World War One pro-conscription propaganda, 1916. Source: Migration Heritage Centre

Australia’s main expeditionary force during the First World War was the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), a well-trained, highly effective but voluntary military outfit. As the war dragged on, enlistment levels across the Western forces dropped significantly and by the middle of 1916, those for the AIF had fallen to their lowest levels yet. Although the government of the newly federated country had the power to conscript, Prime Minister W.M. (Billy) Hughes wanted to obtain popular support – legitimation both for Australia’s contribution to the war and his leadership of the government. Following two failed conscription referendums, Roman Catholics were blamed as their vociferous opposition made them easy to be perceived as disloyal. Citizens were asked in October 1916: ‘Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?’

The second referendum held in December 1917 softened some of the conditions and modified the question to ‘Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the Australian Imperial Force overseas?’ – but had the same result for which Catholics were blamed. The evidence shows that the Roman Catholic Church in Australia was threatened by the federal government as, under the proposed terms of conscription, religious figures would not be exempt. For this, and other, reasons most Catholics strongly opposed the introduction of conscription in 1917. Animosity towards Catholics, the majority of which were Irish, was expressed through the circulation of anti-Catholic materials such as pamphlets and posters, propaganda that ultimately created a sense of excluding the Irish Catholics from British-Australian national identity. In terms of the historiography of the period it is agreed by most historians, among them Jeff Kildea and Martin Crotty, that the Catholic Church and the media of the time played incredibly significant roles in the anti-conscription campaign.

Newspapers in particular were effective in spreading anti-conscription and anti-Hughes propaganda throughout this campaign. Titles such as The Methodist were also useful in gaining an insight into the kind of anti-Catholic propaganda that had been circulated during this period. For this reason, both anti-conscription and anti-Catholic newspapers are used as primary sources here as they gave an insight into public opinion of the time. It will be argued that Prime Minister Hughes himself played a significant role in the failure of the 1917 conscription referendum, as a result of his antagonism towards and attempted isolation of the Irish Catholics.

Conflating Catholicism and Irishness

Prejudices against the Irish emerged soon after the rejection of the 1916 referendum as both the printed media and Hughes blamed its failure on the Catholics.[1] With the approach of another conscription referendum in 1917 tensions mounted once more between the Irish Catholics and those who considered themselves to be loyal to the British Empire. Within communities, families who had not sent their sons to fight in the war were publicly shamed, as men who remained on the Home Front were labelled ‘shirkers’ and cowards.[2] Due to the failure of the 1916 referendum, a divide emerged as people began to view Australian Catholics as Irish. Despite having been born in Australia, the Catholics of an Irish background struggled with their national identity, partly because of how events in Ireland were playing out since the 1916 Easter Rising.

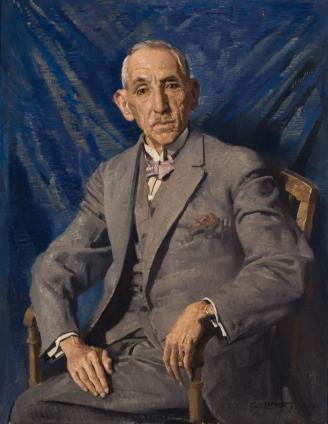

Painting of Prime Minister William Morris Hughes by George Washington Lambert, 1927. Source: George Lambert Exhibition

Public opinion of Irish Catholics was generally one of suspicion and mistrust. This was prevalent throughout the media as newspapers such as The Methodist declared, ‘that Romanism is anti-British and disloyal, and that the Vatican is in league with Germany’.[3] Propaganda such as this was not uncommon in Britain, not least because of the links between Irish Republicans and Germany, and in the lead-up to the 1917 referendum in Australia, anti-Catholic pamphlets were widely produced. Catholics were naturally outraged by the circulation of these pamphlets, yet when they looked to Hughes to put a stop to this form of propaganda, he refused. Hughes was severely criticised by both the Catholic hierarchy and sympathetic newspapers for the failure of his government to ban the material.[4] As Kildea has stated, Catholics turned their backs on the government and blamed Hughes as ‘the Prime Minister was responsible, inasmuch as he had the power to put a stop to the vile insults offered to Catholic citizens’.[5] With this in mind, it is little wonder that Catholics felt little loyalty towards the state.

The highly influential Irish-born Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, played a significant role during this period as his anti-conscription utterances and biting wit aimed at Hughes appealed to the Irish Catholics.[6] Throughout his campaign, Mannix reminded the Irish Catholics of Britain’s many betrayals of Ireland and argued that the duty of Australians was not to that Empire but to the Commonwealth of Australia, thus encouraging Catholics of Irish birth or ancestry to once more view themselves as Australian.[7] In playing to the sense of Catholic marginalization in Australian society, Mannix became increasingly popular among anti-conscriptionists.[8]

The anti-conscription campaign gained further influence with the active involvement of the Catholic Church hierarchy. During the 1916 referendum the Church had maintained the position that the referendum was a political issue for individuals to decide.[9] In line with this position, the Apostolic Delegate issued a letter stating: ‘It would be altogether unreasonable to involve the Church … in an issue which its members, as citizens in common with others, are call on to decide’.[10]

‘It would not please God’

However, the attitude of the Church soon changed with the prospect of seminarians and teaching brothers being conscripted in 1917.[11] The upcoming referendum further threatened the Church as teaching brothers in the Catholic schools could be conscripted resulting in these schools being closed down. Due to this threat, the Catholic hierarchy became increasingly active in the campaign using the Sydney-based Catholic Press to encourage their parishioners to vote ‘No’ in the upcoming referendum: ‘It would not please God. It would be an outrage upon God’.[12] Further to this, Pope Benedict XV issued a ‘peace note’ calling for all nations to abolish compulsory military training. For Protestants, this note confirmed long held ideas about Catholic loyalty to their Church superseding their loyalty to any state; in this case, they believed that Catholics worldwide were uniting to undermine the British Empire.[13] The Methodist newspaper was explicit in its response to the peace note: ‘Romanism at heart is disloyal and desires the downfall and dismemberment of the Empire as a great Protestant power.’[14]

As well as the Catholic Church, the printed press played a significant role in the anti-conscription campaign. Newspapers like the Catholic Press attempted to influence Catholic voters on the day of the 1917 referendum by publishing speeches made by various bishops. Striking statements included: ‘Those who vote “Yes” imperil the liberty and lives of all the teaching Brotherhoods and clerical students’ and ‘If they are conscripted all our boys’ schools all the ecclesiastical colleges in the Commonwealth will be closed’.[15] Newspapers like the Southern Cross in Adelaide, South Australia, were effective in encouraging Irish Catholics to oppose conscription and the government:

‘It should be well known far and wide that Mr. Hughes definitely refused to sanction the exemption from military service of religious lay brothers and Christian and Marist Brothers, and other teachers in our largest boys’ schools’.[16]

Hughes recognised the influence that newspapers such as these had and approached the editor of the Catholic Press, Tighe Ryan, in an effort to gain Catholic support. He made an offer to Ryan that if the newspaper ceased its printing of anti-conscription material, he would use his political influence to have the Home Rule Act put into motion in Ireland at once. Although this offer was declined, Hughes went on to claim that he had convinced the British government to abolish martial law in Ireland. In response to this, Ryan published a House of Commons ministerial statement proving that this claim was indeed false.[17] Due to Hughes’ actions, Irish Catholic mistrust in the Hughes government only increased.

Syndicalists, Sinn Féin and Shirkers

Suspicion of the Hughes government was not unwarranted, as the Prime Minister was quite blatantly anti-Catholic. He ultimately blamed the failure of the 1916 conscription referendum on the Church, despite the Church having taken no public stance on the matter.[18] During the 1917 conscription campaign, it could be said that Hughes made little effort to gain the support of the Irish Catholics, despite believing that their vote would be significant in the upcoming referendum. In 1936, a Sydney tabloid, Smith’s Weekly, exposed a ‘sensational piece of history’ by publishing a facsimile copy of a ‘secret and personal’ cable message from Hughes to General Birdwood at AIF Headquarters in France twenty years previously. In it, Hughes told the Birdwood on 14 October that it was ‘absolutely imperative in imperial interests as well as Australian interests that the [first] referendum should be carried by a large majority.’ He attributed ‘very strong’ opposition to it to

‘wilful misrepresentation disseminated by certain sections which include Syndicalists, Sinn Féin and Shirkers … The overwhelming majority of the Irish votes in Australia which represent nearly 25 per cent of the total votes has been swung over by the Sinn Féiners and are going to vote No in order to strike a severe blow at Great Britain’.[19]

In an attempt to gain the support of the Catholics after the failed 1916 referendum, Hughes promised to introduce a bill which would exempt brothers and clerical students from conscription. However, Irish Catholics refused to believe this statement, showing the level of mistrust felt by the Catholics for Hughes and his government. The Bishop of Lismore in Sydney, John Carroll noted: ‘That was only a personal promise and did not carry the official promise of the Government’.[20] Further to this, the evidence would suggest that feelings of contempt were mutual as Hughes felt that the Catholics were carrying out a personal attack on him. In 1916, the Prime Minister told London-based journalist Keith Murdock: ‘the bulk of the Irish people … are attacking me with a venomous personal campaign.’[21]

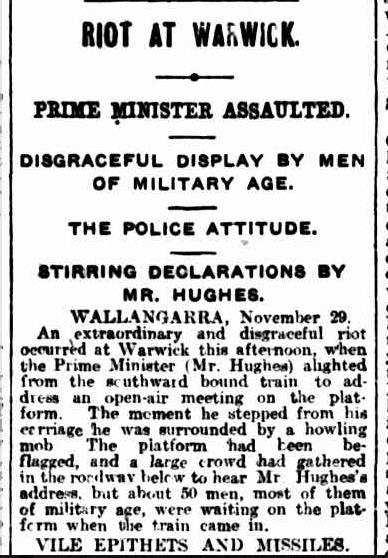

Riot following the egging of Prime Minister Hughes, 1917. Source: The Brisbane Courier

Hughes’ unpopularity among the Irish Australian Catholics grew more and more evident; on one occasion in Queensland, the Prime Minister was egged by an Irish Australian. When Hughes insisted that the egg-thrower be arrested, the policeman present, who was also Irish Australian, refused to do so. From this, Hughes’ unpopularity among Irish Catholics became apparent. His refusal to exempt religious figures from conscription, as well as allowing anti-Catholic pamphlets to be distributed, resulted in significant losses of Catholic support. However, it should be noted that Hughes was in fact in support of Home Rule in Ireland and had actually made representations to the British government to end martial law and implement Home Rule.[22] It could be argued that if the Irish Catholics had been aware of Hughes’ efforts, it is likely that he would have gained more support from Irish Catholics. However, Hughes ultimately wished to maintain his image as the abrasive anti-Sinn Féiner who was constantly harassed by disloyal Irish Catholics. This was an image in which Hughes intended to promote as it was in line with Protestant establishment opinion at the time.[23]

It is clear that as a result of the actions of Hughes, most Irish Catholics felt little or no loyalty towards the Australian government during the First World War. Due to the wide circulation of anti-Catholic sentiment as well as the lack of support from the Hughes government, Catholics felt isolated from Australian society. However, with the involvement of Archbishop Mannix in the anti-conscription campaign, Irish Catholics were encouraged to consider Australia first, rather than the British Empire, thus encouraging Irish Catholics to consider themselves a vital cog in the Australian nation. Furthermore, with the engagement of the Catholic hierarchy in the campaign, they were spurred to protect the Church from conscription. The role of the press during this period cannot be overlooked as their coverage and commentary on the anti-conscription campaign proved to be incredibly significant. In spreading anti-conscription propaganda, as well as exposing the deceitful tactics of the Hughes government, newspapers such as the Catholic Press could certainly be credited in the preventing of conscription. It could be argued that Hughes himself aided in the failure of the 1917 referendum, as in his isolation of the Irish Catholics, the anti-conscription campaign became all the more influential.

REFERENCES

[1] Martin Crotty, ‘Social conflict and control, protest and repression (Australia) in 1914-1918 – online. International encyclopaedia of the First World War (2008), p. 8 doi:10.15463/ie1418.10605 (8 April 2018)

[2] Joan Beaumont, ‘Conscription (Australia)’ in 1914-1918 – online. International encyclopaedia of the First World War (2016), p. 5, doi:10.15463/ie1418.10554. (8 April 2018)

[3] The Methodist, 24 Nov. 1917.

[4] Jeff Kildea, ‘Australian Catholics and conscription in the Great War’ in Journal of religious history, 26 (2002), p. 302.

[5] Jeff Kildea, ‘Paranoia and prejudice: Billy Hughes and the Irish question 1916-1922’ in Echoes of Irish Australia: rebellion to republic (2002), p. 160. Kildea’s article title inspired this section’s title.

[6] Kildea, ‘Conscription in the Great War’, p. 304.

[7] Kildea, ‘Paranoia and prejudice’, p. 160.

[8] Beaumont, ‘Conscription (Australia)’, p. 6.

[9] Kildea, ‘Conscription in the Great War’, p. 298.

[10] The Catholic Press, 5 Oct. 1916.

[11] Kildea, ‘Conscription in the Great War’, pp 298-299.

[12] The Catholic Press, 29 Nov. 1917.

[13] Kildea, ‘Conscription in the Great War’, p. 303.

[14] The Methodist, 8 Dec. 1917.

[15] The Catholic Press, 20 Dec. 1917.

[16] Southern Cross, 1 Dec 1916.

[17] Kildea, ‘Paranoia and prejudice’, p. 158.

[18] Kildea, ‘Paranoia and prejudice, p. 57.

[19] Smith’s Weekly, 24 Oct. 1936.

[20] The Catholic Press, 13 Dec. 1917.

[21] L.F. Fitzhardinge, The little digger 1914-1952 (Sydney, 1979), p. 286.

[22] Kildea, ‘Paranoia and prejudice’, pp 160-1.

[23] Kildea, ‘Paranoia and prejudice’, p. 161.