Bushrangers, 1852, by William Strutt. On display at the National Library, Canberra.

The general public’s fascination with Australian bushrangers has contributed significantly to the stereotyping in common dialogues of all Irish immigrants as only convicts, as it is the tales of crime and life on the run that intrigue many. Therefore, such negative stereotypes emerge as dominating narratives of the Irish immigrant experience in Australia in relation to law and order. The need to dismantle these stereotypes is crucial in order to examine the complexities and variations in the overall Irish immigrant experience. Irish immigrants in Australia had a variety of roles and reasons for emigrating to Australia, and to label all immigrants as criminals nullifies the complexities of the individual experience. However, investigation into the bushrangers of Australia is necessary in order to understand this dominating narrative and opinion of Irish immigrants as well as understanding the complexities of the Irish input into law and order in Australia. In order to explore and understand these stereotypes, Martin Cash will be taken as an example of such a bushranger and his portrayal, glorification and self-representation, through his autobiography, will be examined. Examples will be drawn on other famous bushrangers for the sake of providing a broader narrative on the balance of law and order in relation to the Irish immigrant experience. While many Irish immigrants contributed to the maintenance of law and order, there were few, like Martin Cash, who did not conform to the legal system established in Australia.

Biography

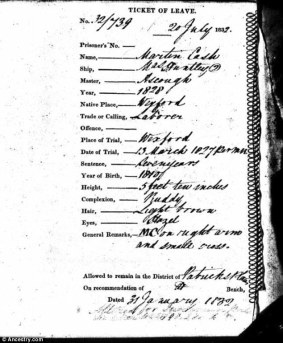

The New South Wales ticket-of-leave given to Martin Cash on the 20th July, 1832. From: Ancestry.

Martin Cash was a native to Enniscorthy in county Wexford, Ireland, who was convicted and transported to Sydney in 1827.[1] Having later been transported for his sentence to Port Arthur in Van Diemen’s Land, now known as Tasmania, Cash became famous for his successful escape attempts and surviving shark infested water, which would precede his career as a bushranger.[2] Upon attempting to escape arrest, he killed a constable and evaded the death penalty, being sent to Norfolk Island, between Australia and New Zealand, instead for ten years.[3] Following a ticket-of-leave, an allowance offered to prisoners who had served part of their sentence, Cash was appointed as a constable in the Canterbury Province Police Armed force briefly but later proceeded to manage brothels in Christchurch, New Zealand.[4] However, he was put out of business by officials out of the fear he would lure other criminals or bushrangers to the area.[5] Cash was the only notorious bushranger to die of old age, after living his later years farming in Van Diemen’s Land.[6] During his bushranging career, Martin Cash was notorious for his gentlemanly manners, limited use of unnecessary violence and predominantly targeting rich individuals which coined him the name: ‘The Robin Hood of Van Diemen’s Land’.[7]

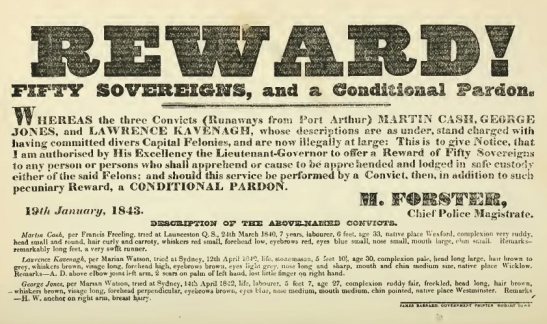

Martin Cash’s career of crime lacks significant details in the historiography surrounding him. Limited narratives of his bushranging have been provided in various secondary sources, summarising his career as robbing of inns and wealthy settlers’ houses, all on foot as opposed to the traditional means of horseback.[8] However, articles in contemporary newspapers exist warranting his arrest and calling for assistance that may contribute to his capture. Rewards were offered, such as a choice between 100 acres of land or 100 sovereigns, or simply the monetary reward if one was a convict.[9] By the time Cash killed a man, Peter Winstanley, and wounded others who were trying to capture him, interest in his career and life was widespread throughout Australia and his final run ins with the law were given significant attention. He was deemed an ‘unhappy man’ and upon taking to the bush as a means of escape was condemned to death, either at the hands of the law or of the dangerous nature of the Australian outback.[10] Having later been arrested and put on trial, Cash displayed his gentlemanly manners and behaviour, pleading his case at his trial: ‘if I should have to fire I would try not to kill a man’ and proceeded to claim ‘If I had been a man to do violence, there would have been a deal of murders committed since I have been in the bush’.[11] At which point, it was deemed Cash had successfully pleaded his case and was remanded, evading the death penalty and was instead sentenced to ten years in Norfolk Island, which was in its final phases of penal settlement. Here, Cash would become a model prisoner and slowly earn responsibility and authority, and eventually his freedom. His experiences of abiding by the law have been unaccounted for in the newspapers of the time, by contrast with the exposure he received during a life of crime. It is this lack in the narrative of everyday experiences of Irish immigrants that aids the stereotyping of Irish immigrants as criminals as the normal and legal exploits of such people are uninteresting or deemed unworthy of note in both newspapers and general paperwork of the time.

Reward poster for Martin Cash, 1843. From: Charles White, History of Australian Bushranging (Australia, 2012).

Upon Martin Cash’s death in 1877, many newspapers regaled his tales of crime and boasted of his ‘life of such excitement’.[12] He was accredited to being the ‘head of a band of bushrangers’ and praised for being the ‘terror of the whole colony’.[13] His death was dealt with softly and kindly, referring to his shooting of his wife’s mistress as a ‘love rival’, almost condoning his behaviour as an act of passion.[14] Even the postscript added to his autobiography paints the idyllic passing of his life which was deemed ‘peaceful’ and comfortable having enjoyed ‘the good will of all’.[15] Although, Cash lived out his final years free of crime and out of the eyes of the law, similar bushrangers, who did not repent, such as Ben Hall and Ned Kelly were dealt with softly when reporting the news of their death. Hall was referred to as ‘worthy’ and as a ‘victim’[16] while reports of Ned Kelly’s sentencing sympathised with him that he ‘suffered the extreme penalty’.[17]

Martin Cash’s final residence, Montrose, Tasmania. From: The companion to Tasmanian history.

Martin Cash’s grave, labelling him a ‘brave but unfortunate Irishman’. From: Find a grave.

The historiography and his legacy

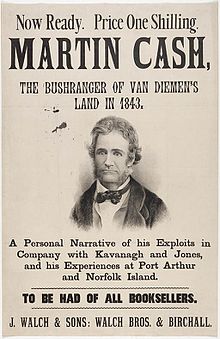

Cash’s tell all autobiography was published in Tasmania seven years prior to his death,

which was entitled Martin Cash: the bushranger of Van Diemen’s Land in 1843. A personal narrative of his exploits in the bush and his experiences at Port Arthur and Norfolk Island.

Poster for Martin Cash’s autobiography, 1870. From: Dictionary of Sydney.

Through this autobiography a structured outline of his life and exploits remain amongst the historical narrative surrounding him. However, criticism remains that Cash’s accounts, edited by James Lester Burke, have been embellished and provide ‘a rather coloured version of the truth’.[18] Despite this, Martin Cash’s career as a bushranger, or as the ‘Robin Hood of Van Diemen’s Land’, remains an interesting phenomenon, his autobiography having been reedited and printed as recently as 1991 as The uncensored story of Martin Cash: the Australian bushranger as told to James Lester Burke.[19] The original version of his accounts was very popular and was therefore reprinted on a multitude of occasions, thus proving the interest in and fascination with the lives of those outside the law.[20] The fact that his accounts have been reedited for modern consumption is simply proof of the interest in the lives of bushrangers over the average immigrant, which therefore contributes to the stereotyping of Irish immigrants as solely criminals as it is the information that is commonly mass consumed. Despite the embellishment of his own tales, Martin Cash clearly understood the fascination with bushrangers and through understanding this, simply entertained the masses by providing the story they wanted of hardship, excitement, near misses and adventure.

The legacy of Martin Cash and his gang, Cash and Company, has remained in many modern mediums and forms. A song entitled ‘Cash & Company’ recorded by Lionel Long, in a collection entitled The Wild Colonial Boys, was released in 1963. ‘Cash & Company’ provides a light hearted and whimsical account of Martin Cash’s exploits, with terms such as ‘cattle dealing’ to mean cattle stealing, ‘gentlemanly argument’ to stand for fighting and sending ‘a friend to heaven’ meaning killing.[21] It is this downplay of crime that promotes the idea that the bushrangers pursued noble endeavours and remained relatively innocent, depicting them as heroes of the lower classes and garnering affection for their audacity worldwide. There are few famous or entertaining poems or ballads written about the average Irish labouring immigrant who led a life of simple farming in Australia and therefore such narratives and experiences are lost amongst the shining fame of the bushrangers, or Irish criminals. The attachment and promotion of this daring bushranger image over that of a criminal is found widely in Australian culture. Even the unofficial anthem of Australia, ‘Waltzing Matilda’, written by Banjo Paterson in 1895, romanticises the image of the bushranger, camping and singing by a pool evading his capture through death, remaining as a ghost forever free to roam the outback as an outlaw. Only a couple of decades after his death, the story of Martin Cash was frequently adapted for the stage. In 1899, a play was to be staged under the instruction of W.P. O’Callaghan in the town of Zeehan, Tasmania. The play claimed that Cash’s name was famous amongst ‘every Australian’ and promised ‘exciting situations’ as expected of the famous man, even 22 years after his death.[22] In 1900, Cash’s own autobiography was adapted into a play entitled ‘Martin Cash, the bushranger’ performed by a group of drama students in the city of Launceston, Tasmania, which aimed to be a comedy depicting Cash as a ‘decidedly humorous character’.[23] The presentation of the stereotypical Irish bushranger in Australia proved to be a profitable and entertaining business, both to those who Cash was a familiar to and those few unaware of his life but enjoyable nonetheless.

Concluding comments

Martin Cash has clearly been depicted as a hero, having led a life predominantly guided by crime, he did so with a reputation as a ‘gentleman’.[24] To live an exciting life of crime and still be commended for it is an unusual occurrence but an endearing story nonetheless. Perhaps it is the fondness present in dealing with characters such as Martin Cash, whether it be through awe of his daring misdemeanours or the respectability he presented himself with, that he has become a figure of legend both in Tasmania today and in Australia. The respect and affection in his portrayal is admirable, captivating and charming. One can accredit this treatment of a bushranger, or criminal, to the attachment of stereotypes of Irish immigrants as solely criminals. Both Irish families, with relatives who emigrated, and Australian families of Irish descent can attribute their origins or connections to the commendable and legendary cowboys of Australia, the criminal bushrangers. As such origins are traditionally stereotyped as criminal anyway, the elevation of the bushranger connotes a sense of pride in origin, even if it is just a sliver of the Irish immigrant experience in Australia, despite stereotypes.

Film poster for The legend of Ben Hall, released December 2016. Ben Hall being a similary famous bushranger who has been glorified posthumously. From: Goulburn post.

Bibliography

[1] L.L. Robson and Russel Ward, ‘Cash, Martin (1808-1877)’ 1966, Australian dictionary of biography, National centre of biography, Australian National University, (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cash-martin-1885) (3 April 2017).

[2] Ibid.

[3] David Green, ‘Cash, Martin (1808-1877)’ 1990, The dictionary of New Zealand biography, Te Ara: the encyclopaedia of New Zealand (http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1c9/cash-martin) (3 April 2017).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Robson and Ward, ‘Cash, Martin (1808-1877)’.

[9] ‘Reward of one hundred acres of land, or one hundred sovereigns!’, The Courier, 14 July 1843, p. 4 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2952458?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits=l-decade=184) (3 April 2017).

[10] ‘Van Diemen’s Land’, Melbourne times, 15 September 1843, p. 2 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/226925517?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits=l-decade=184 ) (3 April 2017).

[11] ‘Trial of Martin Cash’, Launceston examiner, 16 September 1843, p. 5 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36234635?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits=l-decade=184) (3 April 2017).

[12] ‘Death of Martin Cash’, Tribune, 29 August 1877, p. 2 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/201732686?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits) (3 April 2017).

[13] ‘The late Martin Cash’, Weekly Examiner, 1 September 1877, p. 13 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/233677001?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits=l-decade=187) (3 April 2017).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Martin Cash, Martin Cash: the bushranger of Van Diemen’s Land in 1843. A personal narrative of his exploits in the bush and his experiences at Port Arthur (Tasmania, 1870), Hathi trust digital library (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnp1dn;view=1up;seq=187) (3 April 2017).

[16] ‘Death of Ben Hall’, Freeman’s Journal, 6 May 1876, p. 18 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/115300380?searchTerm=ben%20hall&searchLimits=l-decade=187) (3 April 2017).

[17] Execution of Ned Kelly’, Launceston examiner, 12 November 1880, p. 3 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/38264399?searchTerm=ned%20kelly%20death&-earchLimits=l-decade=188|||l-year=1880|||l-month=11) (3 April 2017).

[18] Robson and Ward, ‘Cash, Martin (1808-1877)’.

[19] Joan Dehile Emberg and Buck Thor Emberg, The uncensored story of Martin Cash: the Australian bushranger as told to James Lester Burke (New Delhi, 1991).

[20] Robson and Ward, ‘Cash, Martin (1808-1877)’.

[21] Lionel Long, Cash & Co, 2011 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eV8Z0ewrvfg) (30 March 2017).

[22] ‘Martin Cash’, Zeehan and Dundas herald, 4 July 1899, p.2 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/84671580?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits) (2 April 2017).

[23] ‘Martin Cash, the bushranger’, Examiner, 15 Dec. 1900, p.6 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/35382040?searchTerm=cash%20martin&searchLimits) (2 April 2017).

[24] Robson and Ward, ‘Cash, Martin (1808-1877)’.

Further reading/research

Manning Clark, A history of Australia: volume iv: The earth abideth for ever 1851-1888 (London, 1992), pp 165-219 (‘The bush barbarians’), pp 319-356 (‘Uproar in the bush’).

Paul Eggert, ‘The bushranger’s voice: Peter Carey’s “True history of the Kelly Gang” (2000) and Ned Kelly’s “Jerilderie Letter” (1879)’ in College Literature, 34 (2007), pp 120-139.

Kelly Fuller, Lauren Fitzgerald and Jennifer Ingall, Who isn’t related to a bush ranger? (New England, 2010), ABC New England North West (http://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2010/08/10/2979127.htm) (26 April 2017).

Pat O’Malley, ‘Class conflict, land and social banditry: bushranging in the nineteenth century Australia’ in Social problems, 26 (1979), pp 271-283.