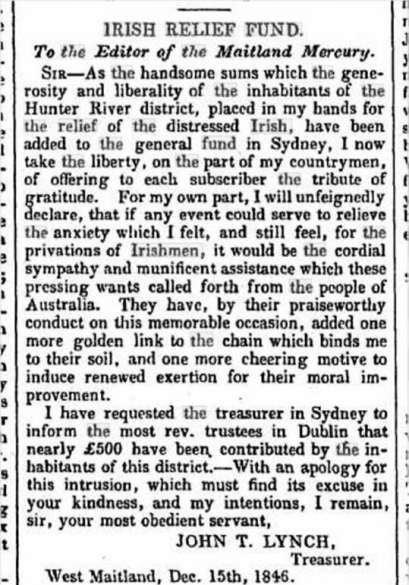

Letter from Maitland Irish Relief Fund treasurer, John T. Lynch, to the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 16 Dec 1846.

The Great Irish Famine of c.1845 to c.1852 affected almost every aspect of Irish life. Aside from the rampant starvation, disease and death, one of the most prominent effects was an increase in emigration levels resulting in an estimated one million people leaving the country. However, there is a general misconception within the Australian media concerning the number of Irish emigrants entering the colonies during the years of the famine as the majority of expatriates went to America.[1] Nonetheless, those who did manage to emigrate to the Australian continent under various sponsorship programmes such as the so-called Earl Grey Scheme, were successful in raising awareness about the difficulties being experienced in Ireland.[2] This led to the introduction of Famine relief funding efforts that increased general and political awareness in the Australia colonies of Irish issues. In 1846, the Sydney Chronicle was able to report that ‘the very handsome sum of £3,000’ had been raised less than a year after the start of targeted fundraising in New South Wales.[3]

It is quite easy to use contemporary commentaries in the newspapers to highlight the negative aspects of the Irish character; an attempt here will be made to highlight positive press portrayals of ‘Irishness’ like the ‘generosity and liberality of the Irish inhabitants’ extolled by a writer to the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser in 1846.[4] Newspapers that circulated throughout the colony of New South Wales in that year – the aforementioned Sydney Chronicle, Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, and Sydney Morning Herald – form the primary source evidence base for this investigation. While exploring these sources, several factors should be taken into consideration, including the political background of the newspaper.

The historiography concerning the influence of the famine in increasing general awareness of Irish issues in Australia is quite varied. There has been a recent surge in historical research concerning the Irish immigrant experience within Australia. However, in regard to the Irish famine, the majority of this research focuses on the famine orphan girls resulting from the feminist movement of the 1960s which aimed to uncover a female past and to ‘gender history’.[5] Nonetheless, the work of Michael Campbell and James Jupp serve as critical points of context for arguing that the responses of the Irish to the plight of ‘their starving countrymen at home’ reflected well on and were instrumental in creating favourable images of the community there.

Public meetings and subscriptions

In October 1846, a year after potato blight and consequent famine struck Irish shores, discussions began in New South Wales to consider the possibility of assisting the deteriorating condition of Ireland which was described as ‘destitute’ in the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser.[6] This newspaper was established in 1842 by Richard Jones who immigrated to Australia from Liverpool. Jones’s support of local movements is evident in his encouragement of a relief system for Ireland in New South Wales.[7] The introduction of a relief fund within Australia was not a new concept as a system had already been set in place in Melbourne to send money back to Ireland. Nonetheless, the newspaper’s editorial suggested that Jones was speaking collectively on behalf of the community stating: ‘The people of Maitland, we are glad to see, are about to follow the example of the inhabitants of Melbourne and Sydney. Arrangements have been made for holding a public meeting at the Court-house, East Maitland, on Monday next, for the purpose of raising subscriptions towards the relief of the sufferers from the famine in Ireland. We are sure that the inhabitants of the town and district will show that they are not less alive to the claims of their starving countrymen at home than our fellow-colonists to the southward have proved themselves to be.’[8]

Sir Charles Augustus Fitzroy, tenth Governor of New South Wales, 1855. Source: (Australian Dictionary of Biography)

This suggests a unifying form of concern about the deteriorating conditions in Ireland and an increasing sense of ‘Irishness’ relating to the relief efforts. While this was predominantly encouraged by the Irish settlers, it is evident from the source that many English settlers offered their sympathy to the plight of the Irish. As James Jupp has argued, this in turn led to an increase in the awareness of general and political issues of Ireland within Australia, directing the attention of political figures to consider Irish as opposed to solely Australian causes.[9] Indeed, Sir Charles Augustus Fitzroy, the tenth official governor of New South Wales during the years from 1846 to1855, was an avid supporter of the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser describing it as ‘one of the colonies leading newspapers’.[10] Thus, it is not surprising that the governor supported the ideologies of the newspaper.

The politics of Irish famine relief

The portrayal of the Irish relief system was frequently documented throughout the printed press which led to increasing discussions about a system being organised in New South Wales. The Sydney Morning Herald, a paper run by an English settler, John Fairfax, reported in October 1846 that ‘a public meeting took place at the Court House, Yass… for the purpose of aiding the Irish Relief Fund’. While the overall tone of the report was one of support for the fundraising drive, it did not encourage public contribution to the extent that was evident in the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, for example. Rather the focus was on the attitudes of several political figures who appeared to lack major concern over the issue of famine relief. The public meeting itself was portrayed as unorganised as ‘it did not take place until an hour or so after the appointed time, which was to be regretted, as many persons did not attend in consequence’.[11]

Information about the roles of key individuals was also supplied by such reports: the appeal in favour of the scheme, for instance was led by Cornelius O’Brien, a member of the Yass District Council since 1846 and a justice of the peace. Born in Ireland, O’Brien moved to Sydney in January of 1815 aboard the Marquis of Wellington.[12] However, those present at the 1846 Irish Relief Fund meeting were portrayed within the newspaper as offering little input. Nonetheless, the result was ‘a subscription list was opened, and we are happy to say, about £68 subscribed on the spot’.[13]

There is some contradiction concerning the involvement of Sir Charles Augustus Fitzroy.[14] The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the Rev. C. F. Brigstocke had sent a letter prior to the commencement of the meeting to apologise that he could not attend due to other engagements but ‘at the same time he offered his most cordial assistance towards collecting subscriptions to the funds.’ The poor organisation of the event is further illustrated by a revelation that the meeting had been scheduled on the same day as a ‘public meeting of the inhabitants of the district of Yass … for the purpose of considering the propriety of addressing the Governor [Sir Charles Fitzroy] on his arrival in the colony’.[15] The way in which the events are portrayed here suggests that the governor did not play an active role in encouraging the Irish relief system in October 1846. However, Fitzroy was one of the first political figures in New South Wales to become involved in the relief efforts by donating £10 pounds to the cause.[16]

Handsome sums

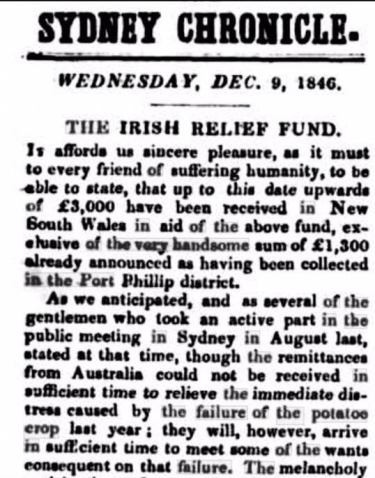

Fundraising efforts of the Irish Relief Fund. Source: Sydney Chronicle, 9 Dec 1846)

In analysing the perception and portrayal of Irish relief efforts in the press, a common trend emerges. It is evident that the ways in which the facts are presented reflect the political background of the medium. The Sydney Chronicle, for example was a Catholic newspaper that tended to positively reflect the scheme by commending the people of Sydney for their fundraising efforts. It provided information about the amounts raised ‘to this date upwards of £3,000 … exclusive of the very handsome sum of £1,300 already collected’. The newspaper also acknowledged reports coming from England and Ireland in which John Russell, the Lord of the House of Commons suggested that the failure of the potato crop in Ireland was set to continue.[17]

According to Malcolm Campbell, one quarter of the population in New South Wales was Irish-born by 1846.[18] Taking these figures into consideration, it is clear that the colonies publicity organs’ perception of Irish famine relief schemes were highly influenced by a sense of ‘Irishness’ already prominent or promoted throughout the region. While the Sydney Chronicle dealt primarily with commemorating the fundraising efforts of the general community, it appealed directly to the Irish populace by stating to those ‘who have not already contributed, to come forward to the aid of their fellow creatures in Ireland’. In doing so, the newspaper highlighted a sense of unity between the Irish populace in Australia and those who remained in Ireland. However, it does suggest caution when donating funds as several of the collections ‘in Bathurst and Yass have not yet come to the treasurer’s hands’.[19]

It is evident that reports of the Great Famine in Ireland were responsible for increasing general and political awareness of Irish issues in Australia during the long nineteenth century. While the focus here has been confined to the year 1846 in New South Wales, each of the newspapers mentioned represented the Irish famine relief fundraising schemes in a positive light, while simultaneously alluding to the perceptions of Irishness in the colonies. However, it is evident that these perceptions were reflective solely of the year and area which was analysed. In fact, it is interesting to note that newspapers in areas such as Van Diemen’s Land associated the fundraising activities of the Irish with the increasing level of crime throughout the region. Nonetheless, one can clearly state that the portrayal of the pitiful Irish cause in the Australia press was successful in contributing to a positive sense of ‘Irishness’, particularly in New South Wales.

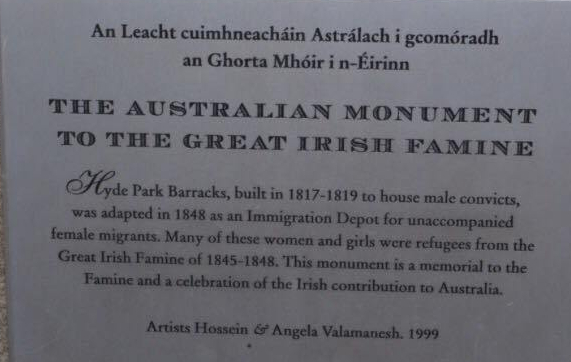

Famine memorial at Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney. Source: http://www.irishfaminememorial.org/en/about-monument/

REFERENCES

[1] Malcolm Campbell, Ireland’s new worlds: Immigrants, politics and society in the United States and Australia, 1815-1922 (London, 2008), p.4.

[2] Campbell, Ireland’s new worlds, p.58.

[3] Sydney Chronicle, 9 Dec 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31749417?searchTerm=the%20failure%20of%20the%20potato%20crop%20in%20ireland%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=dateFrom=1846-11-01|||dateTo=1846-12-15|||sortby=dateAsc)

[4] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 16 Dec 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove ((https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/686425?searchTerm=the%20Irish%20relief%20fund&searchLimits=dateFrom=1845-01-01|||dateTo=1852-01-01)

[5] Jeremy Black, Studying History (London, 2007) p.141.

[6] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 9 Sep 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/684600?searchTerm=the%20Irish%20famine%201846&searchLimits=dateFrom=1845-01-01|||dateTo=1852-01-01)

[7] Elizabeth Guilford, ‘Jones, Richard (1816-1892)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2(1967), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jones-richard-2281)

[8] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 9 Sep 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/684600?searchTerm=the%20Irish%20famine%201846&searchLimits=dateFrom=1845-01-01|||dateTo=1852-01-01)

[9] James Jupp, An encyclopaedia of the nation, its people and their origins (Cambridge, 2001), p.455.

[10] Guilford, ‘Jones, Richard (1816-1892)’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2 (1967).

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 Oct 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28649519/4092178)

[12] Peter Scott, ‘O’Brien, Cornelius (1796-1869)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2 (1967), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/obrien-cornelius-neal-2848)

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 Oct 1846.

[14] John M. Ward, ‘FitzRoy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1 (1966), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzroy-sir-charles-augustus-2049/text2539) (9 May 2018).

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 Oct 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28649519/4092178)

[16] Robert Montgomery Martin, The British colonies: their history, extent, condition and resources, Volume 3 (London, 1850), p.552.

[17] Sydney Chronicle, 9 Dec 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31749417?searchTerm=the%20failure%20of%20the%20potato%20crop%20in%20ireland%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=dateFrom=1846-11-01|||dateTo=1846-12-15|||sortby=dateAsc)

[18] Campbell, Irelands new worlds, p.17.

[19] Sydney Chronicle, 9 Dec 1846, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31749417?searchTerm=the%20failure%20of%20the%20potato%20crop%20in%20ireland%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=dateFrom=1846-11-01|||dateTo=1846-12-15|||sortby=dateAsc)