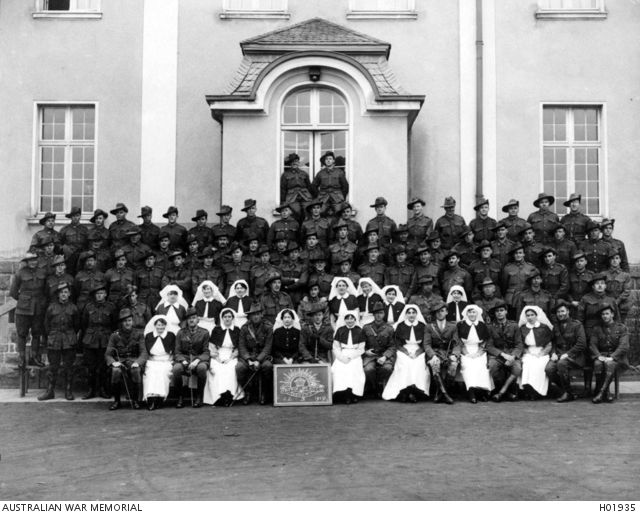

No.3 Australian Casualty Clearing Station group photograph of nursing staff and soldiers, Germany 1919. Source: Australian War Memorial

Australia’s role in World War One is often seen as a milestone in the creation of the Australian national identity and character, which embraces mateship, bravery and anti-authoritarianism.[1] The concept of Australian identity, in particular, within the context of World War One has been shaped by accounts of the actions of the Australian Military Forces, with little reference to the nurses who aided them. Historians like Charles Bean, for example, associated the creation of the Australian national identity with the ANZAC’s heroism during the Battle of Gallipoli. The nation’s sacrifices at Gallipoli then have tended to dominate the discourse of Australia’s role in World War One. As Australia attempted to make its international mark, it adopted a collaborative, altruistic and, diversified ideology, and mateship became a signifier for ‘Australian-ness’. The idea of mateship has been primarily used to describe relationships between and images of the Australian soldiers who fought during the war.

However, a similar sense of solidarity and commitment was displayed by the various nurses working in Australian services during the war and was increasingly evident as they began to adopt a collective Australian national identity. While the soldiers shared a collective mission to fight for their nation, the nurses worked together to treat the wounded and sick in similar conditions. The role of Irish nurses enlisted in Australian nursing services is often addressed by historians as a collective experience due to the limited numbers. There are few accessible accounts of Irish nurses in Australian service although there are references to individual Irish nurse’s experiences during the war. Jeff Kildea has briefly discussed Kathleen Power’s nursing career yet the focus was primarily on the soldiers’ experience.[2] Kristy Harris has written extensively on the Australian nurses during World War One but her work overlooks the experience of the Irish women who served alongside the other ANZAC nurses.

Irish nurses in Australian service

The Irish women who enlisted in nursing services in Australia only constituted a small minority making it difficult to separate their experiences from the majority of Australian women. Harris has also highlighted the increasing difficulties of identifying women who were enlisted in organisations outside the Australian Army Nursing Service such as the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service reserve. The difficulties of negotiating records on Australian nurses in these services means limited documentation of Irish nurses.[3] Harris has criticised military historians for largely overlooking the contribution of the Australian women during the war; Bean, for example, received criticism for his lack of reference to the AANS. However, it is now known that the publishers removed chapters which contained information on the nursing services.[4] After submitting his draft of his volumes Bean was pushed by the publishers Angus and Robertson to remove chapters and numerous reference to the AANS. While the original draft mentioned various incidents between surgeons and matrons and highlighted the camaraderie between the nurses and soldiers and the nurses, the publishers believed these descriptions detracted from the men’s experiences.

From the early stages of immigration to the Australian colonies, the stereotype of poor Irish women dominated the discourse of Irish female immigrants. The myth of poor Irish women working as prostitutes was perpetuated by early convict transportation to Australia where women earned the reputation of the promiscuous lower class.[5] Female orphan immigration from Ireland was widely disapproved of by colonial society in the 1800s. Although there was a need for gender balance in the colonies, many colonists suggested that the Irish orphans which were being sent were a threat to the future bloodlines of the colonies. An editorial published in The Argus in 1850, for example, protested heavily against such orphan immigration strategies insisting that these, predominantly Roman Catholic, Irish orphans were ‘little better than heathens’ and suggested that their ‘money ought be expended upon the rosy cheeked girls of England’.[6] The Irish women who joined the Australian nursing services broke the shackles of the long standing stereotypes to become a part of a collective, imperative force in the Australian story.

The Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), established only one year after the federation of Australia, was one of the new nation’s most notable nursing services during the war. In July 1902, nursing services from each state in Australia joined together to create the AANS, and was made up of volunteer trained nurses who were to serve in times of national emergency.[7] The AANS was the largest nursing service in Australia during the war with numbers exceeding 2,286 nurses who served overseas.[8] Of the nearly 2,500 nurses enlisted, the Irish ANZACs Database has records for thirty who are Irish born. Fifteen of these thirty Irish women in the records held positions as sisters in their respective units, a promotion above a staff nurse.[9] Jane Elizabeth Borbridge Molloy from Armagh, achieved the highest position within a nursing unit as Matron.[10]

Alicia Mary Kelly (1874-1942)

Alicia Mary Kelly photographed for Table Talk magazine, 1910. Source: National Library of Australia’s Trove

The evidence of Irish nurses progressing through the ranks within the service indicated a system based on ability and work ethic. Within the AANS, an individual’s ethnicity did not hinder her ability to progress and highlighted a mutual respect among the women. Alicia Mary Kelly was one such Irish nurse whose achievements during the war were lauded not only among her fellow Irish but also by her Australian comrades.

Alicia Mary Kelly was born on the 16 September 1874 in Oughterard, Co. Galway, Ireland. In 1891, Bridget Jane Kelly along with four of her children, including young Alicia, had boarded the Oroya and immigrated to Australia.[11] In 1910, Alicia finished her nurses training in the Royal Melbourne Hospital. Alicia was an experienced nurse working in a private hospital and was a member of the Royal Victorian Trained Nurses Association. On the 29 March 1915 in Melbourne, Alicia enlisted in the AANS.[12] Alicia became highly decorated and, despite her Irish origins, held one of the most impressive nursing careers during the war. Alicia was appointed to the No. 1 Australian General Hospital (1AGH) and served in Egypt to treat the soldiers from the front in the Battle of Gallipoli.

In April 1916, Alicia along with 1AGH were transferred to France where records show she was promoted from staff nurse to sister.[13] The most significant event in Alicia’s career came when she was transferred to No.3 Australian Casualty Clearing Station (3ACCS) in Ypres. The station was close to the Western Front where for five days they experienced severe air raids from the German forces. During the final day of shelling the nurses were ordered to retreat to safety, but Alicia refused to leave her patients. The quick-thinking nurse used enamel basins as helmets to cover the wounded soldiers’ heads; although the helmets were of no protection it boosted the morale amongst them. The bravery of Alicia was accounted for by Matron E.A Conyers in the Inglewood Advertiser which reported

‘her quiet courage and clever resourcefulness enabled these nerve-shattered men to come through the ordeal of bombardment with cheery confidence’.[14]

Sister Alicia Mary Kelly was one of seven Australian Nursing Service nurses to receive a Military Medal awarded by His Majesty the King for ‘conspicuous gallantry displayed in the performance of her duties on the occasion of hostile air raids on Casualty Clearing Station in the Field’.[15] The accomplished nurse was later awarded a Red Cross Decoration for her valuable service during the war. Kelly’s role during the war shows the level of unity expressed within the nursing services; she was regarded highly among her colleagues and the Australian nation accepted her as one of their own in presenting her with medals as an Australian nurse. Alicia’s experience was extraordinary but there is no evidence to suggest that the treatment she received differed to that of her fellow Irish nurses.

Discrimination and assimilation

Like the Irish immigrant women in colonial Australia, the indigenous peoples had long faced harsh, consistent – and worse – discrimination; they were not counted as citizens, were forbidden to vote in elections or enlist in the armed forces. In May 1917, however, due to an increased need for soldiers, the Defence Act 1909 was modified to allow ‘half caste’ Aboriginal men enlist in the Australian Imperial Forces.[16] Those who joined were seeking a means of attaining increased equal rights for indigenous people – the war made this seem like a possibility. As the soldiers fought shoulder-to-shoulder on the battle field, ethnicity was forgotten and respect among the men appears to have been mutual. Jessica Horton has argued that the ideology behind military service for the Aborigines was driven by a hope for inclusion in society by means of national service, personal sacrifice and imperial loyalty.[17]

Private Douglas Grant pictured (left) with fellow soldiers of the 13th Australian Infantry Battalion, 1916. Source: Australian Museum

After the war unfortunately this brief sense of equality reverted back to the pre-war discrimination. Aboriginal war veteran Douglas Grant’s participation and notoriety from the war became a promotion for assimilation for the indigenous people. However, the Aborigines themselves did not agree with the concept.[18] Discrimination continued for the Aborigines, only partly owing to their refusal to assimilate with what they considered to be a British colonial imposition. While not directly analogous, there is no evidence to suggest that Irish ANZAC nurses articulated their national identity so strongly that it threatened their assimilation, even while fighting a war on the side of the British empire. They assimilated and were accepted as ‘Australian’. The need for acceptance and inclusion in was probably not as significant for Irish women immigrants in the early twentieth century as it had been for previous generations but it may have played a factor in their decisions to join the military nursing services. Unlike the Aborigines, the Irish nurses after the war maintained their positions within nursing services back in Australia and solidified themselves as equal citizens.

The Irish nurses of the Australian military nursing services hold a place then in history alongside their ANZAC counterparts. World War One created a mutual solidarity among those involved, ensuring reliance and camaraderie, as they all worked towards helping the wounded. Irish nurses in these services were not seen as ‘lesser’ or as ‘outsiders’ but fellow nurses and Australians embracing what is now considered a staple characteristic of Australian Identity. The Australian Army Nursing Service pledge, introduced during World War Two, remains an expression of the necessary solidarity encouraged within the service during times of conflict. Those who enlisted in the AANS vowed to ‘work in unity and comradeship’ with their fellow nurses, which reflects the ideology of solidarity that characterises Australian-ness to this day. [19]

Irish nurses worked shoulder-to-shoulder with the other ANZACs and although their experience is documented by historians primarily as a collective, the bravery and contribution some made should not be diluted in history. It is argued within the context of the Aboriginal experience that historical records oversimplify their individual and cultural identities.[20] However, the Irish nurses had the autonomy to choose to become a part of the Australian nation’s fight on the side of the British empire and its allies. The individual contributions and achievements of the Irish women within the Australian nursing services undoubtedly helped to maintain the legacy of inclusivity under conditions of conflict. Australian sociologist Anthony Moran argues that national identity is important when establishing solidarity – in the cases of the Irish ANZAC nurses, this identity was now more Australian than Irish.[21]

REFERENCES

[1] Anthony Moran, ‘Multiculturalism as nation-building in Australia: inclusive national identity and the embrace of diversity’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34 (2011), pp 2153-2172: 2156.

[2] Jeff Kildea, ‘Irish ANZACs: the contribution of the Australian Irish to the ANZAC tradition’, Paper delivered at Parliament House Sydney (2013), pp 1-17. Jeff Kildea website (https://jeffkildea.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Irish-Anzacs-2013.pdf)

[3] Kristy Harris, ‘Girls in grey: surveying Australian military nurses in World War I’, History Compass, 11 (2013), pp 14-23.

[4] Ibid, p. 15.

[5] Joy Damousi, ‘Chaos and order: gender, space and sexuality on female convict ships’, Australian Historical Studies, 26 (1995), pp 351-372

[6] The Argus, 24 January 1850, ‘Female Orphan Immigration’, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4771328?searchTerm=argus%2024%20January%201850%20irish%20orphans&searchLimits=l-title=13)

[7] ‘Australian Army Nursing Service, 1902 – 1948’ , The National Foundation for Australian Women (NFAW) in conjunction with The University of Melbourne, The Australian Women’s Register, (http://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/AWE0408b.htm)

[8] Kristy Harris, ‘Girls in Grey: surveying Australian military nurses in World War I’, p. 14.

[9] Service Records for Irish Nurses 1914-1920, Irish ANZAC Database, (https://repository.arts.unsw.edu.au) (1 Apr. 2018)

[10] Australian Imperial Force Service Records of Jane Elizabeth Borbridge Molloy, 1 Oct. 1915, Irish ANZAC Database, B2455/7980870, p.13.(https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=7980870&S=1)

[11] Suzanne Welborn, ‘Kelly, Alicia Mary (1874-1942)’, in Australian Dictionary of Biography, 9 (1983) available at: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/kelly-alicia-mary-6915 (2 Apr. 2018); Debbie McCauley (2013) ‘Alicia Mary Kelly (1874-1942)’ Tauranga City Libraries, Tauranga Memories:Remembering War (https://perma-archives.org/warc/LN4G-C89B/http://tauranga.kete.net.nz/remembering_war/topics/show/1536-Alicia-Mary-Kelly-(1874-1942)

[12] Australian Imperial Force Service Records of Alicia Mary Kelly, 29 Mar. 1915, Irish ANZACs Project, B2455/3010279, pp 1-21 (http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=3010279)

[13] Ibid. p.6

[14] ‘Nurses Work Appreciated’, Inglewood Advertiser, 15 Jan. 1918, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/121043709?searchTerm=inglewood%20advertiser%2015%20january%201918&searchLimits=l-australian=y)

[15] Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 14 Feb. 1918, p.284 available at: (https://www.legislation.gov.au/file/1918GN19)

[16] Jessica Horton, ‘’‘Willing to fight to a man”: The First World War and Aboriginal activism in the Western District of Victoria’, Aboriginal History, 39 (2015), pp 203-222.

[17] Ibid, p. 204.

[18] Noah Riseman, ‘Aboriginal Military Service and Assimilation’, Aboriginal History, 38 (2014), pp 155-178.

[19] ‘Australian Army Nursing Service, 1902 – 1948’, The National Foundation for Australian Women (NFAW) in conjunction with The University of Melbourne, The Australian Women’s Register (http://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/AWE0408b.htm)

[20] Philippa Scarlett, ‘Aboriginal service in the First World War: identity, recognition and the problem of mateship’, Aboriginal History, 39 (2015), pp 163-81: 163.

[21] Anthony Moran, ‘Multiculturalism as nation-building in Australia: inclusive national identity and the embrace of diversity’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34 (2011), pp 2154.