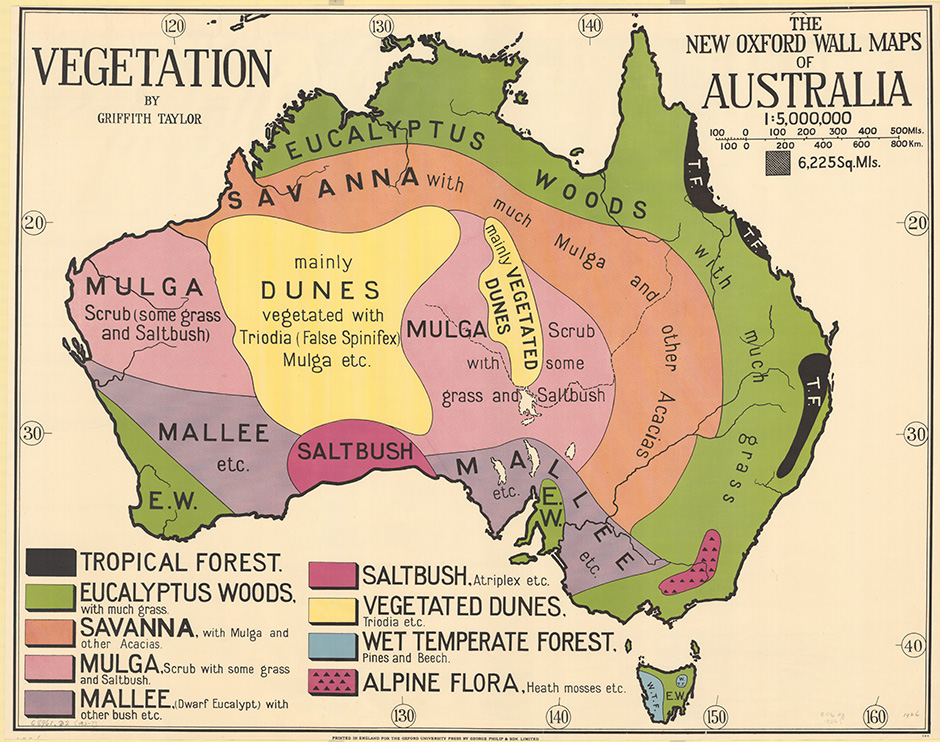

Thomas Griffith Taylor, Vegetation of Australia map, 1920s. Source: National Library of Australia’s Trove

Pluck, industry, energy, ingenuity, determination, and resource.[1] The Irish had been demonstrating these characteristics since they first landed in Australia in 1788 – many involuntarily for reasons including convictism and poverty – and were well settled and integrated by the 1920s when the above map was prepared. Using contemporary newspapers and accounts, the focus here is largely the mixed fortunes of Irish immigrants in the eastern colonies of New South Wales and Victoria by the 1890s. However, each of the colonies were places of mixed fortunes for the Irish immigrants who would settle in the latter half of the nineteenth century.[2] The farming industry produced mixed results for Irish farmers who were selling their produce at markets or fairs, as prices for their goods would fluctuate. Farmers could hold on and refuse to sell for a low price if they knew they could get more at the next fair.[3] For some, this was the only way they could make a profit, especially given the price of and demands for land. Rent and land purchase prices varied greatly depending on the position of the site in question, with more favourable pastures general being on town suburbs where land.[4] Of course, land was not only commodity being purchased and leased by Irish immigrants, but also a means of living for farmers and labourers. Finding other forms of employment was not easy for immigrants, especially for young women who often found themselves in depots and hired out to work as domestic servants.[5]

Land and people

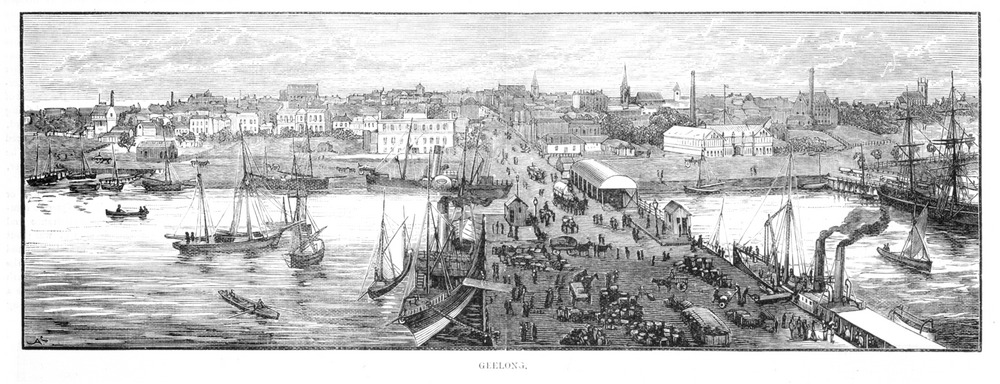

The struggle for to ‘make it’ was not helped by high land prices. An interesting case in point was of Geelong, in Victoria, a town with a large Irish immigrant population. James Frances Hogan, a teacher, journalist, author and politician originally from Co Tipperary,[6] wrote about Geelong as an example of an Australian town where Irish immigrants circumvented the system. Geelong was seen as a revenue opportunity for the government and so sold land at a high rate. In order to combat this, Irish immigrants tended to settle on the outskirts of the town, to obtain land for farming, at a reasonable rate. Price of land in North Geelong was priced at £300 per acre, or £150 per acre in the south. Less favourable land was sold on the outskirts of the town for downwards of £5 per acre, a vast difference from the asking prices of most central land. So, despite the harsh land prices, Geelong became a town of moderate success for the resouceful Irish.

Wood engraving of Geelong, 1886. Source: State Library Victoria

Land would of course continue to be an important asset for Irish immigrants in Geelong, with one suburb, with the appropriate name of Irishtown, later facing an issue with a squatter. Hogan recalled that a man named Frederick Griffin refused a large offer of £50,000 for a five acre estate which later sold for £2,500 because Geelong failed to reproduce the metropolitan status of Melbourne. Hogan also noted that Kilmore was a town of far better wealth for Irish immigrants by comparison with Geelong because it was very early settled by Irish immigrants who claimed the fertile land there for farming while others were focused on urban development. In fact, the land there ultimately proved to be more profitable in ways other than through farming as the Reedy Creek mines would produce gold.[7]

One area where some Irish immigrants succeeded was in trading dairy products; they had varying successes in selling their homemade produce to other communities. One of the most successful of these was butter. The butter industry in the Australia colonies proved very competitive for the ease of its production. In March 1896, the Freeman’s Journal in Sydney reported on the success of ‘Irish butter’ in Ireland citing a Dublin Freeman’s Journal report about a paper presented by Count Moore to the Dairy Association. Arthur John Moore, a wealthy Catholic Irish nationalist MP in Tipperary who was made a papal count in 1879,[8] revealed that in spite of tough competition, Irish butter had ‘topped the market for months’ in Ireland. This was in spite of a lack ‘of uniformity in curing, flavour, and weight, indifferent or untidy packing, and lack of scrupulous cleanliness’. His paper also touched on the enterprise of the railway companies in Ireland for arranging ‘a special tariff for the carriage of agricultural produce in small parcels.’[9] There could not but have been knowledge of this in Australia.

Irish farmers in Australia were using the skills that they had developed over time, back home in Ireland, to earn a wage. Earlier in the century, small farmers would produce and then sell their butter after milking their own cows. By the end of the 1800s, times were changing. Small Irish farmers in Australia would report profiting more by cooperating with other farmers, then continuing the production chain, and making their own butter to sell as a solo effort. Creameries would include many small farmers who would put all their resources together. After selling the butter, they would subtract any depreciation to fixed assets and divide the net profit equally between them. They proved a considerable match for the English producers and, as noted in the Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts newspaper, the only thing preventing them from competing with the Australian and Danish creameries, was their sustainability during the winter months. 23 out of 15 creameries produced 910 tons of Irish butter which sold for almost £99,000 – 1d per poundweight – resulting in a large profit for the small Irish immigrant farmers.[10]

Women at work

As well as a demand for labour in the Australian colonies since the early days of colonisation, there was as a shortage of young females available to marry, keep house and breed with the disproportionate number of men. With Irish workhouses filled to capacity by the mid-1800s on account of the Great Famine, young women, some of whom were orphans, were sent to Australia to offer domestic services to men in rural areas. The hope was for that all selected girls would be educated, but in many cases they were not even trained in simple domestic chores. According to Judy Collingwood, in the case of one Irish workhouse of 150 girls, only 35 knew how to milk a cow, and none of the remaining 115 wanted to learn. They also were unable to do simple tasks like washing clothes and so could not be employed in the roles they were planned to fill in the local countryside. Consequently, many would be employed in more potentially precarious position in urban areas by local business people.

In one case in South Australia, described by Collingwood, inhabitants of a local depot had their rations stopped as it was believed that the Irish girls had been offering themselves on the street and had turned the house into a brothel, due to the poor wages. Things were different in parts of New South Wales, where all girls, once they turned 17, entered into a one year contracted agreement where they would receive payment of between £10 and £15 to act as a house servant, housemaid or nursemaid. Those who were trained would receive between £27 and £31.[11] Rica Erickson has shown that in some cases, girls would offer their domestic services to rich homeowners for no wage in order to receive the necessary experience to find themselves a well-paying job.[12] While these women represented just a portion of the Irish immigrant population, it is interesting to note that the lower classes lived on wages that were at least ten times less than those higher socio-economic status; for example, Tyrone native George Fletcher Moore, Advocate-General in Western Australia, received an annual salary of £200, which was a reduced sum in comparison to other political representatives in other colonies.[13]

Success in Sydney

Through hard work and labour, Sydney would develop into one of the most successful locations for Irish immigrants in New South Wales. Aside from its architectural qualities, the harbour with its fruitful port meant that it would prove to be a town where Irish immigrants could settle into and become successful in. In his 1887 account of the Irish in Australia, James Frances Hogan, explained how once in Sydney, Irish immigrants would become well known through their Catholic origins and input into the local hospital. St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney, was, at this time in 1887, being built to establish a large Irish Catholic stronghold in the town. However, already at this time, St Vincent’s Hospital had a large Irish influence as it was being run by the Sisters of Charity. According to Hogan, the work of the Irish at this hospital was something of great pride to the Irish in the city – patients were treated of their various ailments irrespective of religion – was the Catholic Church’s most proud asset. It had affiliations with St Ignatius’ College through the Jesuit order, along with St John’s College, the University of Sydney and St Joseph’s College.

St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, c.1869-74. Source: State Library of New South Wales

The story of Sydney as a place of successful settlement for Irish immigrants was one long in the making. When gaols become overcrowded in Ireland, they were transported to Australia, Sydney being one of the towns they were sent to. Free convict labour would employ those charged of various offences at home in Ireland, in Sydney until they became free. Those who were sent to Sydney were low in numbers as they had been refused permission to send some convicts here, but when convicts became Emancipists, Sydney was a popular destination to start a new home. As mentioned by Hogan, he witnessed many of these former convicts become liberal and wealthy. When these first generations settled, they often relied on resources and family to be sent from Ireland, which was growing increasingly poor. Disease was widespread and then, as mentioned by Hogan, a number of Irish immigrants were caught out in rum trafficking [14]

However, those who were successful in New South Wales were mostly so due to the quality of the land. Not only was it of perfect quality to rear sheep and farm but like in Victoria in the 1850s, it was home to a short-lived gold rush meaning that the population of immigrants, Irish included, would increase in urban places such as Sydney.[15] The socio-economic experience of Irish immigrants thus varied depending on where and how they settled once they arrived on the Australian continent. Farmers had varied luck when it came to selling their produce at the markets and when purchasing land at auctions. It was not always a positive experience especially for young orphan girls who received a small wage by comparison with men who went on to hold prominent government positions. There is always evidence to be found, however, of those characteristics distinctive of Irish immigrants: industry, energy, determination, resource, pluck and ingenuity.

REFERENCES

[1] Diggers Gazette, 1, no. 14 (1 June 1920), p.41, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-13191405/view?partId=nla.obj-20952003)

[2] ‘Irish convicts’, National Museum Australia, Exhibitions: Not Just Ned, Irish family history (http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/irish_in_australia/family_history/irish_convicts) (8 Apr. 2018)

[3] Diggers Gazette, 1 June 1920

[4] James Frances Hogan, The Irish in Australia (London, 1887), pp 100-107, State Library of Victoria (http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/271946)

[5] Judy Collingwood, ‘Irish workhouse children in Australia’ in J. O’Brien and P. Travers (eds)., The Irish Emigrant experience in Australia (Dublin, 1991), pp 46-61

[6] John R. Thompson, ‘Hogan, James Francis (1855–1924)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 4 (1972), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hogan-james-francis-3780/text5973) (13 May 2018).

[7] Hogan, The Irish in Australia, pp 100-107.

[8] ‘Arthur John Moore’ The peerage: A genealogical survey of the peerage of Britain as well as the royal families of Europe (http://www.thepeerage.com/p22772.htm#i227713)

[9] Freeman’s Journal, 28 March 1896, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/111101058)

[10] Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, 26 March 1893, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/125891374)

[11] Collingwood, ‘Irish workhouse children in Australia’, pp 46-61

[12] Rica Erickson, ‘Friends and neighbours: the Irish of Toodyay’ in B. Reece (ed), The Irish in Western Australia, (Nedlands, 2000), pp 49-58

[13] James Cameron, ‘George Fletcher Moore’ in B. Reece (ed), The Irish in Western Australia, (Nedlands, 2000), pp 21-34; Alfred H. Chate, ‘Moore, George Fletcher (1798–1886)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2 (1967), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/moore-george-fletcher-2474/text3321) (13 May 2018).

[14] Hogan, The Irish in Australia, pp 173-177

[15] Ibid, pp 171-174