The front of the school prospectus, 1817. From the Brisbane Girls’ Grammar school website.

The historiographical analysis of the Irish women in Australia is reflective of how they were contemporaneously treated. The history of these women has been widely neglected – especially in the context of education. The following study will explore the Irish female impact on Australian education and will break away from the idea – popular among previous historians – that all Irish females were convict women, and so were generally invaluable for Australian society. This analysis will focus on a girls’ institution in Queensland and how the Irish female teachers of the school were perceived. The Brisbane Girls Grammar School was established in March of 1875. This was the first girl’s grammar school in the Australian colonies and was set up under the Queensland Grammar Schools Act of 1860.[1] Although established one hundred years after the first fleet arrived in New South Wales, it’s development is key in the study of the Irish female experience as students and educators in Australia.

The First Lady Principal

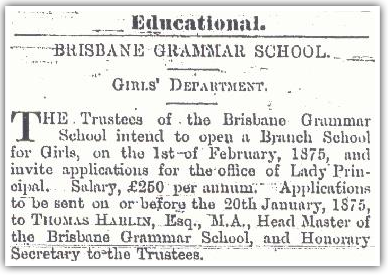

Newspaper advertisement for a Lady Principal, 1875. The Argus, 2 Jan 1875. Source: Trove.

An advertisement in The Argus, a Victorian newspaper, details the boys’ grammar school of Brisbane’s intent to establish a girls’ school. They were advertising for a woman to fill the role as principal. ‘The trustees of the Brisbane Grammar School intend to open a branch school for girls on the 1st of February, 1875, and invited applications for the office of lady principal. Salary, £250 per annum.’[2] This particular advertisement was written by Thomas Harlin, the headmaster of the Brisbane (boys’) Grammar School. There were over five hundred advertisements for girls’ schools in The Argus after the passing of the Queensland Grammar School Act of 1860. Janet O’ Connor was assigned the school’s principal in March of 1875. The name ‘O’ Connor’ is most commonly known as a name of Irish descent, specifically the name of the 10th-century king of Connacht.[3] In Irish legend, ‘Conchobhar’ was the King of Ulster and the name O’ Connor is said to be an anglicised version of his name.[4] As there are no ancestral records for Janet O’ Connor, one must mention that she is likely to be married to an Irish man or of Irish descent herself.

Photograph of Janet O’ Connor, first female principal, 1875. From the Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School website.

A newspaper article that surfaced in The Brisbane Courier eight months after her start as ‘Lady Principal’ outlines details about her resignation. This article was written by the original male Trustees of the boys’ Grammar school. It informs us that it ‘had been arranged that the masters of the grammar school should attend the girls school to give assistance’ to Mrs O’ Connor.[5] It also details how she felt it unnecessary. The male writers go on to say that ‘if the trustees were furnished with the timetable of the school, they might be able to help the Lady Principal.’[6] They add that ‘she was a lady of high culture and attainment; but she had lacked judgement.’ ‘She seemed to be not able to work with a governing body’ and this ‘might render her an invaluable teacher.’[7] This article goes into detail about the problems that the school had faced – including an illness epidemic. The article is not in favour of Mrs O’ Connor. Not only do they imply that she needs help with running the school but they also place the blame on her for any problems that have arose. All the time, the writers refer to the fact that they – males – should help her run the establishment. The context of the Brisbane Courier is important. Sir Charles Lilley – the creator of the Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School and chairman of both the girls’ and boy’s Board of Trustees – worked as the editor for the Brisbane Courier for several years.[8] This context added a certain questionable undertone to the article as we cannot ignore the fact that Sir Charles Lilley may have had an influence on his previous employers.

Irish women were ‘ignorant, none were capable of teaching and few were inclined to learn.’

The two previous articles were written by men. Miriam Dixson of The Real Matilda has proclaimed that the Australian ‘education system produces women who are incompetent and self-denigrating’.[9] She goes on to explain that Australian society is sexist and makes girls feel and believe that women are of a lower status than men.[10] When studying Australian history, especially in the former years of the colonies, it is evident that the history is written by men about men.[11] This is the way Irish female teachers are being documented – or are not. Noeline Kyle opens her article with a conversation between a man and a woman with whom he wants to employ as a teacher, it reads;

‘“Can you do as you’re told?” Yes, sir. “Can you play cricket?” Yes, sir. “Then I will have you.” And she went.’[12]

This source depicts the popular idea of the patriarchal society that Australian is often written as in history books. One could note that the depiction of the weak female teacher in Australian historiography is due to a lack of evidence. It must be mentioned that the primary materials based on female educators and their worth are available. However, the secondary material has not been updated and so in insufficient in portraying these Irish women and their influence.

‘Damned bitches and prostitutes’?

Brisbane was a prosperous place for young female’s during the second half of the nineteenth century and this girls’ grammar school is an explicit example of this. Isabella Whyly, an Irish emigrant living in Brisbane, speaks lovingly of another young Irish girl also living in Brisbane; Mary Carrigg. Isabella writes home to her sister Matilda Whyly in Ireland: ‘she is a big girl growing very tall her mother tells me. She is assistant teacher along with a respectable Lady in Brisbane.’[13] This first account already speaks of the Irish female contribution to the Australian education system and juxtaposes the views of many historians who have taken the argument that Irish women were incapable and ‘very ignorant, none were capable of teaching and few were inclined to learn.’[14] However, there are numerous primary accounts of letters detailing this young Irish girl’s success in Australia. We are told that Mary Carrigg ‘is a fine girl and going to School every day’ and that even as ‘an illiterate eleven-year-old’, ‘she has become an assistant teacher’.[15] Michael Normile goes on to mention that her family are ‘doing remarkably well and that Mary Carrigg is a clever looking girl and well educated.’[16] The examples of female teachers only grew in abundance as the nineteenth century unfolded.

Amy Barrington’s book, A Family History, 1917. From Exlibris Rosetta.

Amy Barrington was an Irish lady who became a teacher at the Brisbane school for girls in 1888. It is clear from reading Amy Barrington’s own account of her family history that she was a passionate and dedicated teacher at the Australian school. She states that ‘for twenty-six years I was too much occupied in learning, teaching and travelling, to give further thought to anything else.’[17] She continued to teach in various schools around Australia and became a successful scientist, undergoing studies into improving human genetic quality.

The widespread perception of Irish convicts, and more so Irish female convicts is not a positive one. They have been portrayed as ‘damned bitches and prostitutes’ by writers such as Robert Hughes in his 1986 book, The Fatal Shore.[18] These women have been written about based on male writers, such as Hughes, making connections between modern assumptions’.[19] However, when primary source material is delved into further this assumption can be replaced. Another local newspaper of Brisbane, The Telegraph had the Girls’ Grammar School at the focus of an article titled ‘The Girls’ Grammar School’. What is presented is a piece writing by the female students as a token of their appreciation for Mrs. O Connor. The article summarises for the reader the respectful relationship shared between the teachers and students. The letter within this article reads, ‘Dear Madam, – We, the pupils of the Brisbane School, request you to accept this gift as a token of the high esteem in which you are held by us.’[20] The principal reacts pleasantly and explains that it was ‘one of the most pleasant surprises she had ever experienced’.[21] Also in the article, it details how the ‘scholars then amused themselves with dancing and music’[22] after the ceremony had concluded. This tells us of the vast range of subject choice and physical education being pursued by the students, under their female principal. Another quote that should be noted is the explanation that ‘when the male teachers withdrew their services’ at the school, the women had ‘shown themselves equal to the emergency’.[23] This example does not describe the humility of nineteenth century women teachers and how these women’s lives were circumscribed by economic precariousness and sexist expectations, but instead deals with the success story that is Janet O’ Connor and the Brisbane Girls Grammar School. [24]

Brisbane Girls Grammar students standing outside their new school at Wickham Terrace, 1875. From the Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School website.

No religious impact?

Another important aspect of this study is the exclusion of religion from the teachings and overall running of the institution in Brisbane. Marjorie Theobald tells us that the headmistress of the Brisbane Grammar School did not attempt to introduce prayer to the daily lessons until the mid-1980’s.[25] This meant less discrimination for the students and teachers. Stephanie Burley tells us that religion had a major impact on the treatment of women in the education sector and especially on Irish Catholic women. She goes on to speak about the fact that female religious teachers worked for the British Empire, while also trying to maintain aspects of their Irish backgrounds and also, their womanhood – whist ‘formulating their spiritual and professional identities in a new land’.[27] Irish female teachers are a minority within a minority in many cases and are often only written about in this way. Kay Daniels reminds us that education records and payslips reveal the ways that women were ‘led into that low self-esteem which Australian historians seem to wrote about as a natural ‘womanly’ response to a society whose early members were convicts’.[28] The fact that the school in Brisbane did not introduce religion until over one hundred years after its opening, meant that it’s discriminative nature was also excluded.

Photograph of the Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School, 1885. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The historiography around education portrays an Australia where the teachers were predominately male or ‘expendable’ females.[29] However, through an analysis of primary sources the Irish female contribution to the Australian education sector becomes evident. Thus, proving that these women indeed not ‘expendable’ figures in society but, in fact, played a vital role in Australia’s education system. The Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School serves an important point of reference regarding female education and female teachers. The mentioned Irish females conducted their role as educators in responsible and successful manners. Amy Barrington, Janet O’ Connor and Mary Carrigg can be used as examples of women who did not simply nod ‘Yes, sir’ to their patriarchal society.[30] The newspapers and letters provide accounts of the Irish ladies’ success regarding the education sector in an Australia. A place that had come to be known as masculine and harsh – by historians and its civilians. The exclusion of religion in the grammar school of Queensland made it so there was no segregation between pupils. Overall, the research has shown the ways in which Irish female teachers were perceived and how they combated this perception in the long nineteenth century.

Further Reading:

[1] Marjorie R. Theobald, Knowing Women: Origins of Women’s Education in Nineteenth-Century Australia (Cambridge, 1996), p. 95.

[2] ‘Brisbane Grammar School – The Argus – 2 Jan 1875’ in Trove, 2017 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/11510009?searchTerm=brisbane%20girls%20grammar%20school&searchLimits=sortby=date) (21 Mar. 2017).

[3] ‘O’ Connor Name Meaning & O’ Connor Family History at Ancestry.com’ in Ancestry.com, 2017 (http://www.ancestry.com/name-origin?surname=o%27connor) (21 Mar. 2017).

[4] ‘The Girls’ Grammar School – The Brisbane Courier – 16 Nov 1875’ in Trove, 2017 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1384391?searchTerm=brisbane%20girls%20grammar%20school%201875&searchLimits=) (21 Mar. 2017)

[5] ‘Historical Timeline – Lilley’s Vision, Education for Girls’ in Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School, 2017 (https://www.bggs.qld.edu.au/about/history/) (19 Mar. 2017).

[6] Miriam Dixson, The real Matilda: women and identity in Australia, 1788 to the present (New South Wales, 1999), p. 39.

[7] Noeline Kyle, ‘Can You Do as You’re Told? The nineteenth-century preparation of a female teacher in England and Australia’ in Comparative Education Review, 4 (1992), p. 467.

[8] David Fitzpatrick, Oceans of Consolation: Personal accounts of Irish migration to Australia (Ithaca, 1994), p. 105.

[9] Jon Kavanagh and Diana Snowden, Van Diemen’s Women: A History of Transportation to Tasmania (London, 2015), p. 143.

[10] Fitzpatrick, Oceans of Consolation, p. 54.

[11] Amy Barrington, Barrington’s, a family history (Essex, 1917), p. 1.

[12] Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore (London, 1986), pp 212-247.

[13] ‘The Girls’ Grammar School – The Telegraph – 24 Dec 1875’ in Trove, 2017 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/169490817?searchTerm=brisbane%20girls%20grammar%20school%201875&searchLimits=) (21 Mar. 2017).

[14] Kay Daniels, ‘Women in Australia: An annotated guide to records’ in History Workshop, 7 (1979), p. 190.

[15] Theobald, Knowing Women, p. 95.

[16] Stephanie Burley, ‘Engagement with empires: Irish Catholic female religious teachers in colonial South Australia 1868-1901’ in Irish Educational Studies, 2 (2011), p. 176.

[17] Burley, ‘Engagement with empires’, p. 176.

[18] Daniels, ‘Women in Australia’, p. 190.

[19] Sally Kennedy, ‘Useful and expendable: Women teachers in Western Australia in the 1920s and 1930s’ in Labour History, 44 (1983), p. 18.

[20] Kyle, ‘Can You Do as You’re Told?’, p. 467.