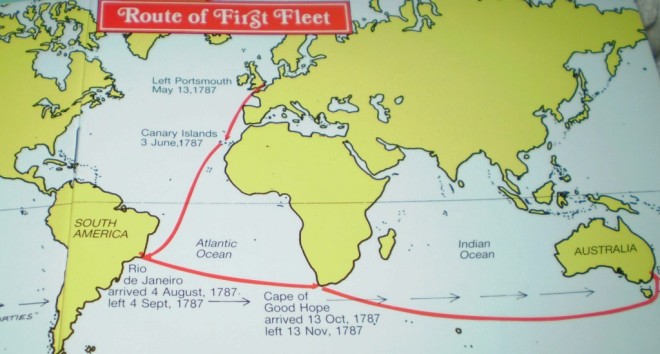

Route of the First Fleet, 1787. Source: First Fleet Fellowship Victoria

Eimear McCarthy ~ Kate O’Gorman ~ Paul Clifford ~ Shauna Higgins

On 13 May 1787, by order of George III, a fleet of eleven ships under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip set sail from England for the landmass known today as Australia. This First Fleet consisted of between 1,000 and 1,500 people, including marines, government officials, and their families along with 548 males and 188 female convicts. The aim was to found a penal settlement but this would soon become the first European colony on the continent. Phillip, in his flagship Sirius, entered Port Jackson (Sydney) on 26 January 1788.[1]

As a response to a lack of space to imprison convicts, the British government had decided that it was cheaper and easier to transport them overseas, away from the general population. Theft of livestock, pigs and cattle, was by far the most common offense in Ireland which resulted in transportation. Between 1791 and 1853, approximately 26,500 Irish people were convicted of trivial crimes and transported to New South Wales. It is estimated that Irish people counted for around one-third of the population of early colonial Australia and are therefore vital for exploring all areas of the convict experience. It will be argued here through the utilisation of both primary and secondary sources that many Irish convicts were mistreated during their voyage to and after arriving in colonial Australia.[2]

Mistreatment of Irish convicts can clearly be seen through the case study of the Phoebe Dunbar convict ship which ported in Western Australia in 1853. (While this was the last ship to arrive from Ireland, it was not in fact the last ship to transport Irish convicts. In 1868, for example, sixty-three Irish Fenians were convicted in Ireland but incarcerated in England and transported to Australia on the Hugoumont, the last ship to sail from England with convicts as late as 1868.[3]) The Phoebe Dunbar had a higher rate of mortality due to mistreatment than other convict ships of this late period in Australia’s transportation history; the ship’s medical journals and newspaper articles of the time provide some contemporary insights.

Female Irish convicts experienced ill-treatment in many forms in colonial Australia. Women were a minority in the patriarchal society of the penal colonies and women convicts were discriminated against in convict society not only on gender grounds but also because of their ‘Irishness’. They sometimes resorted to prostitution and many were put into factories, another form of harsh imprisonment which was meted out to convict women. These women’s experiences are important as many of the source materials available – and consequently historical narratives – have tended to misrepresent these women or focus on the male experience.

Religion is another factor which contributed to and facilitated the mistreatment of Irish convicts. A large proportion of Irish convicts identified as Catholics in a colonial environment where the colonisers were Protestant. This caused difficulties and facilitated discriminatory practices against them. Therefore it is necessary to consider the role that religion played in defining and shaping the Irish convict experience as a form of identity and its significance in a convict environment.

Political conflict in incidents such as the Castle Hill rebellion in 1804 formulated an identity and historical perception of the Irish Catholics in Australia as rebellious; a nationalist and anti-authoritarian nature is synonymous with the popular image of the Irish convict. In considering this element of the Irish convict’s nature it is possible to assess misrepresentation but also the extent to which many of the Irish convicts were actually rebellious in nature and the ways this occurred due to ill-treatment from colonial authorities.

REFERENCES

[1] ‘The Voyage’, First Fleet Fellowship Victoria (https://firstfleetfellowship.org.au/ships/the-voyage/) (26 April 2017); Robert Hughes, The fatal shore (New York, 1988) p.2

[2] See Patrick O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia: 1798 to the present day (Cork, 2001).

[3] Robert Hughes, The fatal shore (New York, 1988) p.152; 578.