The focus here is on how the settlers in mid-nineteenth-century New South Wales attempted to live in a new world, and their struggles to become self-sufficient as the years passed. Becoming completely self-sufficient was of great difficulty to the incoming settlers in the harsh unforgiving lands of the Australia continent, but especially for the Irish who were generally accustomed to more fertile agricultural lands. From the very beginning of the colony’s history, it was the common goal amongst the leaders of the various regions in Australia, to be able to go from colonies which depended solely on the goodwill and assistance of the British empire, to a land which was capable of becoming as close to self-sufficient as possible. This was done through a wide variety of sectors which were each as important the other.

Horse drawn wagons carrying wool bales from the station (date unknown). Source: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences Collection, Ref: 85/1284-1628

Farming was of significant importance to the Irish settlers. Many of those who moved to Australia did so in search of a better life and relied on the land to make a decent living. One such aspect of farm life was raising sheep. Australian wool became a prime source of income for many Australian farmers, and was vital to the linen industry that supported much of the economy.[1] Another important aspect was the movement of the produce to the farms which supplied the farmers with the necessary money to continue their farming lifestyle. While some of the Irish migrants were successful in their endeavour to become completely self-sufficient, the vast majority of migrants relied on the help of others for survival in Australia. Here we grapple with the idea of the hardships that many Irish migrants dealt with both as a community and as individuals, and their struggles to become self-sufficient in the unforgiving lands of Australia.

The dream of a better life

Many Irish migrants had left their home in search of a greater quality of life in the new colonial world. Some were successful in this endeavour, including Michael Skehan, from Bridgetown in Co. Clare, who migrated to Melbourne on 1840. He later returned to Ireland in in 1853, with a wife, 5 children and £10,000 in cash, in addition to a large quantity of gold nuggets which he had acquired in his time in Australia; he purchased a farm near Scariff in Co Clare.[2] Skehan had fulfilled the dream that many Irish immigrants had. However, not all were as successful. In fact, the large majority of the Irish immigrants failed in their goals. The goldfields in Australia, and their immediate vicinities, were littered with Irish settlers who had made their way to the colonies to make their fortune; the vast majority soon gave up their lives as treasure hunters and settled down into more traditional roles, such as those that were common back in Ireland: farmers or blacksmiths.

In addition to those who had failed to find work in Australia, there were those migrants who had failed to settle, purely for the reason that they were unable to stay in a land so far from home. While the majority of Irish migrants who travelled to the new colony were poor and uneducated, some few migrants, such as Thomas Smyth, were highly educated prior to leaving Ireland, and set out to Australia in search of a new life. One would be led to believe that making a successful life in the colonies would be well within the reach of an educated and wealth young man. However, this was not always the situation, as with Smyth, who documented his disillusionment with his new life, claiming that in the colonies ‘education + gentility out here = poverty.’ Smyth was one of the few Irish migrants who returned home from Australia due to a lack of work opportunities and from home sickness, ‘the reason for my leaving was a severe illness brought upon by disappointment’.[3] However, the vast majority of Irish migrants who had moved out to Australia could not afford to return to Ireland because of something as trivial as homesickness; they needed to find ways to make it viable for them to continue living so far from the familial support that they would be used to.

An Irish success story

By the mid-1850s Australia had a large Irish population, whether Irish-born or descended from Irish parents. The town of Boorowa in New South Wales in particular had a large Irish demographic, with Irish born immigrants making up 20.6 percent of the population in the region.[4] This area of Australia had a thriving economy, which some historians attribute to the large population of hard working Irish migrants living in the area.[5] The Irish people of the nineteenth century were predominantly rural, and the same can be said for the migrants who made their way to the Australian wildlands. The numerical strength of Irish settlers in New South Wales during this period only helped to increase the influx of migrants into the region around Boorowa.

The region made it easy for the incoming settlers to access the land with little difficulty, and allowed many of the migrants to begin their new farms; however, it was not necessarily easy land to farm. The local population was also not entirely made up of Roman Catholics.[6] It included a wide range of different people, with differing skills and backgrounds. It was due to the wide range of differences, each with their own varying regional and social origins that made the region so attractive to incoming immigrants. With each of these new migrants, came new workers, each with their own set of skills and knowledge, which helped shape the structure of the local economy.

On closer examination of the rural Irish settlements around Boorowa, it can be clearly seen that the local Irish populace played a dominant role in the creation and control of the local economy, and in the establishment of a more distinct Irish ideology which had until at least the late 1860s, marginalised sectarian and national divisions.[7] It sought to create a more equal economy, and had set put to diminish the extent of the economic inequality that was common place throughout much of the continent. [8] The areas around Boorowa had an emphasis on mutual dependence and on sharing experiences together as a population, in order to survive and thrive. Haygarth had claimed that there was no area more traversable without money or friends as the bush was, and that no matter where someone was, as long as they could make it to a homestead somewhere in the bush, they would have a place to stay.[9] This highlights the necessity for mutual dependence throughout the harsh wilderness of Australia, and humanity’s need for companionship and its dislike of overbearing solitude.

The Irish immigrants who settled in the rural areas of New South Wales displayed an enthusiasm for life and the opportunities presented by the vast amounts of land available on the frontier that was not seen in many other regions. The first wave of Irish immigrants had an insatiable hunger for the land, and went to any lengths to acquire enough to become self-sufficient, no matter the distance from other groups or cities. One such success story would was that of Edward (Ned) Ryan.

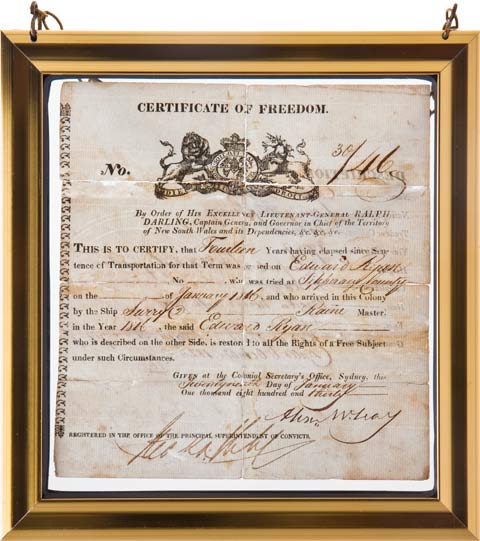

Ned Ryan’s certificate of freedom, 1830. Source: National Museum of Australia

Ryan was an ex-convict transported to Australia but granted his freedom in 1830 after serving a fourteen year sentence. Over the next decade he acquired land and came to own the largest Irish farm near Boorowa which was reputably over 100,000 square miles. However, this is widely believed to be a vast exaggeration with only, at most, 400 square miles ever accounted for.[10] Ryan fought vigorously for, and in defence of, his land, which often brought much trouble and difficulty down upon him with local newspapers accusing him of arson and physical violence against other migrants.[11]

The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, for example, reported in 1849 that these other migrants were ‘unlicensed occupiers of crown lands’ who were on the receiving end of ‘Lynch Law’ from Ned Ryan and his associates.[12] These squatters had their illegal buildings and fences burned down by dissatisfied locals. However, what this accusation demonstrates is just how far the Irish migrants were willing to go for the land they now called their home. Ryan, along with his friends and compatriots, shaped a sizable rural region in which the Irish were fully fledged participants from the outset, who did not lean on any local support, but rather were almost completely self-sufficient.

Ryan’s success was a key reason for many of the incoming Irish migrants into the area surrounding Boorowa. By the late 1850s, Ryan was such a vital member of the community that the Sydney Morning Herald claimed that he had been ‘mainly responsible in attracting the present population and still holds every inducement to men of industry and integrity to settle in his neighbourhood’.[13] Ryan was clearly eager to increase the takings of the local economy, and did so by purchasing twenty nine farms in the vicinity of Boorowa in the hopes that he would be able to increase the size of the settlement.[14] Many new settlers took advantage of Ryan’s offers, with studies showing a large numbers of migrants from Ryan’s hometown of Clounoulty in Co. Tipperary living in the new rural district pioneered by him and his fellow landlords.[15]

An unfortunate failure

While there were some success stories, such as Ryan’s, there were a much greater number of Irish migrants who were unsuccessful in creating new lives for themselves. For many, the opportunities presented by life in Australia meant a new life. A chance at rebirth. However, many migrants who had come to Australia in search of treasures and riches were unsuccessful. One such example that O’ Farrell cites is that of the Finn brothers: Michael, Patrick, John and Thomas. The brothers were quite successful in their endeavours, earning a considerable sum of money. From the outside, it seemed like a migrant success story, however, underneath the surface, one can see how this was false.

One brother, Thomas, exemplified the characteristics that many Irish migrants possessed, carrying out the fantasies that many middle income Irish migrants often dreamed of carrying out, and as a result of acting on his most ambitious dreams, went bankrupt in 1872, and had a mental breakdown. He remained mental incapable until his death in 1895.[16] Finn portrayed the negative aspect of the middle-class Irish to the most extreme measures.

Farmers harvesting asparagus. Source: State Records – Digital Gallery (NSW)

While the vast majority of Irish migrants were lower class, and thus failed due to believing they would not succeed, and only purchased land on small scales, in some cases it was, in fact, due to the migrants purchasing large portions of land of an inferior quality. Much of the reasoning behind poor Irish farmers failing can be based on the fact that their vision was too constricted, too narrow for the wide expanses of the Australian wilderness. In contrast to this, the middle and upper class Irish migrants’ key faults were the opposite of this – their visions were often too ambitious for their means, and so they often ended up destitute.

A typical problem for more ambitious migrants then was to buy massive tracts of land for the sole reason that it was cheap and they could afford it. Many of these men believed their worth was equal to the quantity of land one owned, rather than the quality of the land that they possessed. [17] Very often, these men fell into the trap of owning expansive areas of un-farmable land, living as the lord of their own inhospitable domain, with little to no chance of sustaining oneself or their family.

For many Irish people, then, the lure of a new life, filled with riches beyond their wildest imaginations was too great an opportunity to resist. Many migrants did not get to live out this fantasy, however. The lives of these migrants had become more difficult once they had moved from their ancestral home, away from the support of their families and communities.[18] However, this did not mean every single migrant lived in poverty. Some did become vital members of their communities, and shaped the social construction and the economies of their region. Whatever one may say, however, the Irish played a vital role in the creation of a viable economy in Australia through their attempts to become completely self-sufficient.

REFERENCES

[1] Rev. Henry William Haygarth, Recollections of bush life in Australia: during a residence of eight years in the interior (London, 1861) p. 43, HaithiTrust Digital Library (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433082444807)

[2] Patrick O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia: 1788 to the present (Cork,1987), p. 114.

[3] O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, p. 115.

[4] Malcolm Campbell ‘The other immigrants: comparing the Irish in Australia and the United States’, Journal of American Ethnic History, 14, 3 (1995) pp 3-22: 4.

[5] Campbell, ‘The other immigrants’, p.5.

[6] David Fitzpatrick, ‘The settlers: immigration from Ireland in the nineteenth century’ in Colm Kiernan (eds) Ireland and Australia (Sydney, 1984), p. 28.

[7] Haygarth, Recollections of bush life in Australia, p.22.

[8] Campbell, ‘The other immigrants’, p.6.

[9] Haygarth, Recollections of bush life in Australia, p.24.

[10] Campbell, ‘The other immigrants’, p.7. See also: ‘King of Galong Castle’, Not Just Ned: a true history of the Irish in Australia, National Museum of Australia (http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/irish_in_australia/exhibition_overview/story_circle)

[11] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 14 Apr. 1849, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101730563?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FG%2Ftitle%2F364%2F1849%2F04%2F14%2Fpage%2F9477056%2Farticle%2F101730563)

[12] Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 14 Apr. 1849, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101730563?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FG%2Ftitle%2F364%2F1849%2F04%2F14%2Fpage%2F9477056%2Farticle%2F101730563)

[13] ‘Wandering in the Bush’, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 Aug. 1859, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13029297?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FS%2Ftitle%2F35%2F1859%2F08%2F15%2Fpage%2F1489780%2Farticle%2F13029297#)

[14] Campbell, ‘The other immigrants’, p.9.

[15] Campbell, ‘The other immigrants’, p.10.

[16] O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, p.122.

[17] O’Farrell, The Irish in Australia, p.123.

[18] Haygarth, Recollections of bush life in Australia, p.2.