Painting of Sydney Cove, c. 1800. Source: State Library of New South Wales

On 26 January 1788, a fleet of eleven ships arrived at Sydney Cove, New South Wales. Captain Arthur Philip led the historic voyage from Portsmouth, England, in what became known as the ‘First Fleet’ to Australia. The fleet carried mostly British convicts to the new colony, however, there were other nationalities also present on the fleet. The Irish have been present in Australia from the early days of convictism right through to the abolition of convictism in 1868. Nevertheless, the historiography of the early settlement of Australia predominantly focuses on the roles played by British convicts in shaping Australian culture and society, largely ignoring or downplaying the influence that Irish convicts had on Australian culture and society in relation to education, religion, and leisure. Geoffrey Burkhardt’s work, for example, sets out to trace the first schoolteachers and schools in New South Wales and is rather informative: it lists the first thirty schoolteachers in New South Wales from the period 1788-1810, with the representation of both British and Irish schoolteachers, and both male and female schoolteachers.[1] Despite the mention of Irish schoolteachers in New South Wales, however, the paper only recognises the significance of British educators in the colony, such as the convicts William Richardson and Isabella Rosson, and the free settlers Reverend Richard Johnson and Reverend Samuel Marsden.

Convicts as schoolteachers: Henry Fulton

The first schoolteachers in New South Wales were convicted felons, for the most part, who were sent to Australia from Britain and Ireland to serve their sentences. In the formative years of the penal colony there was a strong desire for the establishment of schools, and due to the insufficient numbers of literate and educated free settlers, well-educated convicts were employed within the education sector. In response to the lack of historiography pertaining to the Irish immigrant teaching experience in colonial Australia, the foundations of Australian education will be examined below by concentrating on the experiences of the first Irish schoolteachers in New South Wales. These experiences will be related to Reverend Henry Fulton, Matthew Hughes, and John and James Kenny.

The Irish rebellions of 1798 and 1803 played a significant role in the outcome of the Irish convict demographic in colonial New South Wales. Most Irish convicts were sentenced to transportation on grounds of theft but in the later years of the eighteenth century and the early years of the nineteenth century, a substantial number of Irish convicts were transported to New South Wales as a result of their affiliation with political organisations like the Society of United Irishmen. The Irish evangelical clergyman Reverend Henry Fulton, for example, was convicted of high treason at a court in Tipperary, Ireland, where he was given a life-sentence to be served in New South Wales.[2] After nearly five months of sailing on the Minerva convict ship, Fulton, along with 232 convicts, arrived at Sydney Cove on 11 January 1800. Fulton was an avid supporter of the United Irishmen and administered the ‘Defender’s Oath’ to local men, which was an illegal practice at this time due to its ties to the radical, revolutionary movement.[3]

Portrait of Reverend Samuel Marsden. Source: Parramatta Heritage Centre

Despite Fulton’s radical political leanings, he triumphed in New South Wales as a clergyman. In October 1800, less than a year after his arrival to the colony, Fulton was appointed as a minister by Governor Philip Gidley King to the Hawkesbury region. Fulton’s position continuously progressed, and in February 1806 he was unconditionally pardoned from his life sentence as a convict.[5] Later that year, Fulton was announced to be the Acting Chaplain of Sydney.[6]

As an emancipated Irish convict, however, Fulton experienced judgement from British evangelicals, most notably Reverend Samuel Marsden. In his letter to Edward Cooke, Marsden evidences the scale of his dislike for Fulton not only because of his convict past, but because of his nationality.[7]

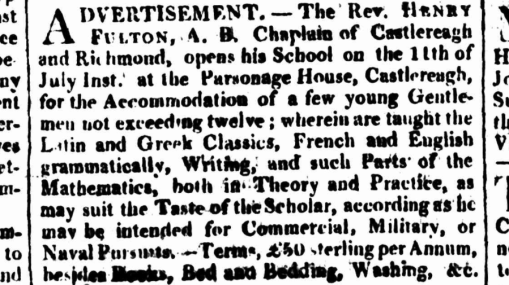

However, even in the face of adversity, Fulton established a school in Castlereagh in 1814 called ‘Castlereagh Classical Academy’, the first secondary school in New South Wales. The school taught male students Latin and Greek, French, English, and Maths, signifying the prestige that Fulton was aiming to achieve for his school.[8] The Academy only operated for eleven years, however.

Newspaper advertisement for Castlereagh Classical Academy, 2 July 1814. Source: National Library of Australia

In 1825, Fulton decided that it was best for the school to close as his demands as Acting Chaplain increasingly took up his time. Nevertheless, the Academy cultivated its students into articulate, cultured men such the Australian poet Charles Thompson. In his poems, Thompson pays homage to his tutor Henry Fulton.[9] Indeed, Fulton was an impressive educator. In Sydney, the founding of the Henry Fulton public school after his death established his legacy as a pioneer educator in New South Wales.

Religious differences: Hughes and Kenny

Significantly, the experiences of Irish educators in New South Wales differed according to their religious affiliation. As previous inhabitants of the mother-country, and as the majority demographic in the penal colonies, British men were the dominant forces in all aspects of societal development. Education in Australia developed not as a governmental foundation but as a religious foundation. Generally-speaking, the British are typically Protestant in their religious identity and beliefs, thus, British Protestant educators believed that good Christian morals would be instilled into students through the immersion of Protestant teaching. It is no surprise then that Reverend Henry Fulton and men of similar religious backgrounds were able to carve out successful careers for themselves in New South Wales.

Sketch of school at Kissing Point. Source: Dictionary of Educational History in Australia and New Zealand

Another convicted Irishman who was able to establish himself as an educator in New South Wales was Matthew Hughes. Hughes was born in 1770 in Down, Ireland. He was a private in the Westmeath military until he was charged of murder and sentenced to life transportation aboard the Britannia convict ship. Hughes was convicted in August 1796.[10] Hughes arrived in Sydney in 1798, and two years after his arrival, he found a job as a schoolteacher at Kissing Point. The building that was going to be used as both a school and a church was erected by Protestant missionaries in July 1800. Governor John Hunter appointed Hughes to the position of schoolteacher. A missionary who went by the name of Hassall visited the school that year and reported that Hughes was effective as a teacher in disciplining the young students and teaching them the Gospel.[11] In 1810, Hughes was appointed government teacher at Windsor. In 1813, he began teaching at Richmond until 1833. Hughes, an Irish Protestant convicted of murder, attained a career level in New South Wales that Irish Catholic schoolteachers could only have dreamed of at this period of time.

John Kenny was a schoolteacher from Carlow, Ireland, who was convicted of robbery. He was convicted in 1791.[12] His younger brother James was also convicted and sentenced to transportation.[13] A few years after their arrival to New South Wales, the Kennys advertised the establishment of a Catholic school in the Sydney Gazette newspaper on 6 October 1805. The school received some assistance from Governor King’s administration, however, with the arrival of Governor William Bligh, the school received no further assistance and closed in 1806.[14] Already at this time, there were a handful of Protestant schools operating. However, all Catholic schools had failed in staying open up until this point. This was not by chance. Educated Catholic convicts such as John and James Kenny faced a disadvantage in the hegemonic Protestant society they inhabited. Reverend Samuel Marsden once said:

‘The number of Catholic Convicts is very great … and these in general composed of the lowest class of the Irish nation; who are the most wild, ignorant and savage Race that were ever favoured with the light of Civilization; men that have been familiar with … every horrid Crime from their Infancy. Their minds being Destitute of every Principle of Religion & Morality render them capable of perpetrating the most nefarious Acts in cool Blood. As they never appear to reflect upon Consequences; but to be … always alive to Rebellion and Mischief, they are very dangerous members of Society. No Confidence whatever can be placed in them’.[15]

A ‘new Britain’?

Portrait of Governor William Bligh. Source: Australian Museum

Such venomous attitudes toward Catholic convicts were not held by all British Protestant leaders, of course. Some, like Governor King, were sympathetic towards the Catholics strive for education centres. Even Governor Bligh, whose arrival saw the closing of the Kennys’ school, granted Catholics the right of mass in 1806.

However, particularly in the years following the 1798 and 1808 Irish rebellions, there were sectarian tensions which permeated in certain Australian ecclesiastical circles as a result. Francis G. Clarke reminds us that ‘we should remember that while Australia was settled by the convicts, it was not primarily settled for the convicts’.[16] In this regard, it becomes obvious why Reverend Samuel Marsden and others like him loathed Irish Catholic convicts. Irish Catholic convicts threatened their idea of an expansion of a ‘new Britain’, a Protestant society, in Australia. Nevertheless, Irish convicts were not entirely defined by their Catholicism. Rather, Irish convicts, both Catholic and Protestant, faced prejudices and challenges in education because of their ‘Irishness’.

REFERENCES

[1] Geoffrey Burkhardt, ‘The first school teachers and schools in colonial New South Wales, 1789-1810’ (Canberra, 2012), available at Australian National Museum of Education, pp 1-3 (http://anme.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ANME_First_Teachers.pdf) (28 March 2017).

[2] New South Wales State Records for Convict Shipping Bound Indents (http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/searchhits_nocopy.aspx?table=Early%20Convict%20Index&id=77&frm=1&query=Surname:fulton;Firstname:henry;Tried_at:tipperary) (23 March 2017).

[3] Con Costello, Botany Bay: the story of convicts transported from Ireland to Australia: 1791-1853 (Dublin, 1987), p. 28.

[5] Copies of conditional and absolute pardons registered, 1791-1867, New South Wales Government Records, Colonial secretary’s papers: special bundles, 4/4486, reel 800, p. 16 (http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/searchhits_nocopy.aspx?table=Convict%20Index&id=65&frm=1&query=Surname:fulton;Firstname:henry;RecordType:absolute%20pardon) (23 March 2017).

[6] Frank M. Bladen, Historical records of New South Wales: King and Bligh, 1806, 1807, 1808 (vol. 6, Sydney, 1898), p. 277 (https://www.archive.org/stream/historicalrecor00walegoog?ref=ol#page/n8/mode/2up) (23 March 2017).

[7] Samuel Marsden to Edward Cooke, quoted in Henry Fulton, ‘Copy of a letter received by Elizabeth Bligh from Henry Fulton’, 1809, SAFE/Banks Papers/Series 42.07, State Library of News South Wales, Transcripts (https://transcripts.sl.nsw.gov.au/content/copy-letter-received-elizabeth-bligh-henry-fulton-1809-series-4207) (19 March 2017).

[8] Henry Fulton, ‘Advertisement, 2 July 1814’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 2 July 1814 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/628941/7181) (26 March 2017).

[9] Charles Thompson, Wild notes: from the lyre of a native minstrel (Sydney, 1826) (http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/pdf/v00007.pdf) (27 April 2017).

[10] New South Wales State Records for Convict Shipping Bound Indents (http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/searchhits_nocopy.aspx?table=Early%20Convict%20Index&id=77&frm=1&query=Surname:hughes;Firstname:matthew) (23 March 2017).

[11] Stephen H. Smith, A brief history of education in Australia: 1788-1848 (Sydney, 1917), p. 17.

[12] New South Wales State Records for Convict Shipping Bound Indents (http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/searchhits_nocopy.aspx?table=Early%20Convict%20Index&id=77&frm=1&query=Surname:kenny;Firstname:john;Tried_at:carlow) (23 March 2017).

[13] New South Wales State Records for Convict Shipping Bound Indents (http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/searchhits_nocopy.aspx?table=Early%20Convict%20Index&id=77&frm=1&query=Surname:kenny;Firstname:james;Tried_at:carlow)(23 March 2017).

[14] Paul Rule, ‘This new land: a history of the Kenny family in Australia: 1793-1956’, Society of Australian Genealogists (1983).

[15] Samuel Marsden quoted in Robert Hughes, The fatal shore: a history of the transportation of convicts to Australia: 1787-1868 (London, 1987), p. 188.

[16] Francis G. Clarke, The history of Australia (Connecticut, 2002), p. 23.