The nineteenth century marked the beginning of state-provided care for the mentally ill in the Australian colonies. This led to the first government funded mental institution in South Australia. It opened its doors in 1846. Originally named the Glenside Lunatic Asylum, it was located outside of Adelaide and could cater for sixty patients. After just two years of operation, however, it was deemed incapable of meeting the demands of the area.

From the moment of their establishment, these asylums witnessed a disproportionate number of Irish immigrants being committed over any other social group. It was believed that the lax selection process of immigrants along with the long sea journey had an adverse effect on those received into Australia. Paired with the disappointment of the immigrants once they arrived to find they had been sold an unattainable dream in regard as to the lifestyle they were likely to lead, this placed strain on the mental capacity of many. Irish immigrants suffered under the pressures of life in colonial South Australia during the nineteenth century. They found themselves in an urban environment that was alien to them and that continued to expand at a rapid pace. Their ability to integrate themselves into this economy proved too much for many which reflected in their need for medical treatment for mental illnesses. Their disappointment with colonial life and their inability to keep up with its pace led to mental breakdowns.[1] Another factor in the disproportionate appearance of Irish immigrants in institutional records can be seen in the influx of young Irish women to Adelaide from Irish orphanages and poorhouses. These women were sent away in an attempt to relieve the pressure on such institutions at home. However, a large portion of these women came from poor socio-economic backgrounds which made them prone to mental illness. They were not prepared to deal with the strain of a growing urban city such as Adelaide.

The first ‘planned’ colony

Irish immigrants destined for Australia were from a range of backgrounds; however, records indicate that a large number of them were involved in manual labour. All Irish immigrants had the commonality that they were accustomed to a rural economy. In Ireland, there was no urban area that developed at a rate that could have prepared them for what they encountered on arrival in Adelaide.

South Australia was the first colony to put Edward Gibbons Wakefield’s doctrine on how to develop a colony most efficiently into practice. It pointed out the flawed dependency on convict labour within the current settlements. Wakefield believed that Australia should be encouraging immigrants to come from Britain and Europe to take up the work necessary.

The 1834 South Australia Act reflected Edward Gibbons Wakefield’s advice on this topic.[2] The urban development of Adelaide moved at a quicker rate than other major cities in the penal colonies of Australia. Manual labour was needed in the early years of the colony but the Irish arrived in South Australia after this initial period of development. This led to an overpopulation of manual labourers which placed pressure on job availability and they found it difficult to assimilate to this newly formed society.[3]

Young Irish women fell victim to mental health issues due to a number of factors at play in Adelaide in the nineteenth century. There was a need for labour and a balance of the sexes and the solution was seen to be the recruitment of young Irish women. This took place under the Earl Grey Scheme between 1848 and 1850. Young Irish women were sent to Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide to address the demand for domestic servants and young single women suitable for marriage.[4] Two waves of Irish women arrived in Adelaide to find they were not prepared for the work available. Many of the women had been sent from orphanages and poorhouses back in Ireland. This seemed to be an ideal solution as Adelaide required young women while these institutions in Ireland needed to relive some of the burden by providing for these women placed on them.

‘The Irish females’

The South Australian Register newspaper was a radical publication during its beginnings as it was not subject to strict government controls. It revealed the sentiments of some of the people of Adelaide during this period. Although they claimed to support emigration into the area, the paper condemned the situation that had arisen in Adelaide in an 1855 article entitled ‘The Irish Females’. The piece outlined that the need in Adelaide was for young women who could occupy roles in domestic service. However, when the young Irish girls arrived it was soon discovered that they were not trained in the level of work required of them. These women were forced to live off government aid; food and shelter was provided but Adelaide citizens felt that they should give back in some way.

Adelaide, had by the 1850s, developed into a vibrant urban centre which had a social class with first class tendencies. The young Irish immigrant women had the skills to be farm servants rather than those expected of domestic servants as they were largely unfamiliar with upper class social etiquette.[5] It was suggested by the newspaper that these young women be put to work in tasks like those attributed to citizens that committed a crime. These women were dropped into a society that was unknown to them and when they struggled to find the footing they were not met with assistance from the wider population.

Due to a combination of their rural backgrounds and lack of skills, many young Irish women were severely disappointed with the life that faced them on arrival in South Australia. The urban development of South Australia provided a mixed measure of success for some Irish immigrants but in the case of these destitute women it proved detrimental to their ability to integrate into the society they found themselves in. Some were driven to take drastic measures in order to survive.

Records kept of the women that arrived on the ship, Inconstant, as part of the Earl Grey Scheme, reveals this. Sixteen of the young girls that were transported to South Australia on the Inconstant were reduced to prostitution as a means of income following their arrival in the colony. As Mark Staniforth has argued, these women faced not only a competitive working environment but also a disregard by those in positions of authority.[6] One female passenger on the Inconstant, Eliza Taafe, was declared insane on arrival in Adelaide, following allegations that the captain of the ship and the matron were involved in misconduct over the course of the long journey. However, when Eliza Taafe made such accusations she was declared ‘insane’. This was sometimes the case with the Irish as well as other groupings within society. The asylums were used as a dumping site for people who were considered trouble-makers or barriers to progress in this fast-paced developing urban society.

The difficulties of integration

Unlike other colonies in which the Irish had a large community through which they had an element of influence such as Melbourne. In Adelaide the Irish were entering an already established colony. They needed to assimilate to the urban society around them. The labour background of the Irish proved to undermine their attempts to fit into this rapidly developing society.

According to Eric Richards, the Irish were among the poorest category of immigrants in South Australia during the nineteenth century.[7] Moreover, on arrival in Australia, they were entering ‘a new and rapidly expanding British colony’.[8] There were greater opportunities to acquire land and make a fortune than at home in Ireland. However, the unpredictability of life as an Irish immigrant in a foreign, yet British, land took a toll on the mental health of some. Their status as manual labourers would have had an impact on their encounter with mental institutions as those closer to the poverty line tended to be more prone to mental illness.

Admission registers studied by Elizabeth Malcolm show that there was a higher rate of labouring Irish registered with institutions during this period than in general with thirty-six per cent of the Irish males committed having a labouring background.[9] Many were overwhelmed by the pressure to find success in this land of opportunity as it had been sold to them back in Ireland.

The provision of mental health care

It was during the nineteenth century that a focus began to be drawn to mental health care both in Europe and Australia. For the most part Australia strived to follow the path of Britain in regards the treatment of the mentally ill. In the mid-nineteenth century, the first purpose built asylum was opened in Adelaide. The best plans for the care of the mentally ill were created in South Australia but these did not come to fruition due to several factors including the financial difficulties in providing the best care along with the lack of professional knowledge of psychiatric care. Although it was unprepared for catering to the mental health needs of the area, it portrayed the changing opinion on mental health. It was no longer treating those who suffered from mental illnesses as a burden but a group within society that should be helped. [10]

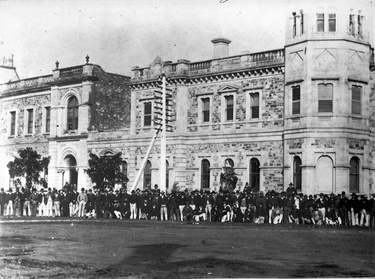

Australian asylums were built to reflect the standards of those back in Britain where buildings for each gender were separated by placing the administrative building in between the two; this was to prevent the patients from developing sexual relationships as this was deemed harmful to their treatment.[11] Irish immigrants appear disproportionately in the records for mental institutions due to a number of reasons related to the fast-paced development of Adelaide and the greater South Australian area. The development of public mental health care moved at a pace that matched the rapid growth of the city. The Irish did not arrive in large numbers during the founding years of the colony which led to difficulties when they did try to integrate themselves into the area. South Australia’s rapid urbanisation process left it open for a mixed experience of success for Irish immigrants. In regard to mental health this quick development was detrimental to their level of success.

Economic conditions in Adelaide in the nineteenth century were not favourable to the large number of Irish immigrants who found their vocation in labour work. It would appear for the most part the Irish missed the wave for manual labour in Adelaide and struggled find sufficient employment. On arrival in Adelaide many were faced with immense disappointment with the lifestyle they were dealt. This led to an increased number of mental breakdowns among young Irish men in Adelaide.[12]

Furthermore, the Earl Grey Scheme which was intended to have a positive effect in Adelaide, by providing a balance of genders to the city and fulfill the need for domestic servants, proved to be ineffective. The young Irish girls that arrived were untrained for these positions and typically came from harsh socio-economic backgrounds which played a role in their likelihood to encounter mental illness during this period. Unequipped for life in urban Adelaide, many of these women turned to unsavoury work or became reliant on the state for survival. This led to a growing anti-Irish sentiment among the wider community of Adelaide who felt that the wrong type of Irish had been selected for assisted passage.[13] This added element of segregation impacted the mental health of female Irish immigrants in Adelaide.

REFERENCES:

[1] Susan Piddock, ‘Possibilities and realities: South Australia’s asylums in the nineteenth century’ in Australasian Psychiatry, 12.2 (2004), p. 172.

[2] Transcript of ‘An act to empower his majesty to erect South Australia into a British province or Provinces and to provide for the colonization and Government thereof’, 15 August 1834, Museum of Australian Democracy, (http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/sa1_doc_1834.pdf) (29 March 2017)

[3] Eric Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’ in Irish Historical Studies, 27.107 (1991), p.217.

[4] ‘The Irish Females’ in South Australian Register, 4 July 1855, National Library of Australia’s Trove, (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/49298639?searchTerm=The%20Irish%20Females&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia|||l-title=41|||l-availability=y) (1 April 2017)

[5] Eric Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’ in Irish Historical Studies, 27.107 (1991), p. 222.

[6] Mark Staniforth, ‘The Inconstant girls: the migration experience of nearly 200 Irish orphan girls and young women sent to Adelaide in 1849 aboard the barque Inconstant’ in Sue Williams, Dymphna Loneragen, Rick Hosking, Laura Deane and Nena Bierbaum, The regenerative spirit (Adelaide, 2004), pp 27-41.

[7] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’, p. 220.

[8] Elizabeth Malcolm, ‘Irish immigrants in a colonial asylum during the Australian gold rushes, 1848-1869’ in Asylums, mental health care and the Irish, 1800-2010 (Dublin, 2017), p. 123.

[9] Malcolm, ‘Irish immigrants in a colonial asylums’, p. 131.

[10] Piddock, ‘Possibilities and realities: South Australia’s asylums’, p. 175.

[11] Susan Piddock, ‘To each a space: class, classification and gender in Colonial South Australian Institutions’ in Historical Archaeology, 45.3 (2011), p. 100.

[12] Piddock, ‘Possibilities and Realities: South Australia’s asylums’, p. 172.

[13] Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’, p. 225.