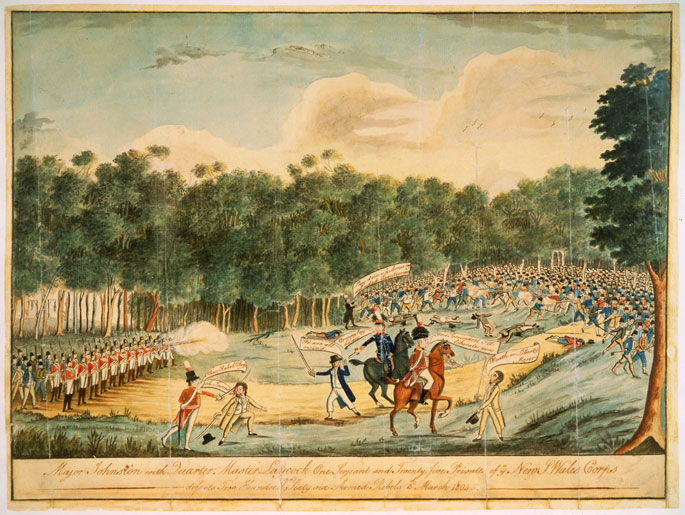

[14][13][20][21]http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/featured/castle_hill_rebellionConvict uprising at Castle Hill, New South Wales, 1804, artist unknown. Source: National Museum of Australia

The mistreatment, oppression and exile of Irish convicts during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries contributed to tensions with colonial authorities and ultimately contributed to the events of 4 March 1804, when a convict rebellion consisting of mostly Irish convicts occurred at Castle Hill, about 30 kilometres north-west of Sydney in New South Wales (NSW).[1] Known now as the Castle Hill rebellion, it was contemporaneously dubbed the ‘Second Battle of Vinegar Hill’ after the Battle of Vinegar Hill which occurred during the Society of United Irishmen’s rebellion in Ireland in 1798. Negative attitudes towards colonial authority had long festered among Irish people who felt marginalised and oppressed by British rule in Ireland, mistreated and often misrepresented within society, sentiments that which continued into the late nineteenth century. In response, groups of Irish people often rose in rebellious action to gain political independence.

The 1798 rebellion in Ireland resulted in many rebels being banished under penal transportation laws and sent to Australia as punishment for their involvement in political crimes. Irish political rebels arrived to Australia in 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1868 as political prisoners. These only made up a small proportion of the convicts transported to Australia. Others were sentenced to banishment for petty crimes of theft; serious crimes like murder and rape usually resulted in death sentences. Approximately a quarter of the convicts that were transported to Australia – 30,000 men and 9,000 women – came directly from Ireland.[2] Australian historical records provide little evidence of armed resistance towards governing authorities; the actions of Irish convicts have achieved considerable prominence as result. On several occasions, Irish convicts were assumed to be plotting against authority, as revealed in an illuminating historical analysis that appeared in a Sydney newspaper, Catholic Press, in April 1927. [3]

Resisting authority

The 1798 Irish rebellion was not the first occasion that Irish people were transported for politically-motivated, or anti-authority reasons. Irish convicts were mostly kept together in punishment settlements to have better control over them as there was a constant fear and suspicion of plotting. From the last two years of the eighteenth century onwards, the infant colony of New South Wales was in a constant ferment, owing to plots and rumors of plots among the Irish exiles, many of whom were political convicts. Having their own distinct language did not aid matters for the authorities as speaking in Gaelic was seen a means of plotting revolt. [4]

During the 1796 transportation voyage of the Marquis Cornwallis, 230 Irish convicts said to be Defenders were transported. The Defenders were a secret society of Catholics in Ireland who were formed as local defensive organisations in response to the failure of the authorities to take action against the Protestant Peep o’ Day Boys who launched night time raids on Catholic homes under the pretense of confiscating arms which Catholics were prohibited from possessing under the terms of the Penal Laws.[5] British authorities described the Irish very desperate characters, who were thought during the voyage to be plotting to seize the ship. This was in fact incorrect as it was a sergeant and two private soldiers who had planned the seize of the ship.

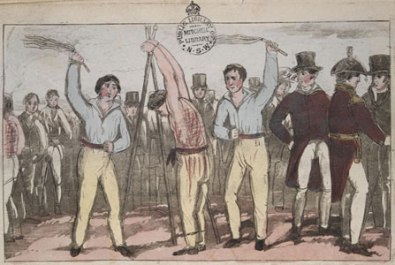

Flogging a convict at Moreton Bay, New South Wales, 1836, artist unknown. Source: State Library New South Wales

In response, Captain Hogan had to put down a mutiny, with the result that seven convicts and a sergeant, one of the mutineers, died of their injuries sustained from flogging, the most common punishment during this period. Women were not allowed to be flogged. In 1833 in NSW approximately 5,800 convicts out of 23,500 were punished by flogging.[6]

Historians suggest that the Irish convicts were relatively less skilled than other convicts which caused conflict and much scrutiny from colonial authorities.[7] The NSW governor from 1795 to 1800 was Vice-Admiral John Hunter, a scholar, sailor and an officer of the Royal Navy. who described the Irish as insolent, refractory and troublesome, adding that it was impossible to obtain any labour from them without the most rigid and severe treatment.[8] It was not until the late-nineteenth century that opinions of Irish convicts shifted at governing level and in the media. In particular, those transported for political crimes or crimes of protest against harsh rural conditions were seen by the twentieth century as people that has been more sinned against than sinners and there was some sympathy for them having been taken from their homes to an alien land.[9]

‘awful criminals and desperate miscreants’?

Political corruption back in Ireland is one of the reasons now given by historians as contributing to the 1804 convict rebellion in colonial Australia, particularly among the higher ranks of society. Many Irish people were transported for offences committed under the Insurrection Act 1796, passed by the Irish Parliament in Dublin to empower the authorities to stamp out the actions of the Defenders and their political allies, the Society of United Irishmen. Originally a liberal, patriotic group agitating for parliamentary reform, the United Irishmen became a revolutionary, republican movement which threatened officials and landed people.

Under the Insurrection Act, magistrates and officers could arrest, punish and sentence people to death but it seems that many random people were ‘shanghaied’ or ‘crimped’ by magistrates solely on suspicion of being Defenders. They received sentences without trial with no form of any legality and sent on the fleet to Botany Bay. Further evidence of suppression was that many of the ships that transported Irish convicts in the late eighteenth century omitted the accounts of the sentence of the prisoners they carried leaving them in the unknown as to the extent of the sentence of the newly transported convicts. This allowed the authorities to exploit the situation and use it to their advantage and have the convicts as essentially slaves whom worked as labours. In 1797, for example, the Britannia arrived at Sydney Cove from Cork with 150 transported ‘convicts’ but failed to deliver any records of conviction.[10]

This type of action heightened the animosity between the Irish convicts and British authorities, as many of the Irish had never actually been convicted, while others had served their time but because of the lack of records, they could not be emancipated as their sentences were unknown. This was a frustrating situation for some convicts who worried that they would never be allowed to return to Ireland. According to some accounts, Irish convicts at Castle Hill Government Farm began to plot a mass escape between 1800 and 1803 but it was not until 4 March 1804 that they implemented their plan.

In 1927, the Catholic Press in Sydney was concerned to counter representations of the rebellion as ‘a mere outburst of characteristic Irish sedition’.[11] Irish convicts had been portrayed as ‘awful criminals and desperate miscreants’ punished for their rebellious activity, and transported in shiploads as defeated rebels, where their hatred of their British masters continued in the Australia penal colony. Contemporary evidence suggests that it was not just the recent rebellious activity in Ireland that riled Irish convicts in Australia. A rebellion had been long expected in Australia and so the reaction of the authorities in 1804 was actually one of surprise that it had not happened sooner in response to their maltreatment; as noted above, convict discipline was harsh.

View of Castle Hill Government Farm, c.1806, Mitchell Library, PXD379-1 f.8. Source: GML Heritage

‘Death or Liberty’

The 1804 Castle Hill convict rebellion was led by Philip Cunningham of Moyvane, north County Kerry, a government stonemason who was convicted for his involvement in the 1798 Irish rebellion; he was also involved in a mutiny on board the convict transport ship, the Anne. [12]. He was key figure in the planning of the rebellion, along with his rebel assistants William Johnston and Samuel Humes.[13] Accompanied by over 200 frustrated armed Irish convicts, their aim was to capture ships and sail to Ireland. The rebels gathered at Castle Hill, calling on other convicts to join them. Their intention was to march from Windsor to Parramatta, and then onto Sydney, gathering recruits along the way to attain a ship to bring them back to Ireland. The Irish rebels were betrayed by an informer Keogh, who told the authorities of the Irish convicts’ plans.

After reports were received, Governor King ordered Major George Johnston to issue a proclamation, ordering martial law for the first time in Australia and a detachment of the NSW Corps were sent in pursuit of the convict rebels.[14] The proclamation stated:

every person who is seen in a State of Rebellious opposition to the peace and tranquility of this colony, and does not give himself or themselves up, within twenty-four hours, will be tried by a court martial, and suffer the sentence passed upon him or them.

This was the first and only major convict uprising in Australia’s history to be suppressed under martial law. The convicts were hunted by the colonial forces until they met on the 5 March 1804 on a hillock nicknamed today Vinegar Hill. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported on the events, giving its most a brief account the events which occurred stating that the Major accompanied with troopers attempted to persuade Cunningham and the rebels to surrender to the mercy that was offered them, in which they refused.[15] Cunningham and the rebel’s response to this was ‘Death or Liberty’. [16]

In a letter to the king describing the events that was published in Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Major Johnston stated how he encouraged the rebel leaders to meet half way to speak with him. When they agreed, Johnston and his troops forcibly drove them into the detachment with pistols at their head.[17] As a result, a short battle erupted but, due to the lack of weapons, the rebellion was put down and many of the rebels fled. In his published letter, Johnston stated:

250 dispersed in every direction, and we have been under the necessity of killing 9 and wounding a great many, the number we cannot ascertain. We have taken 7 prisoners and 7 stand of Arms, and other Weapons; and we are in hopes in our march to the Hawkesbury to pick up some more of them.[18]

While a number of the convict rebels were captured and made prisoners, among them their wounded leader, Philip Cunningham.[19] Cunningham was executed without trial in Windsor.[20] In fact, the convict rebels saw nine of their rebel leaders executed and hundreds punished before martial law.[21] Many of Cunningham’s followers were executed after court martial, seven were sentenced to between 200 and 500 lashes while others were placed in irons or sent north to coal mines as punishment.[22]

It is evident from the historical evidence in primary sources and historical analysis in secondary sources that mistreatment and oppression contributed to the Castle Hill rebellion. The Irish were treated as untrustworthy, devious and were in many cases under constant supervision and suspicion. While the events that took place in Ireland in 1798 contributed to the Castle Hill convict rebellion in 1804, it must be said that if it had not have been for the underlying issues that were present in the new Australian colony of NSW, the rebellion may not have taken place.

Although the rebellion in 1804 was a failure, it highlighted the dissatisfaction felt by many convicts. The Castle Hill rebellion was a result of decades of political issues between the Irish people and the British colonial system that had originated back in Ireland and England but had been brought to the newly found colony, when the Irish were forced under transportation laws into exile to NSW. However, it must be noted that archival records have shown the great majority of Irish convicts who served out their sentences free from trouble.[23]

Significantly, not all those who participated in the rebellion were actually Irish convicts. The Irish-led rebellion was essentially the only means available to other convicts to strike against intolerable oppression . The legal system during this time was extremely flawed, convicts despite their crimes were mistreated, tortured and oppressed. Convicts were sent into exile for minimal offences, while others who were transported without conviction, trial or sentence with no records provided as to how long they were to remain as convicts in this alien land they had found themselves with little hope of ever returning ‘home’.

Memorial to the Battle of Vinegar Hill 1804, Castlebrook Memorial Park, Rouse Hill. Source: Monument Australia

While the Castle Hill rebellion failed, it was an inspiration for future uprisings in Australia such as the Irish-led ‘Eureka Stockade’ at the goldfields in Victoria in 1854, and is memorialised today at Castlebrook Memorial Park at Rouse Hill.

REFERENCES:

[1] ‘Castle Hill Rebellion 1804: Convict uprising known as the Castle Hill Rebellion (or the Battle of Vinegar Hill) put down by New South Wales Corps’, National Museum of Australia, Defining Moments (http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/featured/castle_hill_rebellion) (20 Mar. 2017).

[2] A. G. L Shaw, Convicts and the colonies (1st ed., Ireland, 1998), p. 166.

[3] ‘The Castle Hill Rebellion: Irish Exiles’ Gesture of Despair’ in Catholic Press, 28 April 1927, National Library of Australia’s Trove, (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/107972123?searchTerm=castle%20hill%20convict%20rebellion%20Australia&searchLimits=sortby) (24 Mar. 2017).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Brendan McEvoy, ‘The Peep of Day Boys and Defenders in the County Armagh’ in Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, 12: 1 (1986), pp 123-163.

[6] Charles Bateson, The convict ships, 1787-1868 (1st ed., Glasgow, 1969).

[7] Shaw, Convicts and the colonies.

[8] ‘The Castle Hill Rebellion: Irish Exiles’ Gesture of Despair’, Catholic Press, 28 April 1927.

[9] ‘Irish convicts’, National Museum of Australia (http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/irish_in_australia/family_history/irish_convicts) (1 Apr. 2017).

[10] ‘The Castle Hill Rebellion: Irish Exiles’ Gesture of Despair’, Catholic Press, 28 April 1927.

[11] Ibid.

[12] ‘1804 – The Castle Hill Rebellion – Australia (The Second Battle of Vinegar Hill)’, Stair na hÉireann/History of Ireland (https://stairnaheireann.net/2014/03/04/1804-the-castle-hill-rebellion-australia-the-second-battle-of-vinegar-hill/) (3 Apr. 2017).

[13] Tom Donovan, ‘Some transported rebels of 1798’, Old Limerick Journal (Summer 1998) pp 43-45 (http://www.limerickcity.ie/media/some%20transported%20rebels.pdf) (2 Apr. 2017)

[14] ‘PROCLAMATION – BY PHILIP GIDLEY KING’ in Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 11 Mar 1804, in National Library of Australia’s Trove, (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/626081?searchTerm=convict%20rebellion%201804&searchLimits=l-category=Article|||sortby=dateAsc|||l-state=New+South+Wales) (19 Mar. 2017).

[15] ‘A short account of some of the principal offenders’ in Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 Mar 1804, in National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/626091?searchTerm=castle%20hill%201804&searchLimits=sortby=dateAsc) (24 Apr. 2017)

[16] L. R. Silver, The Battle of Vinegar Hill: Australia’s Irish Rebellion, 1804. (Sydney, 1989), pp 82–86

[17] ‘A letter received by his Excellency from Major Johnston’ in Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 11 Mar 1804, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/626074?searchTerm=castle%20hill%201804&searchLimits=sortby=dateAsc) (24 Apr. 2017)

[18] Ibid.

[19] ‘A short account of some of the principal offenders’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 Mar 1804.

[20] 4 Mar 1804 – Castle Hill convict rebellion’, State Archives and Records NSW (https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/magazine/4-mar-1804-castle-hill-convict-rebellion ) (2 Apr. 2017).

[21] ‘1804 – The Castle Hill Rebellion – Australia (The Second Battle of Vinegar Hill)’, Stair na hÉireann/History of Ireland (https://stairnaheireann.net/2014/03/04/1804-the-castle-hill-rebellion-australia-the-second-battle-of-vinegar-hill/ ) (3 Apr. 2017).

[22] Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: a history of the transportation of convicts to Australia, 1787-1868 (London, 1988), pp 190-94; ‘Castle Hill Rebellion 1804: Convict uprising known as the Castle Hill Rebellion (or the Battle of Vinegar Hill) put down by New South Wales Corps’, National Museum of Australia, Defining Moments (http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/featured/castle_hill_rebellion) (20 Mar. 2017).

[23] ‘Irish convicts’, National Museum of Australia,(http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/irish_in_australia/family_history/irish_convicts) (5 Apr. 2017).