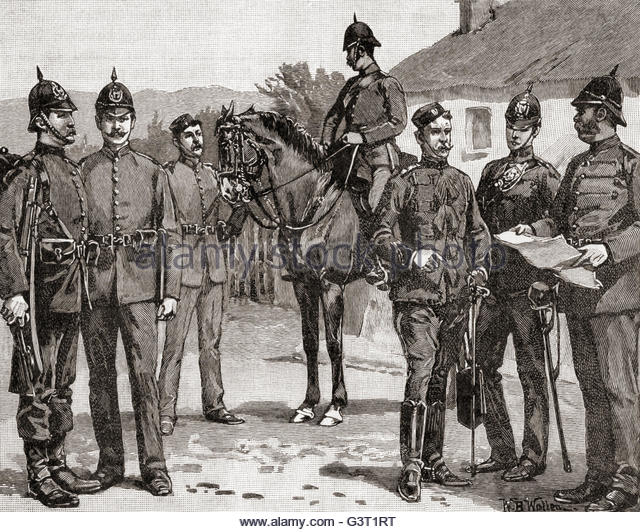

Officers and men of the Royal Irish Constabulary in the nineteenth century

The role of the Irish in colonial Australia’s law enforcement during the nineteenth century is an area that requires some broader examination from a historical perspective. Eric Richard’s states that ‘They were over-represented in the police force and amongst the magistracy.’[1] However, while there are a wealth of sources that deal with the Irish immigrant experience in Australia and some that deal with Australia’s colonial police force, there are few sources in which these two areas intersect. In such terms, this post will try to clarify the nature of Irish immigrants’ contribution to law enforcement in Australia during the colonial period by examining some primary texts based on the lives of Irish Australian police officers, including their origins, personalities, cultural affiliations and careers. Secondary sources provide context to both the immigrant experience and also the nature of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the police force from which many of these Irish police officers were drawn or from which they had left in order to travel to Australia.

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC): a colonial policing template

The RIC was a police force established by the British in order to police the island of Ireland during the considerably tumultuous period for the island that was the nineteenth century. Originally organised in 1814, and reorganised in 1836, this force policed Ireland during the Great Famine (c.1845-52), the rise of nationalism and eventually the Irish War of Independence (1919-21). One of the first demonstrations of its efficiency was its putting down of the Young Ireland rebellion in 1848, a separatist uprising led by William Smith O’Brien (who was deported to Van Diemen’s Land). In some ways, the establishment of the RIC was an acknowledgement of Ireland’s position in the British Empire as a colony, rather than an as a constituent part of the United Kingdom in the same way that England, Scotland and Wales were. As Georgina Sinclair had argued: ‘policing Ireland had been the starting point for the colonial–police tradition.’[2]

RIC men during the Young Ireland rebellion in Ireland, 1848

Indeed, the RIC held many of the traits attributed to colonial police forces including the fact that they were deployed as a police ‘force’ rather than a ‘service’.’[3] The bulk of the force was mainly comprised of policemen native to Ireland and largely of an Anglican background which was in the minority in the country as a whole. Anglicanism was, however, the state religion as established by Britain’s governance. This serves to explain Sinclair’s view of the RIC as a force rather than a service. Employed to police a populace that held the singular but difference of religion led to members being viewed as ‘other’. This led to escalation in tensions that saw insurgency which in turn was met with force. While the merits of the RIC’s police methods have been debated by historians on a moral basis, one aspect remains clear; they had expertise in policing that was contemporaneously unparalleled, particularly in areas where public order was precarious, making them an ideal colonial police force. This expertise led to a strong demand for Irish police officers throughout the British Empire.[4]

James Coulter (1832–1907)

While the RIC was not the singular source of the Irish contingent of the Australian police force, it was certainly a significant one for well-trained officers as evidenced by the careers of police officers such as James Coulter. Coulter was born on 6 September 1832 in Ballysakeery, County Mayo, and went on to have a career that was quite typical of the type outlined above. He followed in his father’s footsteps and joined the RIC in 1852, spending five years stationed in County Cork as a finance clerk until he resigned in 1857, though he was highly commended for his service.[5] In 1858 he arrived in Tasmania and took up the position of sub-inspector. He gained a reputation as a disciplinarian but also as a quiet gentleman. His obituary published in the Daily Telegraph in 1907 described him as:

a seen and capable officer who, whilst standing between the public and the men under him, amply safeguarded the interests of both.[6]

Coulter’s clerical work for the RIC stood to his credit in 1861 when he was made a bench clerk, suspending his career as a police officer. In his time as a legal representative he was commended on his fairness and impartiality and would receive recognition from the Attorney General, Justice Clark, on his retirement years later for dealing fairly in cases concerning the government by which his was employed.[7] In 1866, Coulter became superintendent of the Launceston Municipal Police, in Launceston, Tasmania, and upon his retirement in 1896, he was made a Justice on the Launceston bench.[8] [9] He was credited with contributing significantly to the Launceston Police Provident Fund Act (1878), which allowed officers with fifteen or more years of service to retire at the age of sixty and earn a pension.[10] However, this Act was lost in the centralisation of Australian governmental policies.[11] Outside of his life in law enforcement, Coulter was a leader of his community, investing in and serving on the boards of several local businesses and societies, using his experience as a financier to do so.[12]

Coulter’s career was only representative of one portion of the Irish population in Australia. He had come from an Anglican background and arrived in a country where Anglicanism was the state religion.[13] His religious beliefs and experience with the RIC would have been encouraging factors in terms of his employment by the British Commonwealth administration in Australia. Essentially there were no natural impediments for an officer like Coulter to rise high in Australia’s law enforcement system. It is not unfair to say that, generally, Catholic Irish Immigrants brought less wealth with them to the colonies than their Protestant counterparts.[14] However, Eric Richards notes that: ‘The Irish, both Catholic and Protestant, penetrated at all levels of South Australian society and in all aspects of colony-making’.[15] The career of Martin Brennan offers and interesting counterweight to that of James Coulter’s.

Martin Brennan (1839–1912)

Brennan’s origins bore a stark contrast to Coulter’s and the rough beginnings of his career were entirely dissimilar to Coulter’s clerical role. He was born in 1839 and came from a Catholic farming background in Kilkenny. Described in his obituary as a ‘self-made Australian’, he arrived at New South Wales in 1859 and joined a mounted patrol charged with running a gold escort from Braidwood to Goulburn.[16] He became a senior constable in Moruya in 1862 after the Police Act was issued the same year and gradually rose through the ranks to become a superintendent in 1894. He was heavily involved in the training of fellow officers throughout New South Wales due to his unconventional but highly valuable policing experience.[17] This experience was significant as it included subduing the Lambing Flat Riots, in which he distinguished himself by maintaining the peace during the coal-miners strike in 1888.[18] In his days tracking bushrangers when on patrol, he employed Aborigines as trackers, being amongst the first in the police force to do so.

Brennan was quite forward in his thinking and attitudes towards Aboriginal people. In his memoir, published after his death, Brennan stated that ‘The Aborigines of New Holland were a remarkable race; but, unfortunately, the treatment they received in the early days was not conducive to their propagation or civilization.’[19] From a contemporary point of view it is interesting to read such liberal thoughts coming from a nineteenth century mind. It is clear that Brennan was also highly respected by his fellow officers. On his death, the Inspector-General noted that

he was one of the most conscientious men that ever joined the police… he was a mounted man throughout his career, and no braver policeman ever faced the troublous times in the back country when bushranging gangs had the selectors in a state of terror.[20]

The contributions of both James Coulter and Martin Brennan to the maintenance and administration of law and order in colonial Australia during the nineteenth century was significant. Coulter tried to implement progress through administrative and magisterial work while Brennan provided practical leadership and training from the saddle. Their contrasting experiences highlight the basis of this argument. Regardless of their backgrounds there is enough evidence to suggest that Irish immigrants made significant contributions to the establishment and progress of law and order in colonial Australia. Although it was a dangerous land for an Irish immigrant to start a new life in the 1800s, it was also a land that offered new beginnings and a wealth of opportunity to those who sought such things.

REFERENCES

[1] Eric Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’ in Irish Historical Studies, 27:107, (1991), p. 232.

[2] Georgina Sinclair, ‘The “Irish” policeman and the empire: influencing the policing of the British Empire-Commonwealth’ in Irish Historical Studies, 36:142 (November 2008), pp 173-187

[3] Ibid, p. 174

[4] Ibid.

[5] Stefan Petrow, ‘Coulter, James (1832–1907)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2005 (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/coulter-james-12862/text23225) (4 April 2017).

[6] ‘Obituary: James Coulter’ in Daily Telegraph, 8 April 1907.

[7] ‘Mr James Coulter. a proper recognition.’ Daily Telegraph, 6 June 1896.

[8] ‘Obituary: James Coulter’ in Daily Telegraph, 8 April 1907.

[9] Stefan Petrow, ‘Coulter, James (1832–1907)’.

[10] Ibid.

[11] ‘Obituary: James Coulter’ in Daily Telegraph, 8 April 1907.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Petrow, ‘Coulter, James (1832–1907)’.

[14] Richards, ‘Irish Life and progress in colonial South Australia’, p. 231.

[15] Ibid, p. 234.

[16] ‘Death of Martin Brennan’ in Truth, 11 Aug. 1912.

[17] M. Imelda Ryan, ‘Brennan, Martin (1839–1912)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1979 (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/brennan-martin-5349/text9045) (4 April 2017)

[18] ‘Death of Martin Brennan’ in Truth, 11 Aug. 1912.

[19] Martin Brennan, Reminiscences of the gold fields and elsewhere in New South Wales: covering a period of forty-eight years’ service as an officer of police (Sydney, 1907), p. 192

[20] ‘Police officer’s death: ex-Superintendent Martin Brennan’, The Sun, 8 Aug. 1912.

*All newspapers accessed via National Library of Australia’s Trove