Photo of Aboriginal Australian family Malka tribe, 1870 by Thomas J. Washbourne. Source: State Library Victoria

Stained by decades of oppression and mistreatment of indigenous peoples, along with frequent and widespread conflicts, the historical representation of the colonisers of the Australian continent from the earliest years of its colonisation in 1788 is rather unambiguously presented as a negative one – in both Aboriginal and European societies. Despite this, the lasting perception of the relationship between the Irish colonial settlers and Aboriginals is far more ambiguous. The Irish seem to have in many ways escaped the tag of ‘oppressive coloniser’ which has long been associated with their British colonial counterparts.

Perhaps owing to their shared experiences of oppression at the hands of British forces, or for their reputed more egalitarian nature, the Irish settlers have, at least in terms of their relationships with Aboriginal people, left behind a legacy as the ‘good colonisers’ of Australia.[1] Only in recent years has the role of the Irish people in the injustices against Aboriginals began to be recognised in a significant manner.[2] Through the examination of newspaper reports, private letters and with the aid of existing historiography, the following examines both individual and group interactions between Irish settlers and Aboriginals from 1800 to 1890 in order to assess the origins and the credibility of the long standing perception of the Irish as the ‘good colonisers’ of Aboriginal Australia, and proposes Irish settlers were no less prejudicial to Aboriginal people than were British or other European settlers.

A shared history of oppression

The study of the relationship specifically between Irish settlers and Aboriginals has received little scholarly attention. Two historians however, Ann Margaret McGrath and Patrick O’ Farrell have been incredibly influential in their evaluations of Irish and Aboriginal interactions throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, particularly around the term ‘Shamrock Aborigine’, a ‘sentimental nickname which denotes Aboriginal Australians with Irish descent’. This nickname points to an intimate relationship developed between the two groups. McGrath in particular has highlighted the positive and ever-growing intimate connection between the modern-day Irish and Aboriginal people and attempts to explain why many mixed-race Aboriginals seem far more willing to entertain Irish colonial ancestry than those with a heritage of other European or British countries.[3]

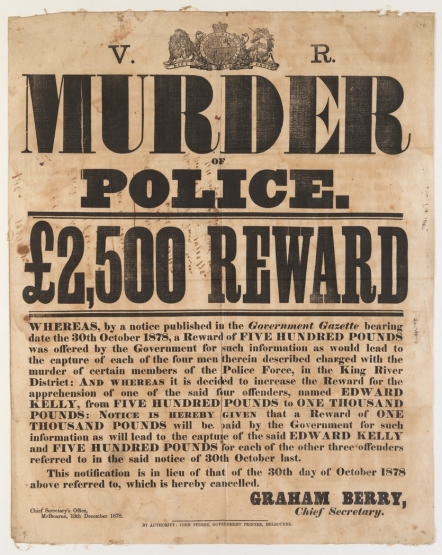

‘Wanted’ poster for the infamous Ned Kelly, 1878. Source: State Library New South Wales

One of the key elements contributing to the romanticised and idealised perception of the relationship between the Aboriginals and Irish may lie in the shared histories of dispossession of land and oppression at the hands of the British colonists. As McGrath has argued, many of the early Irish colonial settlers were themselves opponents of British rule in Ireland. Many had lost land and much of their freedom at home or had been forcibly transported to Australia as convicts. Stories such as that of Ned Kelly reveal tales of police harassment, unfair colonial administration, biases against the Irish and rebellions by these lower-class Irish against the ruling British class. These stories, which mirror the experiences of thousands of Aboriginals have been passed from generation to generation of both Irish and Aboriginal communities and have undoubtedly created connections between the Irish and Aboriginal people.[4] It is difficult to determine the extent to which these shared experiences of oppression and rebellion significantly impacted on the relationships and the perceptions Irish and Aboriginal people held of each other in colonial Australia. However, these experiences certainly helped create a lasting sense of solidarity between the two groups and an aboriginal Irish identity narrative which has been ‘forged out of centuries-long histories of British imperialism.’[5]

‘Assimilationist tendencies’

A further element which has enriched the positive perception of the Irish and Aboriginal relationship and one which is central to the work of Ann McGrath is the ‘assimilationist tendencies’ of the Irish and Aboriginal people.[6] Sexual relationships between native Aboriginal people and colonial settlers have taken place from the earliest years of foreign settlement on Australian shores and have been documented even within the most remote of Aboriginal towns.[7] The foundations of these sexual relationships, however, were often bound less by feelings of love, companionship and affection, but on economy and trade. Cameo Dalley has highlighted a number of cases of these commodified relationships between ‘blacks and whites’ where Aboriginal people ‘give the white man an Aboriginal woman.’[8] Hannah Robert has also noted the unstable and double-edged nature of sexual relationships between colonisers and natives: on the one hand, she contends that these relationships demonstrated the violation, racism and sexism which have long characterised colonial native relations; on the other hand, they may have demonstrate the possibility of personal interaction, negotiation and partnership between colonisers and colonised.[9]

In 1879 the New England Advertiser newspaper included an article which highlighted the effects these relationships had on the Aboriginal people, stating that the ‘black women and their half cast’ children lived in the most destitute of conditions and were outcast by their Aboriginal tribes and neglected by their white male partners/ fathers.[10] The lack of support provided by ‘white males’ for their partners certainly demonstrates a sexually exploitative and often violent relationship between the Aboriginal people and ‘white’ settlers. Alternatively, in terms of the Irish colonial history of sexual relations with Aboriginals, Patrick O’ Farrell falls heavily on the latter of Robert’s two propositions. He suggests that, in contrast to ‘protestant or paternalist whites’, Irish Catholics treated Aboriginal people ‘as human beings, as equals’ and suggests this equality often extended to marriage, in a manner which was distinctly different from the sexual exploitation common amongst other ‘white’ relations with Aboriginals.[11]

The primary piece of evidence O’Farrell offers to support his claims of Irish egalitarianism lies in what he perceives as the common existence of ‘Shamrock Aboriginal’ surnames. Contemporary nineteenth-century sources however do not support O’Farrell’s assertions. Newspaper reports that mention Aboriginal people show considerable lack of evidence for the existence of ‘shamrock Aboriginal’ surnames; rather, many are identified by their tribe name or simply as ‘natives’.[12] McGrath has also outlined some of the inadequacies of O’Farrell’s claims, arguing that the existing ‘shamrock Aboriginal surnames’ do not serve as definitive proof of strong intimate relationships between the two groups. She contends that in accordance with colonial and state administrations, a ‘surname’ was required by authorities in order for a person to receive blanket handouts, to be accounted for in census records and for use in other official documentation. Aboriginal people often did not speak English, nor did they make use of patrilineal ‘surnames’. Because of this, police or those who gathered information from the Aboriginal people, many of whom were Irish, often allocated their own surnames to local Aboriginal people for official purposes.[13] Certainly many ‘Shamrock Aboriginal’ surnames may have originated from the offspring of intimate relationships between Irish settlers and Aboriginal people, but as McGrath has noted, it is important to approach O’Farrell’s assertions with caution.

Irish participation in Aboriginal atrocities

Thus far the primary arguments behind the perception of the Irish as the ‘good colonisers’ of Australia have been assessed and both their strengths and weaknesses have been highlighted. Yet compelling evidence also exists which suggests the Irish colonisers were in no significant way more likely to approach Aboriginals in an egalitarian manner than were British or European colonists. Moreover numerous cases of Irish settlers serving as catalysts in great atrocities against Aboriginal people have also been documented.

On 10 March 1879 the Geelong Advertiser published an article titled ‘Massacre of Blacks’ which reported on an incident in which twenty-eight Aboriginal men of the Guugu-Yimidhirr tribe were shot and drowned at Cape Bedford in the Cook District of Far North Queensland. Headed by Irish born sub-inspector Stanhope O’Connor, six troopers tracked down the Aboriginal men, ‘hemmed the blacks within a narrow gorge’ and eventually shot twenty-four of the men, allowing the remaining four to swim out to sea, where they inevitably drowned.[14] This barbaric ‘hunting’ of Aboriginal people by Irish colonisers was not an isolated incident. The Wathaurong weapons, which are currently held at the National Museums Northern Ireland pay testament to the Irish involvement in frontier in colonial Australia. The collection of weapons, which includes shields, clubs and boomerangs were constructed by the Aboriginal Wathaurong people of Victoria in the 1830s and taken by Irish brothers John and Robert William Von Stieglitz. The brothers were descendants of a baron of the Holy Roman Empire who had emigrated from Bavaria to Ireland in the early 1800s. The family had been poorly provided for and decided to emigrate to Van Diemen’s Land, arriving at Hobart in 1829. Two brothers got land there but John and Robert William did not so were amongst the earliest Europeans to settle at Port Philip near Melbourne.[15] Like Stanhope O’Connor, they admitted to ‘hunting’ Aboriginal people that had supposedly caused harm to white settlers and animals.[16]

Shield made by Wathaurong people, Victoria c.1836,

National Museums Northern Ireland. Source: National Museum Australia

An article in the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate in 1883 provides a further example of Irish cruelty of Aboriginal people. It highlighted an incident in which an Irish man fired upon a crowd of Aboriginals which he claimed were killing his sheep in Western Australia. Alexander Crawford, an Ulster native who moved to the Aboriginal lands of Murchison, reportedly came under attack from the local people and was ‘speared in the arm’ before retaliating with his gun.[17] It is clear that this newspaper leaned toward the innocence of Alexander Crawford, painting him as a victim and describing the Aboriginals as ‘savages’. O’Farrell’s The Irish in Australia, however, contains extracts of letters between Crawford and members of his family (living back in Ireland), in which it is apparent that Crawford was far from egalitarian in nature and was involved in many violent and deadly altercations with the Aboriginal people. The letters indicate Crawford’s family were appalled by his actions and appealed to him to change his treatment towards the native people. In one extract, his father wrote: ‘I hope you are getting on with the natives better … kindness goes far with them. Probably if you tried some of this you might do better.’[18] Letters from a Lillie Mathews also suggest disgust towards the actions of Crawford: ‘Oh my darling keep your hands free from your fellow creature’s blood. For you to need to fire on them makes me feel miserable’.[19]

From the exploits of Stanhope O’Connor to those of the Von Stieglitz brothers, to the latter mentioned experiences of Alexander Crawford, these occurrences provide an alternative perspective of the Irish and Aboriginal colonial experience. By acknowledging the calamities that the Aboriginal people experienced at the hands of the Irish settlers, the image of Ireland as the ‘good colonisers’ of Australia becomes more fractured and controversial. However, in the same way that the shared histories of colonial oppression or the existence of ‘shamrock Aboriginal’ surnames do not exemplify the historical Irish-Aboriginal relationship as a positive one; the above-mentioned calamitous events certainly do not epitomise all Irish coloniser and Aboriginal relationships as negative. As with any interaction between great masses of people, the relationship between the Irish settlers and native peoples of the Australian continent is not simply ‘black and white’. Rather, it is a complex and multifaceted one that should be approached in a balanced and impartial manner.

REFERENCES

[1] Anne McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines: the Irish, the Aboriginal Australians and their children’, Aboriginal History, 34 (2013), pp 55-84: 56.

[2] Simon Carswell, ‘Irish played part in atrocities against Aboriginal people – Australian MP’, Irish Times, 2017 (https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/irish-played-part-in-atrocities-against-aboriginal-people-australian-mp-1.3259993).

[3] McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines’, pp 55-56.

[4] Sharon M. Crozier-De Rosa, ‘’Not Just Ned: A true history of the Irish in Australia’. Safeguarding against ‘a shallower and a poorer play’, Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, 1 (2011), pp 1-9: 1.

[5] McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines’, p. 56.

[6] McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines’, p. 58.

[7] Cameo Dalley, ‘Love and the stranger: Intimate relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in a very remote Aboriginal town, northern Australia’, The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 1 (2015), pp 38-54: 40.

[8] Dalley, ‘Love and the stranger’, p. 43.

[9] Hannah Robert, ‘Disciplining the female Aboriginal body: interracial Sex and the pretence of separation’, Australian Feminist Studies, 34 (2001), pp 69-81: 70.

[10] ‘The condition of the Aboriginals’, New England Advertiser, 14 June 1879, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/62086388)

[11] Patrick O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia (1st ed., Kensington, 1987), p. 72.

[12] ‘Aboriginal murderers’, Geelong Advertiser, 31 August 1861, National Library of Australia’s Trove. (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/150307701)

[13] McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines’, p. 59.

[14] ‘Massacre of Blacks’, Geelong Advertiser, 10 March 1879, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/150420896)

[15] K. R. Von Stieglitz, ‘Von Stieglitz, Frederick Lewis (1803–1866)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2 (1967), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/von-stieglitz-frederick-lewis-2761/text3915) (12 May 2018).

[16] Crozier-De Rosa, ‘Not Just Ned: A true history of the Irish in Australia’, p. 5.

[17] ‘Western Australia’, Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 12 July 1883, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/135954651)

[18] James Wright Crawford, accessed via McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines’, p.61.

[19] Elizabeth Jane (Lillie) Mathews, accessed via McGrath, ‘Shamrock Aborigines’, p.61.