Photograph by Lieutenant Ernest Brooks of ANZACs in charge of working Turkish soldiers, Gallipoli, 1915. Source: Imperial War Museum, Catalogue Number Q 13829

On 25 April every year in Australia and New Zealand, the two nations join together to celebrate those who sacrificed themselves for their countries in times of war and horror. This date was chosen to commemorate the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) troops who landed on the beaches of Gallipoli to fight the Turkish on that day in 1915. What is often not remembered throughout these commemorations are the Irish soldiers who not only fought for the British Army but the ANZACs themselves. There was a significant loss of Irish life in the Battle of Gallipoli in Turkey and the deaths of these men helped to shape Australian identity and nationalism from its conceptions at this and other battles. Much like many other immigrants, the Irish that were in Australia during the First World War were people searching for better lives for themselves in a new country, hoping that the promises of jobs that they had received in letters from relatives already out there would work out. Instead, many of these fresh Irish immigrants would be persuaded to join the Australian war efforts and join the ANZAC forces.

Irish ANZACs

According to the ‘Irish ANZACs’ database hosted by Ireland’s national public service broadcaster Radió Teilifís Éireann to commemorate 100 years since the Gallipoli campaign, more than 6,600 Irish soldiers signed up to the ANZACs during World War One, with 854 of them fighting on the beaches of Gallipoli.[1] Jeff Kildea, a leading historian of the Irish ANZACs has stated ‘in the First World War, the Australian Irish played their part in building that most enduring edifice of Australian national identity, the ANZAC tradition’.[2] Kildea’s statement shows that, although at this time there was propaganda in Australia that the Irish immigrants were not signing up and helping the Australian army at all, there was in fact a large number of soldiers who fought, helped and ultimately gave their lives for their adopted land.[3] Evidence of the roles played by the Irish ANZACs at the Battle of Gallipoli comes in a variety of forms including the service records, memoirs and diaries of soldiers like Thomas Noonan of Co. Limerick, and David O’Dwyer, of Co. Wexford.

Although Gallipoli featured many Irish soldiers fighting on behalf of the British Army, hundreds of Irish also stormed the beaches with the Australian and New Zealand ranks. While the first ‘global’ war took place, there were also huge political moments taking place in Ireland, with the 1916 Rising events commencing in Dublin as Padraig Pierce read the proclamation.[4] As the First World War progressed and it became clear that ill-fated campaigns like that Gallipoli were becoming slaughtering grounds for the British and Australian forces, both Irish and Australian soldiers began to sense an unease at the British Empire over the lack of planning and the unnecessary horror of Gallipoli, creating a very confusing time for Irish Australians. Jeff Kildea states in his ‘The Irish at Gallipoli’ Historyhub.ie podcast with University College Dublin that Irish soldiers who fought for the ANZACs at this time were seen as traitors to the Irish fighting at home, as these men were in fact fighting for the British in their adopted home of Australia.[5]

‘The Foggy Dew’

Feeling of disgust towards these men was captured by Canon Charles O’Neill in his 1919 poem ‘The Foggy Dew’, set to an older traditional tune. The poem chronicles the Irish revolutionary struggle, and contrasts two types of Irishmen: those who fought in Ireland for Ireland and the thousands who fought abroad for the British Empire so that small nations like Ireland ‘might be free’. The song contains the lines:

‘Right proudly high over Dublin Town they hung out the flag of war

‘Twas better to die ‘neath an Irish sky than at Suvla or Sud-El-Bar

and from the plains of Royal Meath strong men came hurrying through

While Britannia’s Huns, with their long range guns sailed in through the foggy dew

‘Twas England bade our wild geese go, that “small nations might be free”;

their lonely graves are by Suvla’s waves or the fringe of the great North Sea.

Oh, had they died by Pearse’s side or fought with Cathal Brugha

Their graves we’d keep where the Fenians sleep, ‘neath the shroud of the Foggy Dew’.[6]

Suvla refers to the Suvla Bay, in the Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey, while Sud-el-Bar (Sedd el Bahr) refers to Dardanelles fort, a major British position in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign of 1915-1916.

It is important to remember that this song was written in Ireland in 1919, at a time of political unrest and change. On 21 January 1919, the Irish Republican Army shot dead two policemen in county Tipperary, an action that marked the beginning of what is now known as the War of Independence. In Australia, Irish Australian veterans of the First World War began to feel that they would be no longer welcome back at home in Ireland and were ashamed at how their fellow countrymen were acting. Malcolm Campbell has argued that as both Ireland and Australia began to become more hostile towards outsiders in the early twentieth century – and the focus shifted towards the disgust at traitors and people who had not fought – both countries were sent into a period of heightened national chauvinism. With that, Irish immigrants became disillusioned with their old homelands and many turned their back in shame, claiming less often that they were from the tiny isle.[7]

Thomas Noonan (1893-1915)

Framed photograph of Thomas Noonan in uniform. Source: Europeana, 1914-1918

Conditions for Irish ANZACs were the same as soldiers on many sides of this battle, with food being rationed and soldiers being limited to one litre of water a day to wash themselves, clean and drink.[8] Many soldiers were living day-to-day unsure of what the next move was or whether they would survive the next 24 hours that they faced. One such soldier was a young man named Thomas Noonan who sent letters home and kept diaries during his time in Gallipoli, writing about his experience in great detail.

According to his nephew Michael who donated his papers to the Europeana 1914-1918 archive, Thomas was born in 1893 in Ballyguy, Murroe, Co. Limerick, Ireland. He worked in McBerny’s shop on Thomas St. in Limerick and rowed with Limerick Rowing Club. He spent a year working in the mines in Wales before returning home to Ireland. Like many other Irish emigrants, he was ‘brought out’ to Australia by a relative, in this case, an uncle who sent the fare for Thomas to emigrate to Sydney, where he had a job for him. Thomas arrived in Sydney around June/July 1914 but the job never materialised, and so he joined the 13th Battalion (Australia).[9]

In one of his letters home to Ireland, Thomas wrote about the danger, describing an incident where he was playing cards with a fellow soldier when a shrapnel bullet ‘came down within a couple of inches’ of his knee. Later on another letter home, he wrote of being in the hospital for three to four months due to shrapnel injury but states that he could not wait to get back out to the front line.[10] He also wrote in his pocket diary of the horrible conditions the ANZACs had to fight in, with one entry stating that as he headed towards the front line once more, he and his comrades were told to sew white armbands onto their sleeves and to the backs of their uniforms as it was so difficult to identify who was who due to the fog and terrible weather conditions.[11] That would unfortunately be 23-year old Thomas’s last diary entry as he was killed in action on 9 August 1915.[12] Like many other Irish men who came to Australia in the hopes of making new lives for themselves, Thomas Noonan had made the ultimate sacrifice for their adopted homeland. Like many others, he contributed to creating the ANZAC pride that is still so prevalent in Australia and New Zealand to this day.

After the Gallipoli campaign ended and all of the soldiers had been evacuated from the shores, it became obvious to the Irish soldiers that had fought and were now dealing with the repercussions of seeing and taking part in such a horrible, life-altering event that they would not be able to go back to living normal lives. What became most common for these men was that after surviving those travesties, they would were immediately sent to the Western front to engage in more combat.

David O’Dwyer

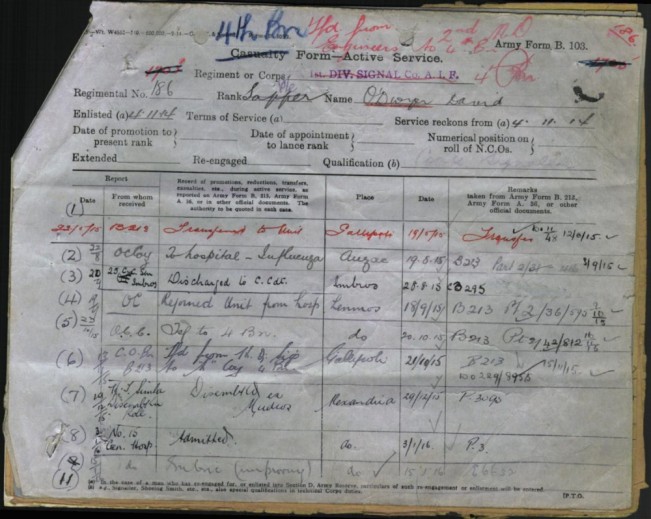

David O’Dwyer’s casualty form (National Archives of Australia). Source: RTÉ Century Ireland 1913-1923: Gallipoli

Not having sufficient time to recooperate after Gallipoli, many soldiers who were injured tried to stay as far away from any more battles as possible. One such ANZAC soldier was David O’Dwyer, a 34 year old unmarried fireman from Co. Wexford who signed up in 1915 and ended up in Gallipoli, where he caught influenza.[13] David did not die from his illness but the little action that he had seen scarred him enough that he would spend the next several years of his life in and out of thirteen different hospitals with various illnesses as well as a handful of issues with the ANZACs over absences without leave. Over the space of four years, O’Dwyer had reportedly suffered from so many traumas over the war that the Army eventually discharged him from leave and he went back to Melbourne, where he spent the rest of his life quietly. O’Dwyer was not the only soldier to suffer with these reactions after going to the bloodbath that was Gallipoli and it is clear to see that, just like many Australian and New Zealanders, the Irish soldiers that fought for the ANZACs and made it out alive, experienced their own pain and suffering, giving up their own health in return for fighting for the country that they had come to in search of a better life.

The invasion of Gallipoli was not a success. Rather, it was a stark reminder to the British empire, it allies and former colonies like those on the Australian continent that even though they were offering their lives up for their nation, the government at the time allowed thousands of men to die due to their bad planning and unpreparedness. These men, who bravely marched into battle, have been commemorated for hundreds of years in Australia, celebrating the legacy and pride that they have in their ANZACs, yet in Ireland, it is only as the battle reached its centenary that celebrations and commemorations were put in place. In 2014, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Charles Flanagan, and the Australian Ambassador to Ireland, Ruth Adler, launched a database in collaboration with the Global Irish Studies Centre of the University of New South Wales that has compiled and collected all of the information and documents that have been found relating to Irish soldiers who fought with the Australian and New Zealand armies.[14] This will allow the Irish men who fought and died for these countries not only to be remembered on Anzac celebrations in that continent, but also to finally get the respect they deserve from the Irish public and from Irish historiography. It is now clear to see, in contrast to the articles that were circulated at the time stating that the Irish were not contributing to the war efforts of the ANZACs, that the Irish played a pivotal role in the military action in Gallipoli, helping to forge out the new Australian identity and pride that this group of ill-fated soldiers prompted.

REFERENCES

[1] ‘Irish ANZACs’, Radió Teleifís Éireann, Century Ireland, 1913-1923: Gallipoli, 2015, (https://gallipoli.rte.ie/guides/irish-anzacs/) (8 Apr. 2018) The Century Ireland project and resources were created by researchers at Boston College Ireland and is funded by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht.

[2] Ibid

[3] ‘Irish in Australia “were not shirkers” in first World War’, Irish Times, 17 Oct. 2014, (https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/irish-in-australia-were-not-shirkers-in-first-world-war-1.1967446) (6 Apr. 2018)

[4] Frank Brennan, ‘The 1916 Rising: a view from Australia’, An Irish Quarterly Review, 105 (2016), pp 225-235

[5] Jeff Kildea, Podcast: The Irish at Gallipoli, historyhub.ie, 2015 (http://historyhub.ie/the-irish-at-gallipoli-by-jeff-kildea) (6 Apr. 2018)

[6] Charles O Neill, The Foggy Dew, 1919. See Labrini Gioti (Labri Giotto), ‘The Foggy Dew: processes of change in an Irish Rebel song’, Outreach Ethnomusicology – An Online Ethnomusicology Community, 2015 (https://o-em.org/index.php/fieldwork/62-the-foggy-dew-processes-of-change-in-an-irish-rebel-song) (4 May 2018)

[7] Malcolm Campbell, ‘Emigrant responses to war and revolution, 1914-21: Irish opinion in the United States and Australia’, Irish Historical Studies, 32 (2000), pp 75-92

[8] ‘Gallipoli and the Anzacs’, Australian Government Department of Veterans affairs, (https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/history/conflicts/gallipoli-and-anzacs) (4 Apr. 2018).

[9] Michael Noonan, ‘Thomas Noonan of Ballyguy, Co. Limerick, 13th Battalion (Australia) died at Gallipoli’, 2017, Europeana 1914-1918, (https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/record/2020601/contributions_4436.html) (4 Apr. 2018).

[10] Thomas Noonan letters, Europeana 1914-1918, (https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/record/2020601/contributions_4436.html)

[11] Diary of Private T. Noonan, No. 204, B Company, 13th Battalion, Australian Imperial Forces, Entry for Friday 6 August 1915, Europeana 1914-1918, (https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/record/2020601/contributions_4436.html#&gid=1&pid=47)

[12] Copy of death notice, Europeana 1914-1918, https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/record/2020601/contributions_4436.html#&gid=1&pid=34l)

[13] Mike Cronin ‘ANALYSIS: Who were the Irish Anzacs at Gallipoli?’, Radió Teleifís Éireann, Century Ireland, 1913-1923: Gallipoli, 2015, (https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/analysis-who-were-the-irish-anzacs-at-gallipoli) (8 Apr. 2018)

[14] Press release: ‘Minister Flanagan to launch database of Irish serving in Australian forces in the First World War’, 16 October 2014, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (https://www.dfa.ie/news-and-media/press-releases/press-release-archive/2014/october/flanagan-launch-anzac-irish-database/); Irish Anzacs Project, UNSW Arts & Social Sciences (www.bit.ly/1rAOjK3)