Lithograph caricature of Charles Gavan Duffy, 1874. Source: State Library of Victoria

The Irish transported Australia for political reasons – such as the Young Irelanders William Smith O’Brien and John Mitchel – have been over-represented in the historiography despite their few numbers.[1] Nevertheless, a majority of these immigrants were not rebels: they were a part of the British imperial order, involved in the ruling of Australian colonies including Victoria, and were integrated in their political system and institutions. Charles Gavan Duffy (1816-1903), on whom the focus is here, both paradoxically contested against and participated in this order. His contradictory character caused uproar among his contemporaries. As Steven Knowlton has shown, historians share similar oppositions: Doyle has described him as ‘radical land reformer’, while Clark has considered him as a ‘bourgeois liberal’.[2] However, according to his memoir, My life in the two hemispheres, which will be the core of this study, Duffy was a part of the British colonial governance of Victoria, where the Anglo-Irish were becoming the major political, economic, and social élite.[3] All of this highlights an interesting aspect of Irish involvement with and impact upon colonial politics in Victoria. Indeed, Duffy was Premier of this colony from June 1871 to June 1872, the period which will be explored here, exploring why his character may have appeared different to that of other members of the Irish political class. Nonetheless, his gradual integration into the imperial system of governance along with the reforms he tried to apply show that he also belonged to this group of Irish at the heart of power.

‘Nothing was done which needs to be repented’

Limited to his public life, very little objectivity is evident in Duffy’s memoires. For instance, in the extract about his time in office as Premier, there is no description of his fervent Catholicism. This is nonetheless an essential element in understanding his personality and some of his political actions, as it excluded him from the Protestant Anglo-Irish élite.[4] His memoires were written almost twenty years after the events they described, and published exactly one century after the 1798 Irish rebellion. Along with the fact that he appeared relatively proud of himself, the time difference accentuates this subjectivity. Thus, according to himself, his appraisal of his own actions as head of the government was that

No man could utter a just reproach. … A quarter of century after the events of that day, I look back on them with the confident assurance that nothing was done which needs to be repented, or which I would not repeat if the occasion occurred.[5]

Duffy’s My life in the two hemispheres does not accurately depict his failures or his weaknesses concerning actual events – like ‘The Land Question, which had ‘been [his] care from the beginning, [but] had been ruined by maladministration’.[6] Furthermore, in compiling his memoires, he used press extracts to illustrate his accounts, which were either from the ‘pro-government’ newspaper, the Spectator, or anti-Irish papers like the Argus. But these always appear to favour of his actions.[7] In this context, extracts from other contemporary newspapers will be used to approach a more objective point of view; overall, there is consensus that Duffy was well integrated in the governance of Victoria.

Nonetheless, Duffy remained a major historical character back in Ireland, with an important political background and involvement. This had important implications during his time as Premier of Victoria. He was a former member of the Young Ireland movement, a republican, cultural, and ‘romantic’ nationalist movement that sought Irish independence from the British Empire. According to the newspaper that he founded, the Nation, his Australian policy would be a continuation of the struggle for more autonomy.[8] This point was emphasised by his opponents who used his controversial past to support their positions, such as when they claimed that Duffy desired to ‘dismember the British Empire’.[9] The Premier of Victoria used his experience as a member of Young Ireland to justify his integrity and to convince his fellows. The importance of his past, which was a sort of ‘revolutionary’ one, differentiated him from the rest of the political élite, British or Irish, but was no longer justified in the 1870s.

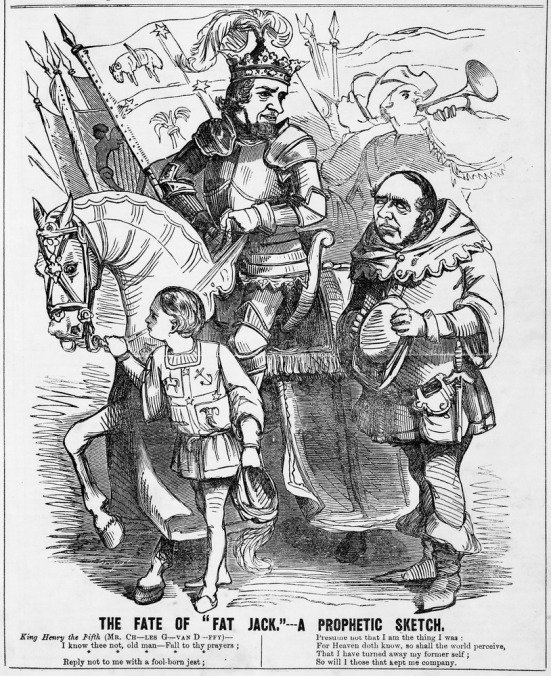

Caricature of Duffy arriving in Victoria, 1856. Source: State Library of Victoria

Duffy had changed, adopting a less radical position towards the Empire and British presence. For instance, he was opposed to the Governor about abuses of power, but it was more an anecdotal issue rather than an opposition to his highly symbolic function. According to himself, even when he was in Australia, he was ‘still an Irish rebel to the backbone and to the spinal marrow … [he] added … that [he] was a Radical reformer, but [he] was no more a Red Republican’.[10] In this controversial declaration, he reiterated his oppositional experience, but admits to not be against the idea of a monarchy or an empire any longer. Aside from his persona as a rebel, he was also perceived as a reformer of the public life by the public opinion.[11] While the rest of the Anglo-Irish tried to hide their Irish ‘distinctiveness’, Duffy seems to have been proud of his identity. Even if he remained a key figure of the Irish cause, associating with an image of adversary, he was no longer an opponent of this order and was integrated within it when he became Premier of Victoria.

A member apart from the ruling elite?

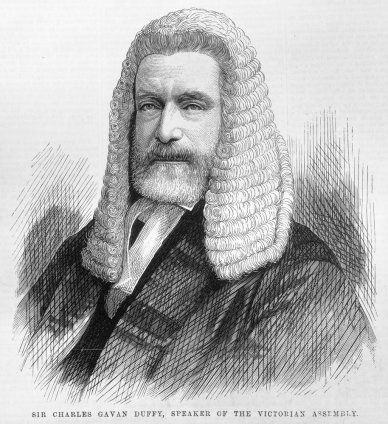

Illustration of Charles Gavan Duffy as the Speaker of the Victorian Assembly, 1877. Source: State Library of Victoria

Duffy’s colonial career, as well as his important involvement in Australian politics in general, denotes the fact that he was wholly integrated within colonial governance. Shortly after his landing at Melbourne in February 1856, he was elected Member of the Parliament thanks to both important Irish popular and liberal ‘party’ supports, which gave him the necessary property qualification.[12] It proved too that he had a secure base amongst the Irish diaspora.[13] From 1858 to 1859, and from 1861 to 1863, he was Minister for Lands in John O’Shanassy’s governments, and he tried to pass a reform in favour of small landowners, which was unsuccessful.[14]

By becoming Premier of Victoria in June 1871, Duffy became one of the most important characters in a ‘model’ Australian colony, within a more ‘developed’ and ‘democratic’ political system, where an Irish Catholic Premier could be appointed. Added to the fact that he also possessed important parliamentary experience from London, he had a good knowledge of parliamentary procedures and of the rites of the system.[15] Westminster remained the model for this, but was poorly imitated by the colonial representative assemblies. However, Duffy’s expertise was different from the rest of the Victorian political élite whose members were predominantly unaccustomed to parliamentary life.[16]

Duffy was not the only ‘son of Erin’ to be implicated in Victoria’s politics. With a peak of influence from the Gold Rush period to the 1880s, the Irish, and especially the Protestant Anglo-Irish, were major constituents of the ‘imperial class’. While the majority of this community was uneducated, the political élite attended some prestigious educational establishments in Britain and Ireland, especially Trinity College Dublin.[17] They constituted a strong group of landowners, and they were convinced by the imperial ideal. This élite did not appear to encounter any major integration problems in the Australian colonies, contrary to the rest of the Irish Catholic community who knew a certain Anglo-Saxon hostility.[18] They were fully integrated in the colonial political system. Many of them were present in the Legislative Council for instance, as well as other administrational posts.

To a lesser extent, the Irish Catholics were also involved in this. Nonetheless, a kind of mistrust and sectarianism towards the ‘Papists’ remained, with fears of a Fenian conspiracy. This in part developed after an attempt of assassination of the Duke of Edinburgh in 1868.[19] This is illustrated by Duffy in his last years in office, with his Education bill, as well as his patronage of Louth man John Baptist Cashel Hoey as secretary to the Agent-General, decisions which were argued to have favoured the Catholics. Nevertheless, he shared many common things with the Protestant élite, which could often appear totally different from him. Like all other politicians, he had to face the opposition of his fellow Irish, namely the conservative O’Shanassy, originally of Co Tipperary; this illustrates that ‘Irishness’ was not the only reason for political alliances with or against Duffy.[20]

Increasing criticisms and end in office

Duffy’s political experience made him surprisingly more able to manage colonial affairs than his fellows. But this kind of ‘superiority’, along with his fervent Catholicism, made him unpopular within the Protestant community. However, he had good relations with some of them. Unlike the majority of them – who did not know the ‘accurate’ political organisation – he knew the ‘right’ procedure to use, the Westminster one. He was a hard-working legislator and was involved in various Commissions, Boards of Inquiries, or Committees.[21] These were additional arguments in favour of his perfect integration into colonial governance. Finally, like the other politicians of his time, Duffy attended many banquets and public civic events, where he was apparently highly favoured.

Even though his policies in Victoria were mainly about Victorian problems, the issues managed during his term were relatively similar to Irish ones, namely education, land propriety, and the end of sectarian discrimination. Being perceived as a pro-Catholic politician, however, made him generallty unpopular amongst the Protestants. One of his most important campaigns was for Victoria’s ‘industry’, particularly through the creation of tariffs between the Australian colonies. This was totally contradictory with his economic position in Ireland, which was pro-Free Trade. According to him, this shift occurred to defend Victoria’s prosperity. With regards to the tariffs, which were controlled by the Imperial government, an ‘inter-colonial conference of the Australian governments’ was organised in Melbourne. Having negotiated with Duffy, London finally agreed and passed the law. This proved that the Premier of Victoria was well and truly integrated in the imperial system of governance – that he acted within it, not against it. This shift from its past proves likewise that this Irishman was integrated in the political élite of Victoria which acted for the colony, and not only for Ireland. Indeed, the latter felt themselves both British and Australian: they defended Australian interests within the Empire. Like them, Duffy asked for more liberties and autonomy in favour of the colony.

George H. Jenkins, sketch representing the Parliament of Victoria, 1886. Source: State Library of Victoria

During his last years in office, when the education question raised strong opposition against him, Duffy remained fully integrated in Victoria’s ‘British’ system. He created controversies because he it was felt that he would apply policies that would favour the Catholics, evidenced by his patronage of Hoey which led him losing his office. This was due to the conservative élite, sectarian and afraid of his popular support. Nonetheless, he obtained a kind of ‘consecration’ when he received a knighthood from the Governor, the most symbolic representative of the monarchy. What could be more contradictory than a former ‘rebel’ and republican honoured by the representative of the Queen in Australia for his actions in favour of the British order? This last point illustrates that Duffy was a member of an Anglo-Irish political élite, which was wholly integrated in the imperial system of governance – especially during his office as Premier. With strong parliamentary experience, this Catholic and former Republican would appear as different to the Victoria’s political élite. Because of his peculiar Irish past, Duffy remained different from the rest of the Irish who were involved in Australian colonial politics. But like them, he stayed strongly involved in colonial ruling.

REFERENCES

[1] Patrick J. O’Farrell, ‘The Irish in Australia and New-Zealand, 1791-1870’, in W.E. Vaughan (ed.), A New History of Ireland V, Ireland under the Union, 1801-1870 (Oxford, 2010), pp 663-664.

[2] Steven R. Knowlton, ‘The enigma of Sir Charles Gavan Duffy: looking for clues in Australia’, in Eire-Ireland, 31 (1996), pp 189-190.

[3] Charles Gavan Duffy, My life in the two hemispheres, vol II (London, 1898), pp 321-346. Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/mylifeintwohemis02duffuoft) (8 April 2018).

[4] Knowlton, ‘The enigma of Sir Charles Gavan Duffy’, p. 191.

[5] Duffy, My life in the two hemispheres, p. 321.

[6] Duffy, My life in the two hemispheres, pp 321-346.

[7] The Advocate, 11 Nov. 1871, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/170154785?searchTerm=Duffy%20&searchLimits=l-title=792|||l-decade=187|||l-year=1871|||l-month=11) (8 April 2018).

[8] The Nation, 9 Sept. 1871, cited in Joy E. Parnaby, ‘Charles Gavan Duffy in Australia’, in O. MacDonagh, W. F. Mandle and P. Travers (eds), Irish culture and nationalism, 1750-1950 (New York, 1983).

[9] Duffy, My life in the two hemispheres, pp 325-326.

[10] Duffy, My life in the two hemispheres, pp 133-134.

[11] Manning Clark, A history of Australia: the earth abideth for ever, 1851-1888 (Melbourne, 1978), p.110.

[12] Patrick James O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia (Kensington, 1986), p.134.

[13] Patrick Maume, ‘Duffy, Sir Charles Gavan (1816-1903)’, in J. McGuire and J. Quinn (eds.), Dictionary of Irish Biography III (Dublin, 2009), p.507.

[14] Joy E. Parnaby, ‘Duffy, Sir Charles Gavan (1816–1903)’, in Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/duffy-sir-charles-gavan-3450/text5265) (7 April 2018).

[15] Joy E. Parnaby, ‘Charles Gavan Duffy in Australia’, in O. MacDonagh, W. F. Mandle and P. Travers (eds.), Irish culture and nationalism, 1750-1950 (New-York, 1983).

[16] Beverley Kingston, The Oxford history of Australia, III, Glad, confident morning, 1860-1900 (Oxford, 1989), pp 237-242.

[17] Manning Clark, A history of Australia: the Earth Abideth for ever, 1851-1888 (Melbourne, 1978), p.109.

[18] O’Farrell, ‘The Irish in Australia and New-Zealand, 1791-1870’, pp 674-676.

[19] Kingston, The Oxford history of Australia, pp 125-126.

[20] S. M. Ingham, ‘O’Shanassy, Sir John (1818–1883)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 5 (1974), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/oshanassy-sir-john-4347/text7059) (23 May 2018).

[21] Steven R. Knowlton, ‘The enigma of Sir Charles Gavan Duffy: looking for clues in Australia’, in Eire-Ireland, 31 (1996), p. 196.