Irish immigration across the world, and specifically to Australia, has been discussed by Tim Pat Coogan in his Wherever Green is worn: the story of the Irish Diaspora.[1] Coogan highlights how the discovery of gold was one of the main factors that changed attitudes towards Irish immigrants in Australia and writes in depth about life on the gold fields and how the Irish were welcomed. His book provides an excellent insight into the Irish immigrant experience and context here for exploring how the discovery of gold in Victoria was a major pull factor for the Irish.

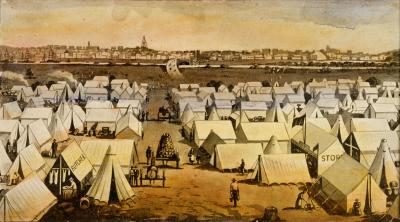

De Gruchy & Leigh, lithograph of a canvass town set up to accommodate the large numbers of people coming to Victoria in search of gold, c.1855 Source: State Library of Victoria’s Pictures Collection

The following piece will provide an analysis of the Victorian gold rush and highlight the effect it had on the economy. More specifically, this essay will look at Irish immigrant James Esmond and his role in developing the Australian economy in the nineteenth century. By using James Esmond as a case study and drawing on relevant primary sources, this essay highlights how the Irish socio-economic experience was different for different Irish people. In the case of James William Esmond from County Wexford it was one filled with success – for a time.There exist many disputes as to whether the Irishman James Esmond was the first (colonist or white man) to discover gold in Victoria. For example, Louis R. Cranfield, in his biography of James William Esmond, argues that his claim to be the first discoverer of gold is false.[2] However, The Geelong Advertiser, on 7 July 1851, describes the first recording of gold found in Victoria:

the long-sought treasure is at length found, Victoria is a gold country, and from Geelong goes forth the first glad tidings of the discovery. Mr. Esmond arrived in Geelong on Saturday with some beautiful specimens of gold [3].

Additionally, backing up the claim that Esmond was the first to find gold, The Argus published the next day, reported that, ‘Mr Esmond came into Geelong on Saturday last with several pieces of quarts and some gold pieces…. [and] there is not the slightest doubt of its being the real thing,’[4]. Additionally, later newspaper accounts have all referred to James Esmond as being the first discoverer of gold in Victoria.[5]. Whether or not James Esmond was the actual first discoverer of gold in Victoria, he was the first to uncover workable gold-field in Victoria which resulted in the fast expansion of Victoria and its economy. In 1853 and 1854 a council was established in Victoria to give rewards to individuals for discoveries in the gold fields. The claims of James Esmond were legitimated by the Legislative Council of Victoria who ‘in acknowledging Mr Esmond’s claim upon the gratitude of the colony, voted him the sum of £1,000.’[6]

Gold fever!

The long nineteenth century was one dominated by the discovery of gold. With this discovery came higher levels of migration to the colonies which led to the development of great cities. Prior to the discovery of gold in New South Wales the world was already filled with gold fever. The 1848 discovery of gold in California initiated the first global gold rush. Although the discovery of gold was met with great excitement in Britain, ‘most prospective diggers held back’ as put by Michael Evans in his Gold Fever! Life on the Diggings 1851-1855.[7] The reason for this simply was that the route to California was a long and dangerous one. Additionally, the digging sites were portrayed as hellholes. However, the discovery of gold in the colonies of Australia was to yield a different result. Evans notes: ‘Here, few of the deterrents to Californian migration applied. British law was well established and, despite the lingering convict taint, early reports described the diggings as peaceful and orderly’[8].

Migration to the colonies was increased through these discoveries of gold. Prior to this, people and organisations had been trying to push for migration to the colonies. For example, the Bountry Scheme was created in 1835 and ran until 1841 in an attempt to attract young couples and single women. Now, with the discovery of gold, these same people were easily pushed towards migration. The novelist Charles Dickens even published information about the goldfields and stories of success in his ‘Household Words’. Now, with Hargreaves’ discovery of gold in Australia, it seemed as nearly every ship arriving carried individuals who sought to make their fortune. The Victorian gold rush began in 1851 and, as highlighted by Peter Davies et al ‘was part of a global pattern of mining booms that punctuated the nineteenth century’[9].

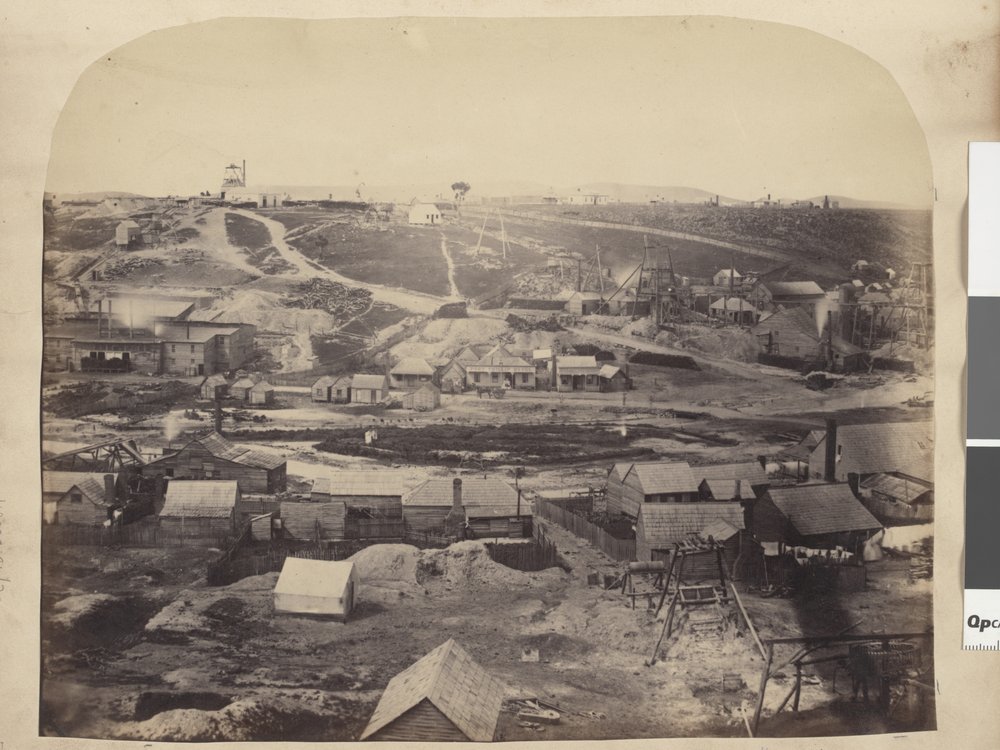

Richard Daintree, photograph of gold mining settlement Clunes, Victoria. Source: State Library of Victoria

‘Civil Jim’: James William Esmond (1822-1890)

The titles ‘father of gold mining in Australia,’ and ‘gold discoverer’ are held by James William Esmond who was contemporaneously considered to be the first person to discover gold in Victoria. [10] James Esmond was born in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Ireland in 1822. His father was a merchant. Esmond was a colonist who as a boy displayed a substantial interest in geology. He migrated to Port Philip in 1840 where he drove a weekly mail coach between Buninyong and Burnt Bank, now called Lexington. In 1887, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate newspaper described how, ‘although a very young man, he had already occupied his position for several years, and in all the country roundabout he was familiarly known as under the complimentary title of ‘civil Jim’.[11] He was described as being adventurous and courageous and it was no surprise that in 1849, when everyone was talking about the gold to be found in California, he quit his job and made his way to the gold fields there. However, Esmond arrived too late to make any real profit off the gold mines of California and instead worked as a supervisor on the diggings.

While working on the gold mines in California Esmond reportedly ‘observed a similarity between the soil and surroundings of that country and those of Clunes in Victoria.’ With this in mind, he made his way back to Port Philip to examine the area of Clunes for gold – and was successful. Interestingly, it is reported that Esmond shared the journey from California to Victoria with a man whose name would soon become the most known in Australia’s gold mining history, Edward Hammond Hargreaves.[12] It was reported in The Leader that Hargreaves ‘discovered gold in New South Wales, and … received £10,000 from the government of the mother colony as a reward for his successful explorations.’[13]

The period of Esmond’s discovery was one characterised by gold discoveries at Ballarat and an increase in population in the nearby cities like Melbourne. Esmond would later go on to take part in the revolt known as the Eureka Stockade which was a rebellion in 1854, instigated by the then gold miners of Victoria. The rebellion was the result of a build up of civil disobedience in Victoria as the miners of the colony objected to the expensive miner’s licence. Eventually in 1865, Esmond set up his own gold mining company; however, the company was unsuccessful, and he had to sell it. Although Esmond’s early life was one filled with glory and success on the gold fields, he later struggled in life. It was reported in 1890 by The Leader that ‘he died poorly.’[14] He suffered from Bright’s disease (chronic inflammation of the kidneys) and was essentially broke with no money. Around 1884 he applied to the government of the colony of Victoria to receive for money for his contributions towards the success of the colony but was unsuccessful. Although his later life was a bleak one and he died in poor conditions, the ways that his community felt about him and his discoveries is evident in their descriptions in The Ballarat Star: ‘he more than any other man has helped [the colony] to the headship of that happy sisterhood of States.’[15]

The entrepreneurial spirit of Victoria

Photograph of a monument crediting James Esmond with the ‘earliest media announcment of payable gold in Victoria.’ Source: Monument Australia

The early years of Irish immigration to the Australian colonies were characterised by prejudices held against them. Throughout the colonies there was a sense of tension between British or English colonists and some of the Irish. However, as argued by Tim Pat Coogan , ‘gold was one of the great factors in improving conditions. Gold changed Australia and the Irish.’[16] In the year 1851, the state of Victoria experienced the discovery of gold, thanks to Esmond and others like him, and all the socio-economic benefits that followed. During this period, Victoria, a new colony from 1851, had some of the ‘richest shallow alluvial goldfields the world had ever seen.’[17] As a result of this, the population of the colony dramatically increased from 77,000 to 540,000 in 1861.[18] The story of James William Esmond searching for success in the gold fields is just one of many as thousands of Irish made their way from their homeland in search of gold.

It is important to note that the Irish going to America and the Irish going to Australia were very different. Patrick James O’Farrell in his The Irish in Australia, argues how, ‘the balance of research now strongly favours the proposition that the United States not only got the most of the Irish but the worst … In Australia, in contrast, the emancipated convict Irish soon developed modest but significant entrepreneurial qualities; very few famine refugees came to Australia; and its mass Irish population came from the 1850s to the 1890s in search of gold, land, fortune and adventure.’[19] This Victorian gold rush brought in many of these new ‘entrepreneurial’ immigrants who too sought to make their fortune, as James William Esmond did. This influx of immigrants led to the development of the colony of Victoria and made cities like Melbourne to be some of the greatest in the whole of the Australian continent.

As David Fitzpatrick had claimed, the ‘Irish-Australians were unique in their ordinariness’.[20] The story of James William Esmond is one of how an ordinary Irish immigrant made his mark on the development of Victoria’s economy. Through determination and hard work, he was able to make something out of his immigrant experience and his geological and mineral discoveries led to the socio-economic transformation of the colony of Victoria.

REFERENCES

[1] Tim Pat Coogan, Wherever Green is worn: the story of the Irish Diaspora (New York, 2000).

[2] Louis R. Cranfield, ‘Esmond, James William (1822-1890)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 4 (1972), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/esmond-james-william-3485)

[3] Geelong Advertiser, 7 July 1851, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/91920276?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FG%2Ftitle%2F284%2F1851%2F07%2F07%2Fpage%2F8144905%2Farticle%2F91920276#)

[4] The Argus, 8 July 1851, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4778972?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FA%2Ftitle%2F13%2F1851%2F07%2F08%2Fpage%2F505723%2Farticle%2F4778972)

[5] The Age 8 November 1855; The Ballarat Star, 7 August 1884.

[6] The Age, 8 November 1855, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/154867147?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FA%2Ftitle%2F809%2F1855%2F11%2F08%2Fpage%2F18211626%2Farticle%2F154867147)

[7] Michael Evans, Gold Fever! Life on the diggings 1851-1855 (Canberra, 1994), p. 4.

[8] Evans, Gold Fever!, p. 5.

[9] P. Davies, J. Turnbull and S. Lawrence, ‘Remote sensing landscapes of water management on the Victorian goldfields, Australia’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 76 (2016), p. 50.

[10] The Leader, 6 and 13 December 1890.

[11] Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 5 March 1887.

[12] Bruce Mitchell, ‘Hargraves, Edward Hammond (1816–1891)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 4 (1972) National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hargraves-edward-hammond-3719/text5837) ( 22 May 2018).

[13] The Leader, 6 December 1890.

[14] The Leader, 13 December 1890.

[15] The Ballarat Star, 7 August 1884.

[16] Coogan, Wherever Green is worn, p. 153.

[17] Davies, Turnbull and Lawrence, ‘Remote sensing landscapes of water management on the Victorian goldfields, Australia’, p. 50.

[18] G. Serle The Golden Age: A history of the colony of Victoria, 1851-1861 (Melbourne, 1968), p.369.

[19] Patrick O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia (Kensington, 1987), p.63.

[20] David Fitzpatrick, ‘Irish emigration in the later nineteenth century’, Irish Historical Studies, 22 (1980), p.137.