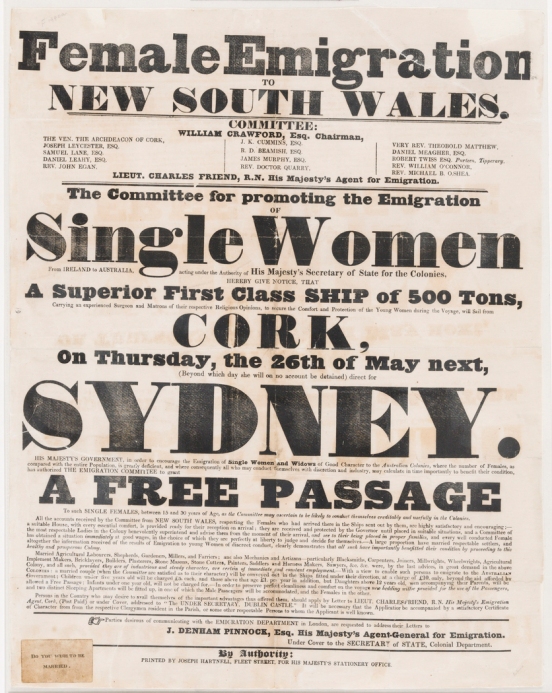

Poster advertising free female emigration to Australia prior to the ‘Earl Grey scheme’, c.1835. Source: State Library of New South Wales, [a6087008 / D 356/17/8], (Mitchell Library), accessed here at: Dictionary of Sydney

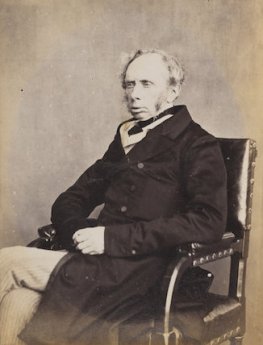

A female orphan scheme to transport girls from the workhouses of Ireland to Australia –known as the ‘Earl Grey Scheme’ – was devised by secretary of state for the colonies, Henry Grey, 3rd Earl Grey, during the Great Famine, 1845-52. Although Irish orphan girls had been transported to Australia in earlier in the nineteenth century, Grey’s scheme intended to would reduce the amount of girls in workhouses; but it would also benefit Australia as it would decrease the gender imbalance which had become problematic in the colonies.[1] Between 1848 and 1850, over 4,000 young teenage girls were transported from Irish workhouses to Australia to be prepared for domestic labour. For the Australian population, this would not just mean the arrival of 4,000 extra girls, but rather the arrival of additional Irish people. With many areas of Australia by this time settled by people of ‘respectable’ English and Scottish descent, the arrival of numerous poor, uneducated Irish was unnerving for many. [2]

Although Irish orphan girls had been transported to Australia in earlier in the nineteenth century, the Earl Grey scheme which began in the midst of the Irish Famine came to a cessation in 1850. It is apparent that although there was a high level of public optimism for the scheme demonstrated in the printed press, the scheme ultimately failed and dismay was expressed by newspapers in New South Wales and South Australia. Like today, these media outlets had different agendas which contributed to whether they portrayed the girls positively or negatively. For example, it might be expected that the Freeman’s Journal, a Catholic newspaper aimed at the Irish diaspora in Australia, would form a nicer opinion of the Irish girls than a conservative newspaper such as the Sydney Morning Herald who generally appealed to a more conservative British or authority-oriented audience.[3]

Forced migration of Irish orphans

Henry George Grey, 3rd Earl Grey. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Immigration to Australia for Irish workhouse orphans was not a new phenomenon. In the years prior to the famine many young people arrived in or were sent to workhouses. This was the last resort for paupers, the poorest of the poor, and one the government recognised as a short term solution to a long term problem. Having spent inside, the opportunities for orphans – some of whom were not actually orphaned but sometimes ‘abandoned’ or ‘left inside’ by desperate parents – were limited if they ever got out. It was the government’s belief that Grey’s proposals to send these children to Australia would ease the problems associated with Irish workhouses – like overcrowding and disease – and offer social and economic opportunities to the poor children.[4] Evidence gleaned from the contemporary printed press in Australia demonstrates that the while the scheme was originally successful, it was short lived, as many of the orphans who were sent to Australia experienced many difficulties in their new land. In addition to this, although several thousand children were sent to Australia there is also evidence to suggest that the problems in the Irish workhouses did not change a considerable amount.

One of the rationales for shipping poor, orphaned girls to the Australian colonies was to address a problem of gender imbalance. In the decade prior to the beginning of the Earl Grey scheme, New South Wales had a particularly problematic imbalance with the majority of the 77,000 strong population being male. The previous schemes attempting to bring girls from Ireland to Australia had proved fruitless with a lack of organisation by the colonists resulting in many of these women becoming homeless with many turning to prostitution.[5] Even though schemes like this had already proven to be quite unsuccessful, there were conflicting ideas shown in the press at the potential of several more thousand females arriving to Australia.

The South Australian newspaper based in Adelaide stated in September 1848 that an ‘erroneous impression’ had been made of Irish orphan immigration to Australia. It was expected that as the girls came from the workhouses they would have a decent standard of training for work and settle well as loyal servants. It was also noted that the architects of the scheme had stated that ‘fair wages shall be paid by the employers, according to the current rate prevailing in the district’ with a deduction for clothing and expenses. However, the unnamed author of the report objected to the rate of wages – £5 per annum for girls aged 14 going up to £11 per annum by age 18 and £8 per annum for boys of 14, going up to £14 for 18 year olds. This would put these children on higher wages than servants in England. Moreover, the word from New South Wales was that servants who had previously been on a low diet were expensive:

‘they eat voraciously … ten shillings per week will barely keep them in victuals’.[6]

‘Downing Street experimentation’

A month later, in October 1848, the Geelong Advertiser in Victoria reported scepticism at the prospect of thousands of Irish orphans arriving to Australia. Written in the aftermath of the first ship to arrive in Australia with two hundred Irish immigrants, a lengthy commentary in the newspaper seemed to push the idea that the scheme was more of an experiment, and if all went well, it would allow for mass immigration from Ireland. Some of the resistance stemmed from the fact that the Earl Grey scheme was being funded by the colonies themselves rather than the Ireland or the United Kingdom. The value of the orphans coming from Ireland was also questioned not least because of their ages and experience; all orphans who took the voyage to Australia were required to be between the ages of fourteen and eighteen, and their value as labourers was disputed. It was felt that as the immigrants were not of adult age, that it would have been fairer if the imperial government shared the cost as these children could not perform hard labour.[7] As Trevor McClaughlin has written, this is a particularly important point as it made the Irish orphan girls far less desirable to potential employers. [8]

As the immigration process was completely funded by the colonies, many colonists evidently felt that this money would be better spent elsewhere. With this being the case, some had already inherited a sense of bitterness against the Irish orphans which would intensify in the future. Many areas of New South Wales already held an anti-Irish sentiment, so the fact that they would have to pay for thousands more to immigrate did not help the cause of the Irish orphans. This particular opinion was also expressed by in South Australia, where a column printed in the South Australian Register and republished in The Port Phillip Patriot and Morning Advertiser in Victoria, referred to the scheme as ‘political quackery’ and ‘Downing Street experimentation’. The unnamed author complained that those in charge of the scheme ‘cannot send us emigrants of the right sort’, emphasising the fact that the colonies would be the ones to pay for these people. [9] It was evident that there was significant – and mounting – press pressure for the Earl Grey scheme to be successful; however little would change from the schemes of previous eras.

As the process of bringing the orphan girls from the workhouses to Australia continued from 1848 into 1849, levels of bitterness and discontent at the decision began to surface. In a letter written to The Charleville Times in Brisbane, Quuensland, ‘an East Anglian’ expressed his frustration at the fact that similar opportunities were not being granted to the poor girls of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk in England, and sensed some favouritism towards Ireland:

‘Are the peasantry of the counties I have named less loyal or less industrious than the Irish?’[10]

However, even with many people holding a negative impression of the girls, the evidence suggests that the girls who travelled to Australia in 1849 assimilated well and were employed quickly. There was clearly a conscientious effort being made by the guardians of the workhouses and officers of Poor Law unions in Ireland to select only girls who were of sound health and mind to travel. This policy was implemented in order to ensure that only the ‘best’ made their way to the Australian colonies that would pay for them.

According to Joseph Robins’ research, despite the early success of the scheme in which the girls settled in quickly and were of good health as promised, there was still serious opposition to the scheme. During 1849 the opposition was more concerned with the exclusion of the English and Scottish and the opportunities that might be offered to the poor of those parts of the United Kingdom. However, efforts were made in order to try including English and Scottish children in the scheme; indeed, the Catholic Bishop of Adelaide passed a resolution calling for this to be happen in South Australia.[11]

Anti-Irishness?

Some newspapers tried their best in order to defend the Irish girls that arrived from expressions harassment and abuse. In early 1849, The South Australian published an editorial seeking sympathy for the girls who made the voyage: ‘Whether the introduction of these young people is to be a blessing or a curse to them and to the colony will much depend upon ourselves.’[12] Adopting a rather heartfelt tone, the newspaper reminded the public of the difficulties that these children experienced in their young lives and that their value to the colony would depend on how they are treated by the public. It entreated the colonists of South Australia to think of themselves in loco parentis for parentless children and consider if it was really possible to bind them to their employers. It asked them to consider if the apprenticeships which many were expected to serve were really workable with the high wages available for in demand female domestics or if the jail punishments that faced those who broke their apprenticeship conditions were appropriate. It called for an end to the apprenticing system, ‘so far as regards domestic servants’ so that the Irish orphans might ‘serve in freedom – to serve for wages which will satisfy them-to take a new place, if they do not like their old one – ay, and to become matrons, should it please them, as the other young maidens of South Australia can do.’

This certainly was not an opinion shared by all newspapers and people. The longer that the scheme went on, the more problems that began to arise and the more fuel to those who never agreed with the scheme in the first instance. It was apparent that as the scheme began to fail in 1850, many people had enough of Irish girls apparently failing to contribute. This was evident in more conservative news outlets such as The Argus based in Melbourne, Victoria. In a very lengthy and particularly damning editorial in this paper, the focus was again on the cost of bringing the girls to Australia, with a particular resentment against the British government for not bearing at least some of the cost. Even so, it was claimed that even if the British government covered the cost, it would not make up for bringing over such ‘miserable paupers’,

‘coarse, useless creatures, whose very personel, with their squat, stunted figures, thick waists, and clumsy ankles, promises but badly for the physique of the future colonists of Victoria.’

The money of the people would be better spent bringing over ‘the rosy cheeked girls of England’, ‘lasses of bonnie Scotland’ or even a ‘better description of the bright-eyed daughters of Erin’. It is clear that this newspaper held an anti-Irish, or more specifically an anti-Catholic agenda, warning male colonists that the Irish orphan girls were ‘exclusively Roman Catholic; their main and avowed object, in coming here, is to get married’. The result of matches with Australian men, however poor, would be that:

‘if the children have any religion at all, they will be Roman Catholics to an individual; the mother will dictate the religion of the family, and every one of these girls will some day be the centre of a Roman Catholic circle.’[13]

Although efforts were made by different parties in order to try and improve the life of Irish immigrants during this time, little changed and many Irish in South Australia succumbed to a life of poverty. At the time the average Irish income was relatively lower than that compared to their English or Scottish counterparts. During this two year period the quality of life for Irish people did not change a considerable amount in South Australia or indeed in the workhouses of Ireland. In 1850 the opposition against the Earl Grey scheme was so strong that it was eventually ceased with the last ship Tippoo Saib arriving to Australia in July of that year. In September, The Cornwall Chronicle in Tasmania, reported on intelligence from Sydney on the matter, including a legislative council meeting that justified the end of the scheme on several grounds not least the cost which was estimated at in excess of 40,000 pounds as well as additional maintenance fees once the girls arrived. Furthermore it was implied that the people of Sydney felt cheated, as if the girls were sent for the gain of Ireland rather than Australia; this was not to discredit the girls but criticise those who sent them over instead.[14]

Irish famine memorial in Sydney, dedicated to the 4,114 Irish Famine girls. Source: Emerald Heritage

Most newspapers across the Australian colonies seemed to agree that although the Earl Grey scheme was successful in its initial stages, by 1850 there were too many girls arriving in Australia at the one time and not enough of them reaching the areas with severely disproportionate ratios of men to women. It was apparent too that some areas had treated the girls much worse than others. As Robins had demonstrated, Adelaide in particular had shown particular hostility towards the girls. Many of those who were unable to assimilate into Adelaide went into a life of crime or prostitution more so than other areas. This was an extremely disappointing conclusion for those who had hoped to escape poverty and make a new life for themselves.[15] The press portrayal of the girls over the course of the two years of the scheme fluctuated in some cases and in other cases it did not change at all. Depending on the newspaper, either great optimism or pessimism was shown at the prospect and development of the scheme. There is no doubt that the conservative press mirrored some public opinions but may also have contributed to the harassment that girls received even against the best efforts of other news sources who tried to defend them. The Irish orphan girls that arrived in Australia during the Great Famine left until what was until relatively recently a forgotten legacy; their story has been revived mainly due to the efforts of groups such as the Historic Houses Trust of NSW who commissioned the building of a memorial to the girls in Sydney.[16]

REFERENCES

[1] Dawn Joy Ralfe, Murders and mayhem at Salt Creek (Coorong, 2014), pp 37-8.

[2] Joseph Robins, The lost children (Dublin, 1987), pp 200-1.

[3] Eric Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’ in Irish Historical Studies, 107 (1991), pp 223-25.

[4] Joseph Robins, ‘Irish Orphan Emigration to Australia 1848-1850’ in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 228 (1968), pp 372-3.

[5] Alan Hayes and Diane Urquhart, The Irish women’s history reader (London, 2001), pp 168-9.

[6] The South Australian, 12 Sep. 1848, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/71612382/6251679) (20 April 2018)

[7] Geelong Advertiser, 12 Oct. 1848, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/8142583?) (20 April 2018)

[8] Trevor McClaughlin, ‘Lost children? Irish famine orphans in Australia’ in History Ireland, no. 4 (2000), pp 30-2.

[9] The Port Phillip Patriot and Morning Advertiser, 23 Sep. 1848, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/226353970) (20 April 2018)

[10] The Charleville Times, 8 Dec. 1849, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/79593960?searchTerm=irish&searchLimits=l-title=274|||l-decade=194|||l-year=1949|||l-month=12) (20 April 2018)

[11] Robins, ‘Irish orphan immigration’, pp 373-5.

[12] South Australian, 26 Jan, 1849, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/71622984) (20 April 2018)

[13] The Argus, 24 Jan. 1850, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4771328) (20 April 2018)

[14] Cornwall Chronicle, 7 Sep, 1850, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/65975651) (20 April 2018)

[15] Robins, The lost children, 220-1.

[16] See the Historic Houses Trust of NSW, incorporating Sydney Living Museums, website: www.sydneylivingmuseums.com.au