Line image of a game of hurling, Melbourne, 1906. Source: Victorian Collections Partnership

There is a documented presence of hurling in colonial Australia dating from the 1840s with possibly the earliest date of reference dating back to St. Patrick’s Day in 1843.[1] Hurling was much more than just a sport to the Irish diaspora in Australia as it represented more than a pastime to those that played the game; equally to those that spectated. It was a means by which the Irish diaspora maintained a cultural bond with their homeland and as it became popularised in Australia by the continued emergence of Irish communities, it became a crucial instrument of identity of perceived ‘Irish-ness’.[2] Hurling played an important part for the Irish in the Australian colonies, specifically Victoria and New South Wales. It gave them a link to the homeland as well as a link to their history, to the tales and myths of Cúchulainn and Fionn Mac Cumhail that were part of popular history in Ireland down through the generations. It gave them a sense of home and thus was played with vigor and ferociousness.

Throughout the nineteenth century scores of hurling matches have been reported in the newspapers, with advertisements for upcoming games as well as match reports detailing the events and a general idea of attendances .[3] The interest was there, not just from the Irish diaspora but the other nationalities in the colonies at the time; it was a game never seen before by some and thus created intrigue. Such was the popularity among the diaspora that interest and influence soon followed from the Roman Catholic Church and some apprehension on the part of the colonial authorities. Large groupings of Irish people, particularly Catholics, were met caution by authorities and as such hurling in the colonies was monitored closely to ensure that peace remained. Through the analysis of primary sources relating to hurling in the colonies and the Catholic Church influence that accompanied it, it will be evident that the relationship between sport, religion, and colonial authority was diverse and complex.

Leading the way from ‘down under’

Described as an ‘honest game’ in the Sportsman newspaper, the dominant sports publication in Melbourne, Victoria between 1882 and 1904, hurling was admired by those who witnessed the spectacle.[4] For this reason it was held in high esteem not just from by Irish diaspora but by immigrants from other countries and those born in Australian who witnessed well-attended games; some reports suggested that crowds could range from a few hundred people to close to 5,000.[5] Scores of newspaper articles exist that document the many hurling matches that took place throughout the Australian colonies, particularly in New South Wales in its formative years and Victoria in the latter part of the century.

As well as extensive reports from hurling matches, the Sportsman also contained advertisements for upcoming games and opinion pieces including one simply titled ‘Hurling’, published on 15 October 1890. This piece examines not only the game play but also other aspects including the location and the particulars, wherein it alludes to dimensions of the field of play, numbers present on both teams as well as the lack of organised rules. It even gives insight and constructive criticism as to how the game can be improved and developed in order for the game to gain significant popularity in the state of Victoria.[6] This feature is not isolated to this article as Patrick Bracken has highlighted, stating that the Australian newspapers, particularly the Sportsman, were an important medium for transmitting leisure and sporting news to the general public. This is evident in the sheer frequency at which fixtures, and times for challenge matches appeared in the press conjointly with subsequent match reports relating to said challenge matches.[7]

The anonymous author of the ‘Hurling’ piece in 1890 seemed to have good knowledge of the game of hurling at this time and passed comment on the competitiveness and ferociousness of a match between Ararat and Stawell. He offered personal comments on the game, criticised the players and some of the actions on show: ‘every device that could spoil the dash that our players are noted for, was resorted to in order that a victory may be obtained by hook or crook’. He questioned if ever such an exhibition of hurling had been witnessed in Victoria.[8] Moreover the author alludes to the fact that there were laws and rules surrounding the game of hurling at this time period; published firstly by Henry Ives in the Bendigo Advertiser, September, 7 1887, seven years BEFORE the official establishment of the Gaelic Athletic Association (and rules for hurling) in Ireland, the origin of the age old sport.[9]

As in the arena of women’s suffrage, the Australian colonies were once again proving more progressive than their British Isles counterparts, this time with regard to the official rules of Irish sports and pastimes, which were published in Ireland after the establishment of the the Gaelic Athletic Association at Hayes’ Hotel, Thurles, County Tipperary in 1884. Nevertheless, the Australian hurling rules played an important role in the context of hurling in Ireland, as they not only inferred continuity and progression but offered clear evidence of the transnational nature of sport in the Victorian era.[10] Thus, thousands of miles and generations apart, the Irish diaspora were still impacting culture and leisure, not only in their new home in Australia, but also back ‘home’ in Ireland.

The ‘innocent and manly game of Old Ireland’

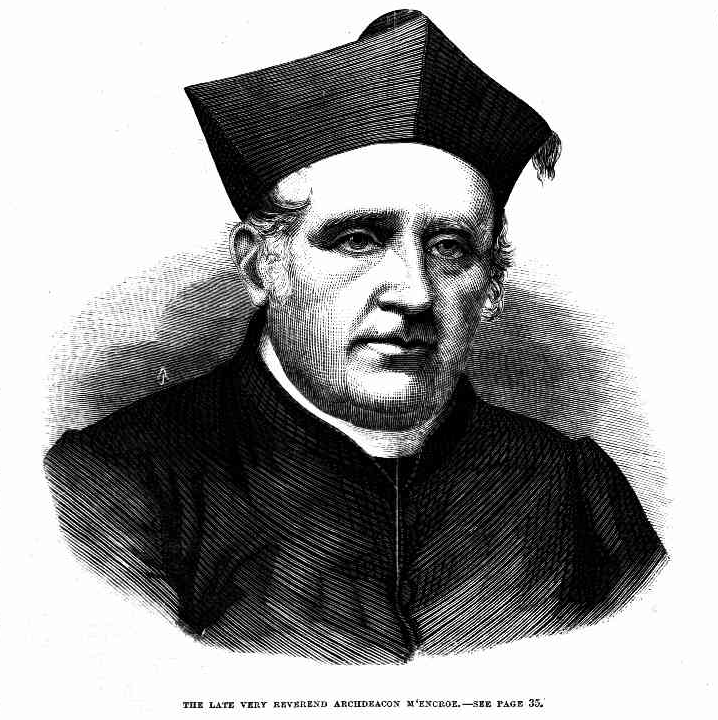

Dating back to the earliest reports of hurling in Australia in the 1840s, the prominence and popularity of hurling among the Irish diaspora appears to have been aligned with Catholic church influence and interest. An article in the Morning Chronicle in 1846 reported a sermon by Very Rev. John McEncroe in which he mentioned that he had been requested by ‘some principal civil and municipal guardians of the peace’, to dissuade the congregation and the wider Irish community from partaking in a hurling match in Sydney scheduled for 13 July.[11] This carries historical significance for a variety reasons and is a prime example of the Catholic Church enforcing its influence over the congregation, impacting their lives in relation to leisure and cultural expression.

The Very Reverend Archdeacon John McEncroe (1794-1868).[12]

Moreover, it showcases the complexity of the relationship that existed between the Catholic church, its patrons, civil society, and the governing authorities in the colonies. The influence of the church was evidently exploited where necessary by the authorities for civil or secular purposes. George Gipps, the Governor of New South Wales, and McEncroe were known to be in regular correspondence on several issues, mainly related to his displeasure at the administration of the commandants from Joseph Anderson to Alexander Maconochie.[13] The underlying politics at play ensured that McEncroe adhered to the request by colonial authorities’ to dissuade people from attending a hurling match on law and order grounds, a request he might have disregarded in different circumstances. He presumably had his own agenda; and more pressing concerns about the performance of the administration in New South Wales. He therefore duly obliged the authorities and told his countrymen that, as Christians, they were bound to keep the peace while ‘the innocent and manly game of Old Ireland’ could happen at some other time and occasion.[14] The request from the authorities was not altogether unreasonable, given that the date of the proposed hurling match was Monday 13 July 1846.

12 July is an Ulster Protestant celebration held since the eighteenth century to commemorate the victory of the Protestant king William of Orange over the Catholic king James II at the Battle of the Boyne (1690), which began the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. Today, large parades are held by the Orange Order and Ulster loyalists, not only in Northern Ireland, but throughout the commonwealth; the first Sydney Orange lodge was formed in April 1845 by Richard Muffin.[15] When 12 July falls on a Sunday, as it did in 1846, the parades are held on Monday 13; the Catholic population of Sydney and its surrounding areas was vehemently opposed to these commemorations in the long nineteenth century.

‘To Avoid even the very appearance of Evil’

– Rev. McEncroe appealing to his congregation not to partake in a scheduled hurling match, 1846.[16]

Undoubtedly, tensions rose between Catholics and Protestants at this time of year. Catholics would schedule hurling matches close to these dates to try an intimidate their Protestant counterparts from partaking in their demonstrations of their culture and identity. It was the belief of the Catholic Irish that by brandishing their hurling sticks, and showcasing the ferocity that which the games were played, they would intimidate Protestants, dissuading them from their commemorations.[17]

It could be claimed that McEncroe was not solely pushing his own political agenda but was interested in preserving the relative peace that existed in a religiously diverse area that possessed the constituents to revive old antagonisms and conflicts. Thus, he was only carrying out his duties as a clergyman in guiding his congregation in the right direction, away from violence in an effort to prolong the relative peace that existed in the multi-denominational area that was Sydney. According to the Morning Chronicle, the authorities were doing likewise by banning all expressions of cultural identity, assuring McEncroe that they would ‘take care and prevent any party procession or the public exhibition of any offensive banners’ on the date in question.

In conclusion, it is fair to assert that the relationship that existed between the Catholic church, leisure and culture in colonial Australian society did not conform to one specific bracket of classification. Religion, sport and politics were interwoven together and, as is demonstrated in press publications from the time, the circumstances surrounding the hurling matches described tell a much larger, more complex story. Hurling had the ability to congregate crowds in one area and, coupled with prevailing political and religious tensions, could have lasting ramifications, not just in one area, but for Protestant-Catholic relations throughout Australia. Furthermore, as is demonstrated here, the impact of a simple leisure activity such as a game of hurling, one that was played by the diaspora to preserve their heritage and identity, could influence political debates and decisions and leave a lasting impact across thousands of miles. This is still felt today not just in Ireland but all over the world where hurling is played.

REFERENCES:

[1] Patrick James O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, (Notre Dame, 1987), p.186

[2] Patrick Bracken, ‘The emergence of hurling in Australia 1877-1917’, Sport in Society, Vol. 19. No. 1, pp 62-73.

[3] See the depiction of a game of hurling 1906, National Library of Australia’s Trove, (https:/Trove.nla.gov.au/work/193133215?l-availability=y&q=hurling&c=picture&versionId=2114109830) (22 March 2017)

[4]‘Hurling’, Sportsman, 15 Oct. 1890, p. 7. National Library of Australia’s Trove, (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/227926470?searchTerm=hurling&searchLimits=l-state=Victoria|||l-title=1141) (22 March 2017)

[5] Bracken, ‘The emergence of hurling in Australia 1877-1917’, p.63.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., pp 62-73.

[8] Ibid.

[9]‘The rules of hurling’, Bendingo Advertiser, 7 Sep 1887, p.1. National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/88905464?searchTerm=the%20rules%20of%20hurling&searchLimits=)

[10] Bracken, ‘The emergence of hurling in Australia 1877-1917’ p.65.

[11]‘The hurling match’, Morning Chronicle, 8 Jul 1846, p.3, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31748398?searchTerm=hurling&searchLimits=l-availability=y|||l-decade=184) (22 March 2017)

[12] An image of Archdeacon John McEncroe. 1794-1868. National Library of Australia via AustLit (https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/A139511) (22 March 2017)

[13] P.K. Phillips, ‘John McEncroe’ in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (Melbourne, 1967) accessed online at Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mcencroe-john-2398/text3167) (24 April 2017)

[14] Ibid.

[15] O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, p.107.

[16]‘The hurling match’, Morning Chronicle, 8 July 1846, p.3, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31748398?searchTerm=hurling&searchLimits=l-availability=y|||l-decade=184) (22 March 2017)

[17] O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, p. 102.