Illustration 1: The Lady Kennaway Earl Grey ship departure on the 11th of September 1848 arrived on the 6th December 1848 Port Philip available at: https://www.geni.com/projects/Earl-Grey-Irish-Female-Orphans-in-Australia/15952

Introduction:

This section of the website examines the Irish Emigrant experience of education in Australia during the period 1788-1918.The path of Irish Orphans from Ireland to Australia and their educational experience is mapped by many different sources. The historian Kay Moloney Caball examines female orphans and the Earl Grey Scheme. The Earl Grey Emigration Scheme was introduced in 1848 the aim of this scheme was to reduce overcrowding in Irish workhouses during the famine. Some of the Earl Grey Orphans could read and write others were unable to. From the research it is hard to determine whether some of the orphans were educated in their first language Irish and had no English. However, it is clear than the education received by both orphans in Ireland and Australia was of a very low standard. A brief account of the lives of two orphans Mary Griffin and Bridget Ryan who were both Roman Catholics is provided. Mary Griffin was unable to read and write and Bridget was educated by French nuns in Ireland. Their life paths upon reaching Australia are very similar. The Institute for Destitute Roman Catholic Children was also established, this orphanage was set up to deal with the problem of Irish children who were orphaned by their parents, their parents were mostly convicts. Life in this orphanage was difficult and the conditions were poor. These orphans were educated in the orphanage but labour was clearly more important. The majority of those who participated in the Earl Grey Scheme did not receive any education upon reaching Australia they found jobs and they were married within a very short period of time. Some were also housed in Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks in an immigrant depot. The historian Gary Crockett is the curator of an exhibition at the Sydney Living Museum that examines the treatment of Irish orphans at Hyde Park Barracks. There are similarities between the orphans transported under the Earl Grey Scheme and the orphans that lived at Hyde Park Barracks and in the Institute for Destitute Roman Catholic children. From examining the records of the orphanage it is hard to determine if any of the orphans from the Earl Grey Scheme were in the orphanage in Parramatta. Although it is unclear what education the orphans at Hyde Park received they were also forced to work like the orphans at Parramatta. All parties were subject to hard labour in Australia and it is evident that even the education was based on teaching and preparing the Irish orphans for the labour market ‘mostly uneducated, unwordly and unused to domestic service, the orphans relied on protective officials to negotiate their place in the labour market’. [1] The girl orphans were described as disinclined to learn with ‘dirty and idle habits’[2] by a Sydney official. In the Sydney morning herald the Irish orphans were described as ‘ignorant creatures, whose knowledge of household duty barely reaches to distinguishing the inside from the outside of a potato, and whose chief employment hitherto, has consisted of some intellectual occupation as occasionally trotting across a bog to fetch back a runaway pig’.[3] From the evidence it’s easy to see that hard labour took precedence over education from Irish orphans during this period of Australian history and the life chances of the Irish emigrants were limited due to their lack of education.

The Earl Grey Scheme:

The Earl Grey Scheme was an important part of the Irish emigrant experience. According to Moloney Caball during the time of the famine in Ireland workhouses where overrun with young children whose parents had died or were no longer able to care for them. Meanwhile in Australia a lack of ‘domestic servants were causing very great discomfort in Melbourne’.[4] In Westminster the select committee on Poor Laws (Ireland) was examining the problems of ‘poverty, destitution, evictions, emigration and the overcrowding of workhouses caused by Famine.[5] British Parliamentary Papers on Ireland are available from http://www.dippam.ac.uk/eppi/eppi_lc_subjects/2354. The conditions in Ireland and the lack of labour supply in Australia led to the establishment of the Earl Grey Scheme.

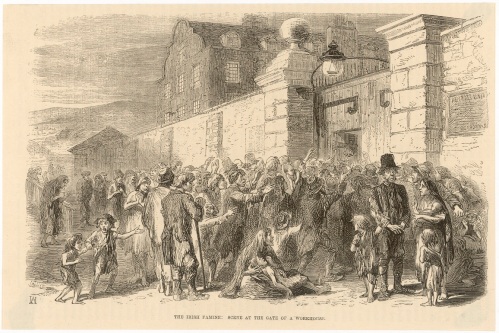

Illustration 2: Image of people gather outside a workhouse in Dublin available at: http://www.findmypast.ie/articles/world-records/full-list-of-the-irish-family-history-records/institutions-and-organisations/dublin-workhouses-admission-and-discharge-registers-1840–1919

Moloney Caball notes that Edward Senior the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner saw emigration as a solution to relieve overcrowding in the workhouses. Edward Senior suggested that ‘persons aged 13 or 14 to 18 or 19, especially girls’ should be chosen to emigrate under the Earl Grey Scheme.[6] Moloney-Caball states that in February of 1848 in order to fix the labour shortage in Australia ‘a free passage to New South Wales should be offered to certain classes of orphans of both sexes in Ireland between the ages of 14 and 18’.[7] By March the Earl Grey scheme was established and it aimed to select ‘young orphan females between 14 and 18 years of age who would be sent as emigrants to the Australian colonies, where, it was hoped they would in time become the wives of settlers’.[8] The Geelong Advertiser also provides a description of the orphans, the newspaper states that the orphans were to be accompanied by teachers and ‘will be instructed in conformity with their respective creeds-meaning, we presume, the Protestant and Roman Catholic creeds’.[9] This highlights the role of Religion played in the education of Irish orphans. The Geelong Advertiser also notes that the colonists were looking for ‘those whose education and moral religious training afford a reasonable guarantee that they will become active and useful members of a society’.[10] The Geelong Advertiser also highlights that the Emigration Commissioners would only select orphans whose ‘education has been attended to’.[11] The Orphan database provided by Moloney-Caball shows the educational record of the Kerry girls before they left for Australia. The majority of the girls were Roman Catholic and small proportion were Church of England. Records for the eighty Kerry girls recorded show that only nineteen of them could read and write, five of them could just read, forty of them couldn’t read and write and there are no records returned for sixteen of them. From the evidence presented above there is a contradiction here between the primary and secondary source. The primary source the Geelong Advertiser states that the colonists would only choose orphans who had been educated but the records from the secondary source The Kerry Girl’s show that a large proportion of the orphans could not read or write.

According to Moloney-Caball the Earl Grey Scheme was well organised there was a Surgeon, School Mistress and a religious instructor on board each ship. School hours were fixed by the religious instructor and teachers were paid a gratuity of no more than £5 if they had performed their duties correctly. It is unclear what the curriculum on board these ships was. On arrival the records of the Kerry girls show that most of these girls have received little or no education. Some started work straight away while others were housed in places such as Hyde Park Barracks here they awaited work and their days were occupied by chores and there is no evidence to suggest that they were educated at Hyde Park. The historian Gary Crockett from the Sydney Living Museum argues that the orphans were treated as cruelly at Hyde Park ‘the orphan girls were all disposed of, and sent away as fast as they could be disposed of’.[12] Once married the poor education the girls had received prior to going to Australia ‘militated against them in their new homes with growing children’.[13] Settling in gold fields Irish emigrants sent their children to diggings here parents paid a small fee for their children’s education but the standard of education was very poor. As Irish emigrants moved from goldfield to goldfield it was difficult to rely on teachers to turn up. Fathers were often too tired after a long day of hard labour to educate their children. The mothers some of whom who had come to Australia under the Earl Grey scheme where uneducated ‘if a mother on a station or farm could not instruct her children, education was rarely possible and though some older children may have helped the younger ones, few would have had any formal assistance’.[14]

The Kerry girls:

Moloney Cabball states that ‘we can see that while none of the orphans achieved huge material success they enjoyed moderate prosperity and

Illustration 3: A photograph of Bridget Ryan in later life. Taken from the Kerry Girls, p.36

it was as one generation succeeded another that their descendants prospered’.[15] This is evident through the stories of two Kerry girls Mary Griffin and Bridget Ryan.An account of their lives is given in the text ‘The Kerry Girls’. Upon her arrival to Australia it is noted that Mary Griffin could not read or write. The text notes an important point, Irish could have been Mary’s first language and maybe this is why she was unable to write in English. Mary is described eras ‘lucky’ as she was taken to Australia by Surgeon Charles Strutt who carefully vetted the applicants who Mary was being sent to work as a servant.There is no evidence to suggest that Mary received any further education upon reaching Australia. Upon reaching Australia, Mary was employed by a landowner called William Grogan . Within a year Mary was married to William Dixon who also worked on Grogan’s land. Bridget was selected from a workhouse in Listowel by Lieutenant Henry. Upon her arrival she claimed she was from Bruff Co. Limerick and she could read and write and was educated by ‘French nuns’ in Ireland. Like Mary, Bridget was employed upon reaching Australia and was married shortly after her arrival. There is also no evidence to suggest that Bridget received any other education after arriving in Australia.

The Roman Orphan School:

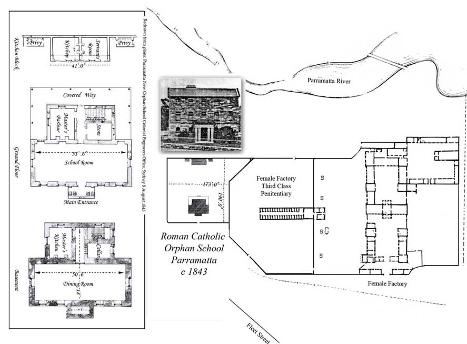

The Institute for Destitute Roman Catholic Children was an orphanage set up in New South Wales. In 1859 the institute was renamed the Roman Orphan School in 1859 when the orphanage was taken over by the Sisters of the of the Good Samaritan. The orphanage was set up following increased arrivals of ‘Irish Catholic convicts’. Prior to this there was a female orphan school built on Arthur’s hill in 1818 and was ‘Protestant in administration’. In 1844 the New Orphan School opened at Parramatta and 113 children were transferred there from temporary accommodation.

Illustration 4: The New Orphan School opened in Parramatta in 1844. Image available at http://www.parragirls.org.au/roman-catholic-orphan-school.php

Daily Routine in the Orphanage:

The orphanage had three storeys and there was a schoolroom in the basement. The orphans were educated by three teachers one for girls, one for boys and one for infants. The older children worked on the farm or in the laundry room. the conditions in the orphanage were poor and it was the subject of many government reports. The children’s daily routine consisted of praying, schoolwork and hard labour. Throughout the summer the children would get up a 6am say their prayers and work till there breakfast at 8. After their breakfast they said more prayers, do some school and then they worked till the evening had their dinner and went to bed. In the orphanage ‘emphasis was placed on religious instruction, basic education and training with the children required to carry out domestic duties including kitchen work, cleaning, laundry, woodcutting and farming’.[16] To cover the running costs of the orphanage the children had to do six days of unpaid labour a week doing tasks such as sewing, washing, cooking and cleaning. According to the Parramatta website by the 1860’s the orphanage was modelled on the ‘Magdalene Laundries of Ireland’ and laundry work became the main source of income for orphanages.[17] From the evidence it is clear to see that the labour was more important than education for the orphans.

Illustration 5: Plans for the Roman Catholic Orphan School made in 1843, image available at: http://www.parragirls.org.au/roman-catholic-orphan-school.php

Better life in Australia:

The Earl Grey Scheme improved the lives of the Irish orphans by removing them from the workhouses during the Famine. If they had not emigrated to Australia they may not have survived the famine. However, their lack of education clearly impacted their lives in Australia they were the subjects of hard labour and were married off within a short period of time. The situation in the Hyde Park Barracks and the Parramatta orphanage was similar as their education in these establishments prepared them for a life of work. The brief account given of two Irish orphans given shows how similar their lives where despite the fact that one was educated and the other was not.

Further reading:

[1] Gary Crockett, ‘Irish Orphan Girls at Hyde Park Barracks’, available at:http://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/irish-orphan-girls-hyde-park-barracks

[2] Crockett, ‘Irish Orphan Girls at Hyde Park Barracks’, available at:http://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/irish-orphan-girls-hyde-park-barracks

[3] Trevor McClaughlin, ‘Lost Children in History Ireland’ available at: http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/lost-children/

[4] Moloney-Caball, K. ‘The Kerry Girls: Emigration and the Earl Grey Scheme.’p.63

[5] Ibid, P.63

[6] Moloney-Caball, K. The Kerry Girls, P.63

[7] Moloney-Caball, K. The Kerry Girls, p.64.

[8] Ibid, p.64

[9]Irish Orphan Emigration, ‘The Geelong Advertiser’, October 12th 1848, p.4 available at NLA, Trove:http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/93136412?searchTerm=irish%20orphan%20education&searchLim=

[10]‘The Geelong Advertiser’, October 12th 1848, p.4 available at NLA, Trove:http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/93136412?searchTerm=irish%20orphan%20education&searchLim=

[11]The Geelong Advertiser’, October 12th 1848, p.4 available at NLA, Trove: http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/93136412?searchTerm=irish%20orphan%20education&searchLimit=

[12] Crockett, ‘Irish Orphan Girls at Hyde Park Barracks’ available at:http://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/irish-orphan-girls-hyde-park-barracks

[13] Moloney-Caball, K. The Kerry Girls, p.143.

[14] Ibid, p.143.

[15] Moloney-Caball, K. The Kerry Girls, p.144

[16] Author unknown, ‘Parramatta Roman Catholic Orphanage’ available at: http://www.parragirls.org.au/roman-catholic-orphan-school.php. (3rd, April,2017)

[17] Ibid