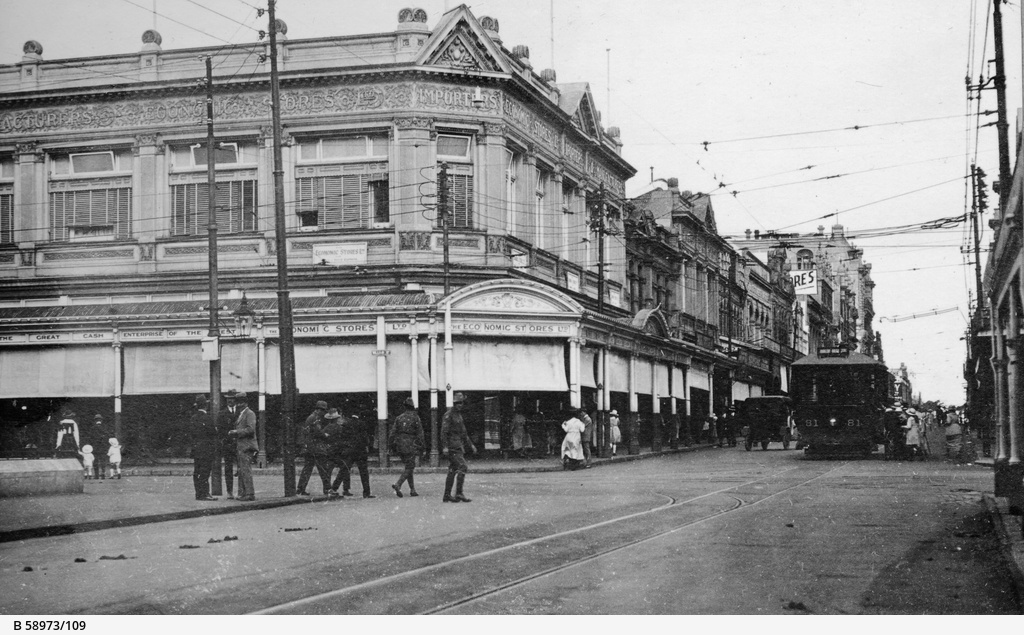

A Perth street corner circa 1918. Source: State Library of South Australia

The Irish in Perth faced a struggle during the years of the First World War. Although many Irish-Australians from Perth enlisted in the war, there was still some bias towards them after the Rising of 1916. The Irish in Perth were then obliged to assert their loyalty to Australia, while still maintaining their Irish identity. It is contended here that the Irish in Perth were as proud of their Irish heritage as they were loyal to Australia, rather than only one or the other.

An event that was intrinsically linked to the identity of Irish-Australians in Perth was its St. Patrick’s Day Parade. St. Patrick’s Day was important to both Irish and Catholic communities in Australia as it was both a civic and religious holiday. By 1914, it had been Ireland’s national holiday for only 11 years, yet it was celebrated as a Catholic and Protestant feast day for many years before this. St. Patrick’s Day celebrations had been taking place annually in Perth since at least the 1850s. A noteworthy figure involved in these events was Walter Dwyer, an Irish-born man who was a leading organiser of Perth’s St. Patrick’s Day celebrations every year. His role in these parades and his impact on Irish identity in Perth during World War I will be examined here using newspaper reports from between about 1914 and 1920 which reveal the nature of these parades and reactions to them, as well as information about Dwyer. These primary sources are essential in exploring Irish identity during the wartime years in Perth; a variety of different newspapers have been examined for some measure of objectivity.

Work by prominent historians like Malcolm Campbell, Ian Chambers and Patrick O’Farrell will be referenced to contextualise the information found in primary sources. Chambers, for example, contends that the Irish in Perth considered themselves Australian first and viewed their Irish identity as secondary.[1] Although this discusses the years leading up to 1914, it is relevant as is discusses the same community. His conclusion is not unchallenged, however. Campbell asserts that Irish-Australians were outwardly loyal to Australia first.[2] However, he suggests that Australia’s links to Britain may have made it difficult for Irish people to express what they really thought. On the other hand, O’Farrell asserts that the question of loyalty to Ireland was more complicated than this and also depended on a whether a person remembered Ireland or had just heard about it.[3] Contrary to these historians, it is argued here that the Irish in Perth were loyal to both Australia and Ireland

St. Patrick’s Day during the First World War

The First World War was significant for Australia. Not only did numerous men enlist to fight, but many women also worked as nurses. It has been confirmed that at least 6,000 of those who enlisted in Australia were Irish.[4] Over 300 Irish people enlisted in the city of Perth.[5] The focus here however is on the Irish community who remained in Perth during wartime.

Matters in Ireland during the First World War undoubtedly impacted the Irish in Australia. In 1914, the Home Rule movement in Ireland to gain partial independence from the United Kingdom had gained momentum. Many Irish in Australia were also campaigning for ‘Home Rule’ and were certain that it would be achieved by the end of the year. Melbourne’s Archbishop Carr conveyed this, stating to one reporter in the lead-up to the city’s parade 1914 that those involved in St. Patrick’s Day events ‘could tell their children that they took part … in the year that Ireland obtained Home Rule’.[6] This also shows how closely St. Patrick’s Day parades in Australia were tied to Irish politics.

In Perth, the 1914 St. Patrick’s Day parade was described as ‘a spectacle of exceptional splendour’ in the Western Mail which acknowledged that it was not a public holiday, but the celebrations were still a success. According to this newspaper, the crowds at the 1914 parade were bigger than ever before and the city trams simply had to ‘yield to the popularity of St. Patrick’. It went on to describe details of the parade, including the involvement of a band, the local Catholic Archbishop, and notably, the Home Rule banners carried by marchers; at this point it clearly expressed an Irishness that was Catholic and nationalist.[7]

With the outbreak of the First World War later in 1914, Home Rule became much less likely.[8] Despite this, many of the Irish in Australia were still hopeful about its prospects. By 1916, Perth’s St. Patrick’s Day celebrations were described in a column in the Daily News as less spectacular than events of earlier years, as a mark of respect for all who were then fighting in WWI.[9] This column also stated that St. Patrick’s Day festivities would be expected to return to normal at the end of the war currently taking place. At this point, it seemed that the Irish in Perth were still welcome to celebrate their heritage without it being deemed disrespectful to the British and Australian war efforts. Yet with the events of the 1916 Easter Rising only a few weeks away, this was about to change.

Tension in Perth, 1916

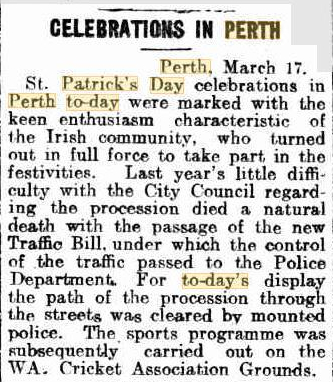

‘Celebrations in Perth’, Kalgoorlie Miner, 18 March 1920. Source: National Library of Australia’s Trove

The Rising had a profound impact on the lives of the Irish in Australia, despite taking place far away across the world. A report in the Kalgoorlie Western Argus from 23 May 1916 portrays the betrayal that many Australians felt; it described the Rising as ‘the most deplorable, disappointing and perplexing event of the war’ as well as ‘tragic and disloyal’. It stated that most members of the Irish Volunteers were ‘shirkers’ who only joined this force to avoid fighting in WWI; they were no more than cowards disguised as patriots. The leaders of the Rising were also condemned – Countess Markievicz was described as a ‘hysterical woman’ and Sir Roger Casement as ‘a criminal lunatic’. Regardless of the anger that the author clearly felt, they were careful not to blame all Irish people and ended their piece by declaring that it only a minority had caused such trouble, and ‘at least forty-nine out of every fifty of the people of Ireland have been true’.[10]

An attitude of wariness towards the Irish soon became widespread in Australia. The above condemnation was only one of many that were published. After the rebellion, leaders of several Irish groups in Australia were quick to denounce the events of 1916 and pledge their loyalty to Australia.[11] Catholic clergy did the same. This was to be expected of the Catholic Hierarchy, who were staunchly anti-violence. While many Irish nationalist groups in Australia had been previously supportive of the peaceful Home Rule movement, they too would not support a militant uprising against the Crown.

The Rising and its aftermath certainly created tension for the Irish in Australia. By March of 1917, this strain remained. Yet St Patrick’s Day organisers decided to organise an enormous celebration. A piece published in The W.A. Record on 24 Mar 1917 described the event in detail over two pages. As well as describing the music and parade, it printed an entire speech that was given on the day.[12] It also featured a photograph of the orator, an Irishman named Walter Dwyer.

Walter Dwyer (1875–1950)

Walter Dwyer was born in 1875 in Tipperary, Ireland, and was educated there until the age of sixteen. He then migrated to Australia where he became a teacher in Melbourne, occasionally teaching students who were older than him.[13] He moved to Western Australia in 1895, working as a clerk while he studied to become a lawyer. He eventually finished his studies and settled in Perth where he practiced from 1910 onwards. It seems that he became involved with the Irish community in Perth, and particularly the organising of the city’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, around this time.

Mr Walter Dwyer LL.B., The W.A. Record, 24 March 1917. Source: National Library of Australia’s Trove

Dwyer’s 1917 speech was rousing. In it, he described the nature of the Irish people and their history. He described St. Patrick’s Day as a day of religious celebration as well as of political and national pride. He outlined Ireland’s struggles and attributed them to its lack of political independence. His speech was a call for independence, yet at no point did it call for violence; Dwyer ended his speech by reminding the crowd that Irish people should be peaceful, and he hoped that ‘sympathy and understanding’ would be undertaken by the British with regards to Ireland. This speech was not the only evidence of emboldened Irish pride in Perth and the Irish community in the city seemed unafraid to proclaim their devotion to Ireland. In one December 1917 article in the The W.A. Record, journalists and politicians in Australia were accused of misrepresenting Irish people, describing an ‘anti-Irish campaign’.[14] The author then declared that the Irish in Western Australia had nothing to be ashamed of and were just as Australian as their neighbours.

By 1919, although the First World War had ended, unease between the Irish community in Perth and others in the city remained. At this point, 17 March had been Ireland’s national holiday since 1903, yet it was not officially recognised in Australia. In February 1919, Perth’s City Council ruled that they would allow for a St. Patrick’s Day parade only if organisers agreed that an Australian flag and a Union Jack flag would be carried at the beginning of the parade. They also wanted permission to disallow anything in the parade that they found offensive.[15] Organisers refused this and so, instead, Perth’s 1919 St. Patrick’s Day parade was officially banned. Nevertheless, it went ahead illegally, and although prohibited, was one of the largest in the history of the city.[16] Evidently, the Irish in Perth were growing more insistent about celebrating the national holiday of Ireland.

Walter Dwyer led the 1919 procession and was arrested and fined for doing so.[17] It seems that the authorities in Perth were attempting to make an example out of Dwyer – instead they made him into something of a hero. In July 1919, a rally was arranged by the Irish community in Perth to honour Dwyer. As well as being a demonstration of respect for Dwyer and his actions, it was also a protest against Perth City Council’s decision to ‘restrict the rights of Catholics and Irishmen to walk … on the Feast Day of Saint Patrick’.[18] Dwyer spoke once more at this gathering, discussing the restrictions that the City Council wanted to impose on St. Patrick’s Day parades, and dismissing them all, something met with cheers from the crowd.

In 1920, the struggles between the Perth City Council and the organisers of St. Patrick’s Day festivities finally ended. A new bill was passed giving the right to the Perth Police Department to prohibit or permit parades.[19] This department ruled to allow the St. Patrick’s Day parade without restrictions in 1920, and according to newspaper reports, it was a great success. Following the legalisation of the parades, the Irish community in Perth no longer had to campaign to celebrate their heritage; they were free to embrace both their Irish and Australian identities equally. In fact, Walter Dwyer went on to have a long career as a state judge and was even knighted in 1949. He has been celebrated as a great figure by Australians from all walks of life.

The Irish community in Perth faced a dilemma during wartime years with regards to their identity. These events show us what Perth was like for the Irish in wartime Australia. During the years of WWI, it became a tumultuous place. The Irish living there had to proclaim their right to live freely not only as Australians, but as Irish-Australians. It is clear from the above that in wartime years, the Irish community in Perth celebrated their identity as both Irish and Australian; not one of these alone.

REFERENCES

[1] Ian Chambers, ‘“I’m an Australian and speak as such”: the Perth Catholic Irish community’s responses to events in Ireland, 1900-1914’, in Bob Reece (ed), The Irish in Western Australia (2000).

[2] Malcolm Campbell, ‘Emigrant responses to war and revolution, 1914-21: Irish opinion in the United States and Australia’, Irish Historical Studies, 32:125 (2000), p. 83.

[3] Patrick J. O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia (Kensington, 1986), p. 198.

[4] ‘Irish Anzacs Database’, University of New South Wales, Sydney (hereafter UNSW website) (https://hal.arts.unsw.edu.au/about-us/community-engagement/irish-studies/irish-anzacs-database/) (2 April 2018)

[5] Search: Perth, ‘Irish Anzacs Database’, UNSW website (https://repository.arts.unsw.edu.au/primo-explore/search?query=any,contains,%22irish%20anzacs%20project%22&tab=iap&search_scope=IAP&sortby=rank&vid=FASS&mfacet=local26,include,Perth,1&lang=en_US) (2 April 2018)

[6] Mike Cronin and Daryl Adair, The wearing of the green: a history of St Patrick’s Day (London, 2002), p. 113

[7] Western Mail, 20 Mar 1914, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/37967580?searchTerm=st%20patrick%27s%20day%20perth&searchLimits=dateFrom=1914-01-01|||dateTo=1918-12-31|||l-advstate=Western+Australia)

[8] Cronin and Adair, The wearing of the green, p. 113

[9] The Daily News, 17 March 1916, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/80890021?searchTerm=irish%20perth%20parade&searchLimits=l-state=Western+Australia|||l-decade=191)

[10] Kalgoorlie Western Argus, 23 May 1916, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/33605081?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Fdate%2F1916%2F05%2F23%2Ftitle%2F73%2Fpage%2F4193242%2Farticle%2F33605081)

[11] Cronin and Adair, The wearing of the green, p. 114

[12] The W.A. Record, 24 Mar 1917, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/212594236?searchTerm=irish%20ignored%20perth&searchLimits=dateFrom=1914-01-01|||dateTo=1918-12-31|||l-advstate=Western+Australia)

[13] E.A. Dunphy, ‘Dwyer, Sir Walter (1875–1950)’ in B. Nairn (ed.), Australian Dictionary of Biography, 8 (1981), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dwyer-sir-walter-6067/text10383) (2 April 2018)

[14] The W.A. Record, 8 Dec 1917, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/212682908?searchTerm=perth%20irish%20great%20war&searchLimits=dateFrom=1914-01-01|||dateTo=1924-12-31)

[15] Barrier Miner, 28 Feb 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/45474556?searchTerm=perth%20irish&searchLimits=exactPhrase|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom=1914-01-01|||dateTo=1924-12-31|||sortby)

[16] Geraldton Guardian, 18 Mar 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/66508925?searchTerm=perth%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y)

[17] Dunphy, ‘Dwyer, Sir Walter (1875–1950)’

[18] Southern Cross, 25 Jul 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/167789589?searchTerm=perth%20irish&searchLimits=exactPhrase|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom=1914-01-01|||dateTo=1924-12-31|||sortby)

[19] Kalgoorlie Miner, 18 Mar 1920, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/93167956?searchTerm=%22patrick%27s%20day%22%20perth&searchLimits=l-advstate=Western+Australia|||dateTo=1922-12-31|||dateFrom=1920-01-01|||sortby=dateAsc)