In much of Australia, the Irish had varying levels of success, making a life for themselves in the land down under. Many arrived as convicts, or convicts’ relatives in the first colonies. Willey states that up to a third of the convicts were Irish. For the most part, general historiographical consensus as confirmed by Eric Richards is that the Irish in Australia were able to be successful and mark their place in Australian history. South Australia was not a penal colony but a planned colony which affected the Irish emigrant experience and whether they were able to meet their various goals of success in that colony. The Irish experience in Australia already was very diverse, depending on what circumstances the Irish were emigrating from, their social status, amount of capital, whether they were free or convicts.

The South Australia colony, particularly Adelaide, added to this diverse experience. Many of the Irish, particularly freed convicts, assisted in Australia’s founding by populating and assisting with legal matters, and did quite well for themselves. Eric Richards notes that while it was possible for the Irish to do well in Adelaide, it was not as easy for them to achieve their dreams of success as in other colonies. The Irish were subject to discrimination and marginalisation as a minority, they had a lack of education and training, and their various socioeconomic backgrounds contributed to their journeys to finding success. Though the Irish generally did well financially and socially in Australia, they did not have as much opportunity to prosper in Adelaide, South Australia as in other colonies because of their discrimination/marginalisation, their education or lack thereof, and their socioeconomic backgrounds. While South Australia may not have been necessarily anti-Irish, there were multiple other factors causing the Irish to have a more difficult time in Adelaide.

The Irish as a minority

South Australia tells a slightly different story with the fewest proportion of Irish immigrants. Eric Richards notes that South Australia, specifically Port Adelaide received less Irish immigrants than other regions of Australia. Perhaps this was because South Australia was a new colony, and less established than the others, but there are other factors as well. Adelaide’s Irish population came mostly in the late 1840s and later, slowly becoming one tenth, but never one third of the population. In the first five years after Adelaide’s establishment, the Irish made up less than seven percent of the population.[1] Isabella Wyly, one of the Protestant girls that arrived through subsidy in the early 1950s wrote of multiple marriage proposals from Englishmen, and her eventual husband was the first (and presumably only) Irishman to propose to her.[2]

As well, South Australia originally restricted the immigration of Irish Catholics.[3] The colony actually advertised itself to Protestants as a ‘haven for protestant dissenters’, and its founders ‘set their faces against the creation of a Catholic population.’[4] Fitzgerald writes of it being called a ‘paradise of dissent.’[5] The advertisement of itself as a predominantly Protestant colony would have been a strong dissuasion for Irish Catholics moving to South Australia. The founders’ desire to have a Protestant colony created a keen disadvantage for Irish Catholics from the earliest beginnings as they could be turned away or potentially treated unequally to their Protestant counterparts. Because many (though not all as exemplified by the Wyly family) Irish were Catholic, the Irish were not migrating to Adelaide from it’s establishment, but from much later, giving them an additional disadvantage, as they were not established in the community in any way, and likely had few points of chain migration in Adelaide. Fitzgerald notes that Isabella Wyly wrote in her letters that she arrived in Adelaide knowing no one, and that she had a deep sense of loneliness and isolation, but also that some of her extended family arrived in Adelaide soon after.[6] The Irish were not only a minority in population in Adelaide, but also in religion.

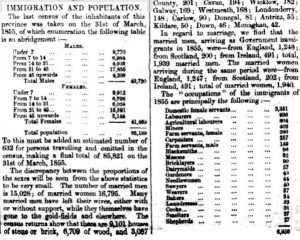

After 1836, the Irish population rose, varying from ten to forty percent.[7] In the 1850s there was a rise in Irish immigrants, as the restrictions on Catholic admission had been raised, and single ladies were needed as wives and workers. As seen in the 1955 census published in the Adelaide Observer and the South Australian Register, the Land Fund brought 4,049 single women to Adelaide in 1855, 2,981 of whom were Irish, and 2,540 were Catholic.[8] Of the 311 bounty girls in the depot recorded in the census, only 158 had actually applied to travel to Adelaide. Over half of the girls had applied to land elsewhere in Australia, and this could be an indicative of Adelaide’s views on the Irish, and vice versa. The other colonies may have been more attractive to the Irish because they were more tolerant of Catholics, and there would have been more Irish to interact with assisting them with the transition to Australia. Because the Irish were more prominent in the other colonies, it is also possible that the immigrants were chain migrating, finding homes with relatives or friends in the same colony, rather than a new one with no familiar faces. The Irish were originally marginalised, and were realistically a minority in Adelaide, South Australia. Their experience through this would have made it more difficult to find success in South Australia.

Level of Education and Training

Another reason the Irish had a more difficult time finding success in Adelaide was because of their education and training, or lack thereof. The 1855 census listed in the South Australian Register, and the Adelaide Observer recorded the immigrants’ jobs, and many of the men were listed as farmers or agricultural labourers. Of the single women that emigrated, 3,481 were listed as domestic servants in the census.[9] The articles note that the problem of these records were that the ladies were recorded as belonging to the designation where she wanted to obtain employment, rather than where they were actually qualified to work. Many, if not most of these girls were from low income families and would not have known how to go about being a domestic servant for an upperclassman household, not having been raised with the knowledge of upper class etiquette and lifestyle. In fact, the news articles write that most of the domestic servants should have actually been listed as farm servants. The girls did not want to work as farm servants, rather they wanted domestic work which they were unqualified for giving them limited work opportunities.

Isabella Wyly is a good example of one of these girls. She arrived in Adelaide orphaned, and penniless, though from a middleclass background.[10] Finding jobs in Adelaide was hard to begin with, but eventually Isabella was employed by the Baggets in drapery, a job which she knew nothing about.[11] To her credit, Isabella learned quickly and was able to create a career for herself in drapery, but others did not have her luck. The people from Ireland arrived in Adelaide, expectant to do well and thrive, but were inhibited in reaching their goals because they were unqualified for the jobs they wanted.

Not only were they unqualified, but they were also uneducated. Few said they had an education, and those who did usually came from a Protestant background as Isabella was. As seen in the census, most of the girls that immigrated to Adelaide were Catholic, not Protestant (2,540 Catholic, 1,500 Protestant).[12] Being Catholic may have been a disadvantage because of their late acceptance into the colony, but the Catholic girls may have been disadvantaged further through their lack of education. Of the 14 to 21-year-old girls arriving because of the Land Fund, 569 could read, all that could read could write, and 397 could not do either. Those aged 21 and older: 675 could read, 928 could write, and 966 were listed as incompetent.[13] With these figures, 1,244 could read, 1,497 could write, and 1,363 were illiterate. This makes likely less than half of the population of single ladies having some form of education. Their religion affected their access to education, and so with 2,540 Catholic girls, and 1,263 girls having been illiterate, a fair chunk of the Catholic girls may have been grossly uneducated.

Isabella Wyly had some education, being able to read and write, though her letters had many spelling and grammatical errors. She was from a middle-class Protestant family, and part of the younger age groups which statistically had better education levels, but she seems to have had only a modest education. With little to no education, there would be few opportunities for them to further their skills to procure better jobs. As it stands, the single Catholic Irish ladies in particular, were not set up for success in Adelaide because of their lack of education and training.

Socio-economic Backgrounds

Another way the Irish in Adelaide had a more difficult time finding success was because of their socioeconomic backgrounds. When Wakefield was proposing the colony, one of his reasons for the colony was that the Irish could be transported to Australia, rather than England in their search for work.[14] Torrens claimed that the reason for mass poverty in Ireland was because the amount of labourers exceeded the amount of land that needed to be worked.[15] The Irish were immigrating to Australia because they were searching for more work opportunities. If they were already poor or destitute in Ireland, they would not have been able to pay for their own passage, much less bring any capital with them. Richards writes that the Irish ‘on average may have been poorer and more rural than the majority of immigrants.’[16] The Irish were looking for better opportunities and there was a need in Australia for rural labourers. According to Richards, about half of the Irish, including Isabella Wyly, needed some government assistance and the other half needed full subsidisation for their passage.[17]

The single women that arrived in Adelaide (5,000 total) hailed from destitute (or nearly destitute) families. Not only were they disadvantaged because they were women, likely Catholic, and uneducated causing fewer job opportunities, they were also incredibly poor to begin with. There would have been little room for educating themselves to obtain better jobs, or for sending money back home to take care of their families. Isabella Wyly, though Protestant, is a classic example of this. She arrived with no money, her only experience was being a servant in Dublin, and she arrived with great expectations.[18] It was not until she had established herself in Adelaide that she was able to start sending money back home as she mentions in her letters. Once she was established, Fitzgerald shows her confidence that she was doing better financially and socially than she possibly could have in Dublin.[19] Isabella was able to become greatly successful in Adelaide, but her story is not every Adelaide Irishman’s.

There were also nomination schemes in place, where someone in Australia could nominate a friend or family member to be brought to Australia. Richards shows that those who were nominated usually fared better than those who were not. This makes sense because the Irish person arriving in Australia would have family or friends that were already there providing them some financial and cultural support. When immigrating, it is much easier to immigrate through chain migration, knowing there will be a support system there rather than arriving in a new place with nothing and no one, trying to do better for yourself. With no money, it was hard for the Irish to emigrate without assistance. Chain and family migration also accounts for the larger numbers of Irish migrating to Sydney and Melbourne as immigrants would usually settle near their family or friends. If an Irish person arrived, they would usually be supported by their nominator, and as there were fewer Irish in Adelaide, there would be less chain migration. The Irish did not have excess wealth to spend on fares to Australia: they came dirt poor, needing help to settle in. Without money or land, they had a lower social status, thereby increasing their difficulty in gaining success in Adelaide than in other colonies.

The Irish had a more difficult time doing well in Adelaide than in Melbourne or Sydney. The Irish were technically a minority in Australia as a whole, but did make up a large portion of the early Australian population. In Adelaide, they were much more of a minority, causing them to be at a disadvantage to their British neighbours. The majority of the Irish in Adelaide were Catholic, in an effective Protestant colony adding to their minority level. The Irish were also highly uneducated and unqualified for the jobs they were hoping to obtain. Already a minority, their chances of finding suitable work becomes even smaller. Irish immigrants to Adelaide were usually hailing from rural Ireland, and were severely disadvantaged and poor. Coming to Australia through government assistance, they had no means to pay for an education, or training to find their desired work. While the Irish in Australia did well, marking their place in Australian history, the Irish in Adelaide did not have the means, education, or social advantage that the English did, causing them to have less of a lasting impact on Adelaide. Australia gave the Irish very diverse experiences in their settlement. While their social status, financial status, and education influenced their experience, their location within Australia did as well.

REFERENCES:

[1] Eric Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’ in Irish Historical Studies, 27 (1991), p. 216; 219.

[2] David Fitzpatrick, ‘‘These golden shores’: Isabella Wyly, 1856-77’ in Oceans of consolation: personal accounts of Irish migration to Australia, (Ithaca, N.Y., 1994), p. 101.

[3] Keith Willey, ‘Australia’s population’ in Labour History, 35 (1978), p. 3.

[4] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress South Australia’ pp 217-219.

[5] Fitzpatrick, ‘‘These golden shores’: Isabella Wyly, 1856-77’, p. 100.

[6] Fitzpatrick, ‘‘These golden shores’: Isabella Wyly, 1856-77’ pp 97-98.

[7] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress South Australia’, p. 220.

[8] South Australian Register, 1 Jan. 1857 National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/49763012?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FS%2Ftitle%2F41%2F1857%2F01%2F01%2Fpage%2F4146436%2Farticle%2F49763012) (26 Apr. 2017); Adelaide Observer, 10 Jan. 1857 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/158115607/18795019) (26 Apr. 2017).

[9] Ibid.

[10]Fitzpatrick, ‘‘These golden shores’, p. 96.

[11] Isabella Wyly, ‘The Wyly letters, 1856-77 (1-10)’ in David Fitzpatrick (ed.), Oceans of consolation: personal accounts of Irish migration to Australia, (Ithaca, N.Y., 1994), p. 114.

[12] South Australian Register, 1 Jan. 1857 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/49763012?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FS%2Ftitle%2F41%2F1857%2F01%2F01%2Fpage%2F4146436%2Farticle%2F49763012) (accessed Apr. 26, 2017).

Adelaide Observer, 10 Jan. 1857 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/158115607/18795019) (accessed Apr. 26, 2017).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress South Australia’ p. 217.

[15] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress South Australia’ p. 217.

[16] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress South Australia’ p.220.

[17] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress South Australia’ p. 222.

[18] Fitzpatrick, ‘‘These golden shores’’, p 97.

[19] Fitzpatrick, ‘‘These golden shores’’, p. 99.