SS Great Britain leaving Prince’s Pier, Liverpool, for Australia, 1852. Source: Australian National Maritime Museum

Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century were not unaccustomed to discrimination in their new homes in America and Britain. While they were provided opportunities that could not be found in Ireland, they were not always welcomed and so reputations were gained on both sides. The Irish garnered a reputation for being loud, drunk and lazy, while Irish immigrants themselves began to feel victimised and often contributed to their own poor treatment. In colonial Australia, while the treatment was not as pronounced as it was in America and Britain, it was certainly present.[1] A certain amount of this discrimination was sectarian in nature but some of the primary sources available to us from the period suggest that it was based just as heavily on cultural identities and reputations, specifically the idea that the Irish were a people prone to violence and nationalistic extremism.

Nineteenth-century immigration schemes

To a certain extent, anti-Irish sentiment had existed since the penal beginning of the Australian colonies, with those prejudiced attitudes having travelled with the settlers from their home countries. This institutionalised prejudice however came to light much more clearly towards the middle of the nineteenth-century, when a number of immigration schemes came into play in order to increase the population.

One of the key schemes involved the migration of Irish female orphans from Ireland to fill the rapidly growing gender gap within the population.[2] However with the large number of female migrants from distinctly disadvantaged backgrounds, they amassed a poor reputation that clung to the Irish migrants in general. South Australia, due to the late date of its establishment as a colony and low population as a result, received more migrants from the scheme than perhaps any other colony and, as such, much of the outrage was centred there, where it was described as: ‘a fraud upon the colonists, but as fraught with the most serious evils to the legitimate emigration scheme’.[3] Among the criticisms of the women as they arrived were the intimations that they were:

‘Too useless for servants, and too ugly for outcasts […] a more useless or a more depraved set were not to be found,’ while ‘their personal appearance rendered them ineligible to fill the ranks of prostitution!’[4]

The back-lash to the schemes, despite their obvious benefits, was such that meetings were organised in order ensure that the Irish character was not ‘belied’. In one example of these gatherings, covered by the Geelong Advertiser in 1850 a meeting of up to 500 people is described passionately, referring those that spoke against the Irish migrants to ‘the descendants of the snakes banished from Ireland by St. Patrick’. Geelong was at this point, a small port town in Victoria. The meeting was composed of members of the Society of St. Patrick, a club that existed to celebrate Irish culture and heritage among the diaspora, and so the group has a clear cultural bias. The language used by Mr. Finn, the vice-president of the society, in a speech defending the character of these Irish orphans was nationalistic, as he called to mind memories of past perceived transgressions against the Irish people. He used phrases like ‘to hell or to Connaught’, evincing feelings of victimisation among the gathered Irish immigrants that had been brought to light by the accusations against the girls.[5] Of course, the controversy around the Irish orphans contributed to a larger problem of Irish migrants in Australia where they were seen as poorer, and less educated than their contemporaries.

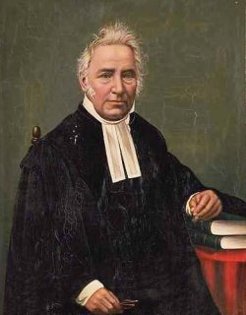

John Dunmore Lang, artist unknown, 1888. Source: Australian Dictionary of Biography

This was alluded to by John Dunmore Lang in his writings. Lang was a Presbyterian minister interested mainly in the education and morality of the new colonies and was one of the loudest voices in opposing the arrival of Irish immigrants.[6] In the text he discussed the time as a penal colony and singled out the Irish convicts as being ‘no scholars’ in comparison to the others, a fact which in his opinion contributed to the failure of the earliest colonisation.[7] However, it is also true that in the first half of the nineteenth-century it was a ‘criminal offence to educate an Irish child’, and yet, as that same child reached adulthood, he would be ‘jeered at’ for his lack of education.[8] This reputation, as ill-behaved and poorly educated, provided a basis for discrimination against the Irish diaspora, both in terms of migration and employment and yet was almost enforced by certain policies within the colonies. The arrival of Irish orphans was met with considerable outrage and further served to lead to discrimination on the basis of Irish migrants being unskilled, uneducated, and in the case of some, prone to immorality. As some of the girls turned to prostitution to survive, the rest had to suffer the prejudice and attempts to stop Irish migration to the colonies.

Existing prejudices and ‘Fenianism’

A certain amount of the anti-Irish feeling that emerged in nineteenth century Australia came from the political atmosphere back in Ireland. The eighteenth century closed with the rebellion of the United Irishmen in 1798 and these republican attitudes would endure in some circles for much of the nineteenth century. As Ireland rebelled more vigorously against English rule and agitated for land reform and home rule, protests often grew forceful and contributed to the reputation of the Irish people as barbarous and violent. The Castle Hill convict rebellion of 1804 was a direct result of the transfer of Irish nationalism and anti-colonial feelings. John Dunmore Lang described the rebellion perpetrated by those convicts that had participated in the Irish rebellion of 1798 as the only significant act of insurrection against the ruling parties of the Australian colonies in their history.[13]

Incidents like this perpetuated a certain stereotype of the Irish settlers in the Australian colonies that would endure among critics and provide a supposed basis for discrimination. However, even in instances where there was no direct action within Australia itself, tensions between Irish nationalists and British rule transferred because of the press.

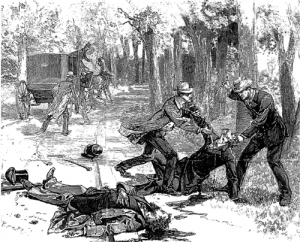

The Phoenix Park Murders as depicted in Le Monde 1882. Source: History Ireland

In 1882, for example, following the murders of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Henry Burke in Phoenix Park, many newspapers across the states of Australia began to report on the riots and scandals that were unfolding across the British Isles.[14] As late as the 1890s, the incident was still being reported on and the supposed connections between the assassinations and the Irish Parliamentary Party were being explored.[15] This perpetuation of news stories about Irish violence and the ensuing anti-Irish rallies helped to provide a basis for the same behaviour in colonial Australia despite the fact that only the small minority of the Irish diaspora that would have supported Fenian extremism.

While there was no initial institutional prejudice or discrimination – unlike in America – certain acts or behaviours by Irish settlers contributed to the shared opinion of them as violent and extreme in their political beliefs. One such incident occurred in 1868 when an Irishman named Henry O’Farrell, who was described as a ‘Fenian’, attempted to assassinate the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Albert, during his royal visit to Sydney.[9] The fact that the Irishman chose colonial Australia for a crime that was nationalistic in nature was behind much of the anti-Irish outrage that followed, as expressed in the press. The Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser stated: ‘it was peculiarly wicked to do this act in Australia. Prince Alfred was a guest of the colonies’. Despite the prince having no influence over Irish affairs and conditions, when asked about his reason for crime, O’Farrell responded: ‘I did not shoot the Duke of Edinburgh to take his gold, or to revenge private quarrel; I shot him for the sake of my country’.[10]

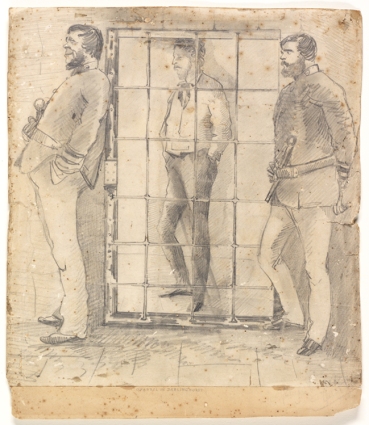

Henry James O’Farrell in Darlinghurst Jail by Francis Charles Needham, Viscount Newry, 1868. Source: Dictionary of Sydney

Reaction to the assassination attempt varied but many newspaper articles referred to his Farrell’s ‘Irishness’ as an indicator for his behaviour, with the Mercury in Hobart, Tasmania, claiming: ‘the deed was dictated only by that dark malice and stupidity which produces the kind of murders for which Ireland is notorious, and which will keep civilisation and commerce from that island’.[11] In a short book circulated during the Prince’s recovery, Samuel Cozens pointed to the incident as a warning: ‘This dire deed has shown us how possible it is even for a small faction to animate a wicked mind to a dreadful vengeance’. Once again, the text pointed to growing Irish extremism among Fenians, but acknowledged that they were in a minority among the Irish diaspora as a whole in colonial Australia.[12]

These occurrences were something of a by-product of the behaviour of those elsewhere, with the reputation of the Irish as violently minded and uneducated was passed, both from existing prejudices among other migrants, and through the press. This reputation was furthered by the actions of a select few, such as the convicts who participated in the Castle Hill uprising and so-called Fenians such as Henry James O’Farrell. These men committed violent acts in Australia for the sake of their homelands, with little consequence for their own ends but instead merely confirmed for many that the Irish were prone to violence.

The Anti-Irish Irishman

Part of the issue that other settlers found with the Irish immigrants was their tendency to band together as Irish communities within the colonies. This was much more prevalent in America, where they were often ghettoised, whereas across the Australian colonies they tended to diffuse more evenly, geographically speaking.[16] However there were instances of towns that were largely Irish, and this gave those with public platforms and influence like Dunmore Lang cause to question them. In his visit to the countryside of New South Wales in 1862 he came across the town of Boorowa, which, he complained, ‘might almost be supposed to be a veritable slice of the county Tipperary’. He took issue with the ‘Irish-ness’ of the town, claiming that it was ‘unhealthy’ for any one town to be of ‘so one-sided a character’.[17] Despite, or perhaps because of, these Irish communities within Australia, anti-Irish sentiment was not just limited to settlers from England and elsewhere – it also came from the Irish themselves.

A common feature of Australian newspapers, particularly during the 1880s and 1890 were articles with titles that varied on the notion of ‘The Anti-Irish Irishman’. One such example in 1896 laments the loss of culture within the diaspora. The article was originally printed in the Catholic Press, a paper with obvious ideological ties, and spoke of ‘a small group of worthless Irish Catholics in this colony whose one aim in life is to crawl into some snug, fat position by ignoring as much as possible their nationality and their faith.’[18] A poem by Hugh Harkan titled ‘The Anti-Irish Irishman’, originally published in The spirit of the nation (1845), Thomas Davis’ edited volume of ballads and songs, was republished in several newspapers in Australia between the 1890s and the early 1900s. The poem expressed outrage at those who threw off their Irish identity in favour of another: in this case, an ‘Australian’ identity.[19] It refers to anyone who did this as ‘the Norman’s sneaking slave’ and a ‘treacherous stealthy knave/ That bends beneath his country’s ban’.[20]

For ages rapine ru’ed our plains.

And slaughter raised ‘his red right hand,’

And virgins shrieked, and roof-trees’ blazed,

And desolation swept the land!

And who would not those ills arrest,

Or aid the patriotic plan

To burst his country’s galling chains?

The anti-Irish Irishman.

– Hugh Harkan, ‘The Anti-Irish Irishman’, 1902

Ironically, these divisions within the Irish diaspora itself contributed greatly to opinions of the Irish as an argumentative people, while their tendency to focus themselves in communities left them open to criticism from those like Dunmore Lang.

The Irish in Australia can be said to have been treated relatively fairly, especially when compared with the Irish in other locations like America. Some of the prejudices formed against them existed prior to their arrival with the first wave of convicts in the late eighteenth century, leading to a reputation to be shaken off before many Irish immigrants had even arrived. The enduring image of the Irish immigrant as lazy, violent, and drunk was prevalent within the Irish colonies and was bolstered by the actions of men like Henry James O’Farrell. These men called themselves patriots or ‘Fenians’ and committed violent acts on Australian soil in the name of their homeland. These isolated acts only damaged Irish reputations further thought there was acknowledgment that this violence was perpetuated by a small group of individuals rather than the entire diaspora. Ultimately, a certain amount of anti-Irish sentiment came from the Irish themselves, as they took issue with each other for internal issues, such as cultural identities and religion and consequently presented a view of a quarrelling and divided community that could be easily judged and discriminated against.

REFERENCES

[1] Malcolm Campbell, ‘The other immigrants: comparing the Irish in Australia and the United States’ in Journal of American Ethnic History, 14.3 (1995), p. 4.

[2]Eric Richards, ‘Irish Life and Progress in Colonial South Australia’ in Irish Historical Studies, 27.107 (1991), p. 223.

[3] South Australian Register, 25 October 1848, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/48726139?searchTerm=irish%20orphan%20prostitution&searchLimits=l-availability=y) (28 March 2017).

[4] Melbourne Daily News, 22 April 1850, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/226320985?searchTerm=irish%20orphan%20prostitution&searchLimits=l-availability=y) (28 March 2017).

[5] Geelong Advertiser, 13 May 1850, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/93137443?searchTerm=irish%20orphan%20prostitution&searchLimits=l-availability=y) (28 March 2017).

[6] Campbell, ‘Comparing the Irish in Australia and the United States’, p. 4.

[7] John Dunmore Lang, An historical and statistical account of New South Wales: both as a penal settlement and as a British colony, (London, 1837), p. 61.

[8] Bendigo Independent, 9 December 1897, National Library of Australia’s Trove http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/183753093?searchTerm=anti%20irish%20gold%20convict&searchLimits=l-availability=y (28 March 2017).

[9] The Mercury, 4 July 1868, National Library of Australia’s Trove http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8853185?searchTerm=assassination%20attempt%20prince%20alfred%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y, (8 March 2017).

[10] Dalby Herald and Western Queensland advertiser, 21 March 1868, National Library of Australia’s Trove http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/215450179?searchTerm=prince%20alfred%20assassination%20irish%20wicked&searchLimits=y. (28 March 2017).

[11] The Mercury, 4 July 1868, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8853185?searchTerm=assassination%20attempt%20prince%20alfred%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y) (28 March 2017).

[12] Samuel Cozens, The attempted assassination of His Royal Highness, Prince Alfred: a tribute of affectionate loyalty to England’s matchless queen, (Launceston, 1868), p. 9, (http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/18869108?q=assassination+attempt+prince+irish&l-availability=y&c=book&versionId=22150296) (28 March 2017).

[13] Dunmore Lang, An historical and statistical account of New South Wales, p. 88.

[14] Australian Town and Country Journal, 13 May 1882, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/70968980?searchTerm=anti%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y|||l-australian=y) (28 March 2017).

[15] Daily Telegraph, 28 May 1894, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/153549751?searchTerm=phoenix%20park%20murders%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y) (28 March 2017).

[16] Oliver MacDonagh, quoted in Malcolm Campbell, ‘Ireland’s furthest shores: Irish immigrant settlement in nineteenth-century California and Eastern Australia’ in Pacific Historical Review, 71.1 (2002), p. 65.

[17] John Dunmore Lang, Notes of a trip to the westward and southward in the colony of New South Wales in the months of March and April 1862 (Sydney, 1862), p. 27.

[18] Southern Cross, 13 March 1896, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/166348923?searchTerm=anti%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y|||l-australian=y) (28 March 2017).

[19] Richards ‘Irish life and progress in Colonial South Australia’ , p. 233.

[20] Hugh Harkan in Catholic Press, 11 December 1902, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/104417288?searchTerm=anti%20irish&searchLimits=l-availability=y|||l-australian=y) (28 March 2017).

[21] Campbell, ‘Comparing the Irish in Australia and the United States’, p. 4.