five children. It was also reported that the convicts searched the bush for the remainder of the tribe, and due to these other members never being heard from, it was concluded that they were also murdered.[10] Subsequently, the police were not able to charge the perpetrators for all the crimes as they could only prove with their investigation that about twenty-eight individuals had been murdered.

It is difficult for the historian to generalise Irish involvement in Aboriginal violence. This is exemplified by those concerned with the Myall Creek massacre and its aftermath; this massacre showed that personal outlook, involvement and response to such conflict depended solely on the individual. Following the massacre, an investigation was ordered to be carried out which resulted in ten men being brought to Sydney for prosecution; one of the policemen that captured them, Edward Denny Day, was also Irish.[11] Irish immigrants were thus among perpetrators, policemen and persecutors – and John Hubert Plunkett spearheaded the case against the accused. Plunkett, as attorney-general, was reportedly feared by criminals. Aubrey Halloran stated that ‘Once in his grip they trembled, for he was not to be put aside from his path of duty by a critical public, or by false sentiment’.[12] This description of Plunkett is borne out by his participation in the Myall Creek massacre trial as the majority of the public were outraged by the men being taken to court for the murder of a group of Aborigines. The Sydney Morning Herald commented on the decision to prosecute the perpetrators in an particularly derogatory article titled ‘The Blacks’:

‘The whole gang of black animals are not worth the money the Colonists will have to pay for printing the silly documents.’[13]

The Sydney Morning Herald was not the only newspaper that backed the settlers but it did have a particular agenda. The editorial voice of the paper, Ward Stephens, was a squatter who accumulated, through numerous years, large runs in new frontiers in NSW. He was also a friend of a landowner who funded the defence of the Myall Creek massacre accused.[14] With newspapers being one of the most popular forms of spreading information it is undeniable that this played a significant role in shaping, or influencing, the colonial public’s outlook on the massacre, the trial and perceptions of Aborigines in general.

The men accused for the murder of one specific individual named ‘Daddy’ and the public rallied behind them despite the extent of the violence they partook in. Plunkett, despite the public outrage, sought to successfully prosecute the men for their crimes, persevering through the failure of the first trial to a successful retrial. Plunkett knew that the response from the public regarding the prosecution of the settlers could potentially affect the jurors’ decisions so he asked them at the beginning of the first trial:

‘Before going into the case, I must entreat you, gentlemen, to dismiss from your minds all impressions which may have been produced by what you may heard or read on the present subject’.

However, despite Plunkett’s efforts throughout the trial, they were found not guilty, after a deliberation of forty-five minutes, due to insufficient evidence based on the fact that none of the bodies could be identified as the man known as ‘Daddy’. It is noteworthy that the victims had been burned and the perpetrators had removed a significant amount of the remains from the site before investigations took place, which meant the site that was tampered with before evidence could be retrieved.[15]

Despite this lack of evidence, it is clear that a high level of bias against the Aborigines in the decision-making in this case. Later, one of the jurors expressed their disgust to The Australian stating: ‘I look on the blacks as a set of monkeys and the sooner they are exterminated from the face of the earth, the better. I knew the men were guilty of murder but I would never see a white man hanged for killing a black’.[16] Plunkett, a lawyer who sought to prosecute the settlers for their crimes against the Aborigines despite the support the settlers had gained from the public, requested a retrial against the settlers that partook in the violence against the Aborigines.

Retrial and aftermath

Plunkett did not fear the backlash that would be caused by the retrial and returned to court with a new case against seven of the accused. Throughout the analysis of the newspapers mentioned here that documented the trial, the voices of the minority who favoured the side of the murdered Aborigines were heavily outweighed by the opinions of the majority against the Aborigines. It is noteworthy that the backgrounds of the settlers, whether Irish, Scottish or English, appears to have had no real bearing on what side they favoured regarding the conflict with the Aborigines. Once again, Plunkett showcased this dynamic within NSW; he was trying to prosecute an Irishman among those accused of participating in the murders, something he was successful in doing with the second trial.

The second trial had a fresh jury who were satisfied with the evidence presented by Plunkett, and the seven accused were found guilty and sentenced to death.[17] As expected, this caused outcry among the colonial public. The popular opinion was that the prosecuted should not be executed for the killing of Aborigines. Indeed, it was later reported that the seven individuals defended their actions after their conviction and before their death by claiming ‘they were not aware that in destroying the black natives they were violating the law’.[18] Attempts were made by members of the public to revoke the sentence given to the convicted, but they exasperated all possible forms and the individuals were hung in December 1838. What makes the Myall Creek massacre, and the court cases surrounding it, so significant regarding Australia’s history is that it was the first massacre on the colonial frontier that resulted in non-indigenous murderers of Aboriginal people being convicted for their crimes. However, according to Peter Garrett, ‘it was the first and last time the Colonial Administration intervened to ensure the laws of the colony were applied equally to Aboriginal people and settlers involved in frontier killings’.[19]

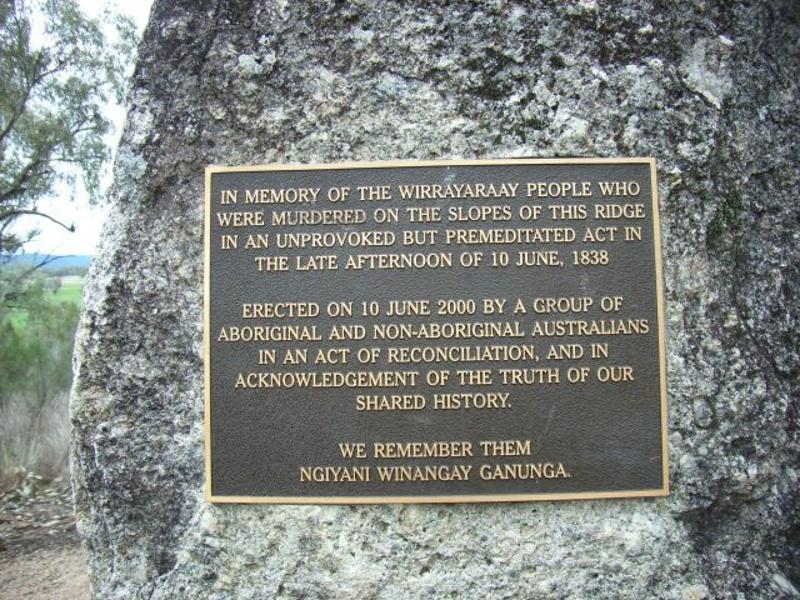

Photograph by Tracy Appel of bronze plaque commemorating the Myall Creek massacre 1838. Copyrighted to Heritage Office NSW. Source: NSW Government Land and Property Information: Heritage sites and assets

What can be seen then as a successful trial on Plunkett’s part only caused even more problems of violence against Aborigines. The mass protest that was a result of the execution of the convicted settlers, resulted in the colonial administration avoiding getting involved in any violence involving Aborigines.[20] The Myall Creek massacre highlighted many of the issues in the administrative, legal and judicial systems in colonial Australia, especially regarding Aboriginal and settler conflicts highlighting the hatred that was felt by many colonists towards the Aborigines. Furthermore, the involvement of a variety of individuals on both sides indicated that where individuals originated from did not necessarily impact the mindset they had in colonial Australia. English, Irish, Scottish or elsewhere, the mindsets varied among them all and Plunkett highlighted this. In the face of popular opinion, he saw the perpetrators involved in the Myall Creek massacre as lawbreakers that they needed to be punished regardless of origin. He persevered despite the disagreements with his decision and was successful. However, this attempt by one Irish immigrant at fairness in serving justice in colonial New South Wales was short-lived as violence by colonists against Aborigines was not stopped – it only became secretive.

Furthermore, scholars like Jane Lydon have asserted that the execution of colonists for the Myall Creek massacre ‘hindered colonial officials pursuing similar crimes against Aboriginal people for decades afterwards, because they were unsure of the legal outcome and the public backlash’.[21] It can be suggested though that Plunkett’s success in prosecuting colonists in the Myall Creek massacre retrial was a stepping stone of sorts, resulting by 2008 in its recognition as a pivotal moment in Australia’s history and, ultimately, the creation of a memorial and the addition of the site to the National Heritage List.[22]

REFERENCES

Transcripts of the two famous Myall Creek massacre cases (derived from contemporary newspaper reports) are available at: Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788-1899, Law Division, Macquarie University http://www.law.mq.edu.au/research/colonial_case_law/nsw/cases/myall_creek/

[1] Aubrey Halloran, ‘Some early legal celebrities’ Royal Australian Historical Society: Journal and Proceedings, 10.6 (1924), pp 328-29, National Library of Australia (http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-600995280) (accessed 2 Apr. 2018)

[2] T. L. Suttor, ‘Plunkett, John Hubert (1802–1869)’, (1967), Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB), Australian National University (ANU) (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/plunkett-john-hubert-2556/text3483) (accessed 2 Apr. 2018)

[3] Halloran, ‘Some early legal celebrities’, pp 330-31.

[4] Suttor, ‘Plunkett, John Hubert (1802–1869)’.

[5] Jane Lydon, ‘Anti-slavery in Australia: picturing the 1838 Myall Creek massacre’ in History Compass, 15.5 (2017), pp 2-3.

[6] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 20 Oct. 1836.

[7] The Farmer and Settler, 31 Oct. 1911, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118012414).

[8] The Canberra Times, 27 Oct. 1987, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122110580).

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser, 15 Nov. 1911, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article215775751).

[11] Ben W. Champion, ‘Day, Edward Denny (1801–1876)’, (1966), ADB, ANU (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/day-edward-denny-1970/text2381) (accessed 2 Apr. 2018)

[12] Halloran, ‘Some early legal celebrities’, p.332.

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 Oct. 1838, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12856847).

[14] Colonist, 15 Dec. 1838, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article31722156).

[15] ‘R. v. Kilmeister (No. 1) [1838] NSWSupC 105’, Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788-1899, Division of Law, Macquarie University (http://www.law.mq.edu.au/research/colonial_case_law/nsw/cases/case_index/1838/r_v_kilmeister1/#bn1); Sydney Gazette, 20 November 1838.

[16] The Australian, 8 Dec. 1838, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36861194).

[17] Halloran, ‘Some early legal celebrities’, p.333.

[18] The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser, 15 Nov. 1911.

[19] Peter Garrett M.P., Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts, ‘Media release: Myall Creek Massacre recognised 170 years on’, PG /84, 7 June 2008 (https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/fefa8cc8-63df-468c-944f-37db50561799/files/mr20080607.pdf) (accessed 2 Apr. 2018)

[20] Garrett, ‘Media release: Myall Creek Massacre recognised 170 years on’, p.1.

[21] Lydon, ‘Anti-slavery in Australia: picturing the 1838 Myall Creek Massacre’, p.8.

[22] ‘Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: INCLUSION OF A PLACE IN THE NATIONAL HERITAGE LIST: Myall Creek Massacre and Memorial Site’, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No. S116, 7 June 2008, p.2, (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/fefa8cc8-63df-468c-944f-37db50561799/files/10586901.pdf) (accessed 2 Apr. 2018)