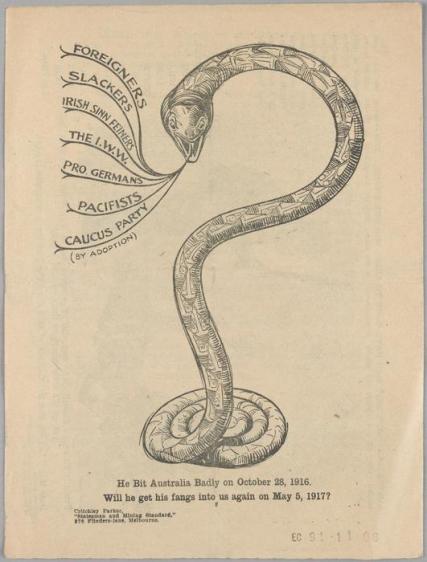

Cartoon: Irish snake. Source: Special Broadcasting Service, Australia

The effects of the so-called ‘Sinn Féin Rebellion’ in Dublin in 1916 influenced politics and society not just in Ireland but all over the world where Irish people lived in the early 1900s. The newly federated Australian Commonwealth, with a large Irish settler population, was one of these places. Sinn Féin (‘we ourselves’), the Irish republican Irish party erroneously held responsible for the 1916 Easter rising, were the dominant force in Irish politics by 1918 and tensions with representatives and authorities of the British Empire would be inevitable. This growth in tension tested and changed the lives of any Irish settlers in Australia who aligned themselves in any way with this party. Even those Irish who did not align with Sinn Féin (a byword for Irish troublemaker) were tainted by misconceived conceptions of the movement in Ireland, causing a number deportations and arrests under the Immigration act of 1901 and the War Precautions Regulations act of 1914. As well as the texts of this legislation, newspapers will provide contemporary evidence of the treatment of those associated with Sinn Féin in Australia in the early twentieth century; Michael Patrick Considine (1885–1959) was one such man.

The Considine case

Considine was an Irish union militant and politician. He was a practising catholic and a proud socialist. Originally from county Mayo in Ireland, he was just five years old when he arrived in New South Wales in September 1890. He was named after his father, also Michael Patrick, who was a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary, and was a part of the labour and industrial movements, especially within the mining community. Before his arrest in 1919 for reportedly saying publicly ‘bugger the King, he is a bloody German bastard’, he was a member of parliament; he represented the Labour Party for the Barrier constituency in the House of Representatives.[1]

Michael Patrick Considine, 191? Source: National Library Australia

Considine became well known around Australia for the charge of ‘having by word of mouth made a statement likely to cause disaffection among His Majesty’s subjects’ under the War Precautions Regulations act of 1914. This act was initiated by the Australian Parliament under the threats posed by the First World War. It gave the Australian Government to new powers; the Governor General, for instance, was able to change regulations and orders for the safety of the Commonwealth of Australia during wartime. It was under this legislation that Considine was apprehended on a charge of disloyalty in July 1919. The New Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, a working-class mining newspaper, reported that he was charged with being a ‘Sinn Féiner’, something he admitted.. George William Dawes, a returned soldier, also gave evidence, describing an argument with Considine and confirming the use of the words complained of and ‘the improper language used’ to slander King George V.[2]

The Argus, a largely Conservative newspaper from Melbourne, received a ‘letter to the editor’ following Considine’s incarceration, in which the writer questioned if Considine would continue to receive payment for his work as a parliamentarian whilst imprisoned. His slandering of the king had caused him to be incarcerated for twenty one days in Melbourne Gaol and he was ‘ordered to enter into a bond of £100 to be of good behaviour for 12 months’. It is notable that the letter writer identified as ‘NOT A SINN FÉINER’, emphasising that they were not allied to Considine or the punishable political association.[3]

A report by The Argus on Considine’s appeal against his conviction revealed that his appeal was on the ‘grounds that the decision was wrong at law and against the evidence; that evidence was wrongly admitted; that on the evidence the defendant should not have been convicted; and that there was no evidence that the defendant committed the offence.’ [4] A transcript of the appeal case indicated that Considine had been targeted as a member of Sinn Féin; his lawyers, Mr. McArthur, and Mr. A. W. Foster argued against this stating that there was no proof. Mr. Isaac Henry Cohen, a prominent politician who later was elected to the Victorian Legislative Council for Melbourne Province and King’s Counsel, was the opposition to the appeal chosen by the Commonwealth Crown Solicitor. Cohen’s lawyer argued against the appeal, assuring Judge Wolnarski that no matter what Considine had said, if it was true or false, it had been with disaffection. Cohen also suggested that Considine should have known better as he was a member of parliament. When Cohen was asked for evidence of these charges, he could not provide any proof other than the witness George Dawes who was under oath. The appeal was dismissed ultimately dismissed by the judge so Considine carried out his sentence and paid his fine.[5]

‘Would the Sinn Féiners rather be Germans?’

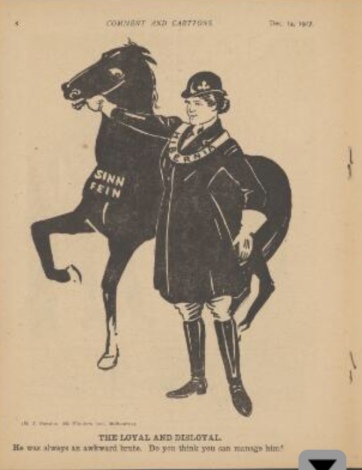

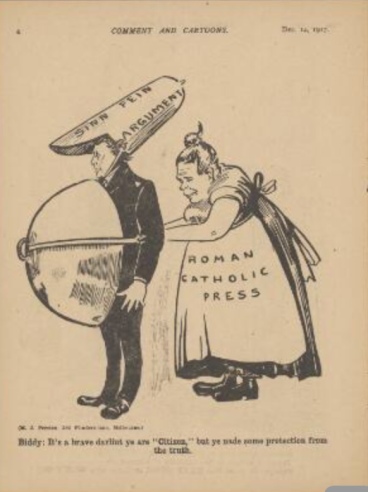

Irish immigrants who travelled to Australia during the end of the long nineteenth century were sometimes defined as ‘undesirable’. This discrimination of Irish immigrants by the early twentieth century was often because of their membership or their affiliation with the Irish political party of Sinn Féin. ‘Sinn Féiners’ began to be thought of amongst Australian officials as people disloyal to the British Empire, mainly because of the attack on the 1916 British government in Ireland while Britain was at war.[6] The War Precautions Regulations act of 1914 was established to protect Australia and the British Commonwealth following the outbreak of the First World War and was intended to defend the Commonwealth and public safety. The act provided for ‘enemy aliens’ and ‘disloyal’ subjects – Sinn Féin members came under these terms in the aftermath of the 1916 rising.[7] The party and its members were also reported to be in favour of Britain’s enemy Germany, an issue that made many newspaper headlines in Australia. In an article titled ‘The Preference for Germany’ in The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, a New South Wales newspaper that supported the British Empire, the American journalist D. Thomas Curtin pondered the question ‘Would the Sinn Féiners rather be Germans?’[8] High profile supporters like Archbishop Mannix who gave speeches all around Australia, were seen to radicalise to Irish community. In 1919, an attempt was made to introduce an Immigration Bill that would prohibit members of Sinn Féin from entering the Commonwealth of Australia.[9]

Cartoon: The Loyal and disloyal. Source: National Library Australia

In January 1901, the Federation of the Commonwealth of Australia was founded. The federation of Australia comprised of six states, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia. These states had their own constitutions and parliaments; they then gained control of legislation. This included the Immigration Restriction act of 1901, more commonly known as the ‘White Australia Policy’. The policy prevented the immigration of individuals considered to be ‘unsuitable’ because of their Asiatic or their non-European origins. An amendment to the Immigration Restriction act of 1901 in 1904 meant that prospective immigrants to Australia had to complete a dictation test. This test required prospective immigrants to write out 50 words in any European language, dictated to them by an officer in a European language.[10] The dictation test was largely unfair to non-English or other European language speakers and purposely installed a ‘racial bar’. Although there was a racial discriminatory element to the operation of the Act, officials in both Australia and Great Britain did not actually mention race specifically in the text of the act.[11]

‘girding against our flag’

Cartoon: Sinn Fein and the Roman Catholic Press. Source: National Library Australia

While the Immigration Restriction act of 1901 was established to limit the immigration into Australia, it gave Australian officials the opportunity of prohibiting all types of ‘undesirable’ migrants from entering the new country if they chose.[12] It primarily targeted Chinese immigrants who were characterised in newspaper reports prior to the Immigration Restriction act as immoral and corrupt. During a Royal Commission on Chinese gambling in 1891 in the Chinese Quarter of New South Wales, however, ‘all occupants protested their innocence of gambling or opium smoking’.[13] The act was not only to prohibit Asian immigration however but also other ‘undesirables’ from within the British Empire and so British (and Irish) subjects, for political or other reasons, were sometimes treated unfairly and given unfair dictation tests by the Australian authorities.

The Australian Government tried to hinder the development of support for Irish Republicanism in Australia but they were unsuccessful as the Sinn Féin movement in Australia continued to grow after the First World War. A key figure amongst these movements was Daniel Patrick Mannix, an Irish Bishop from county Cork. Mannix was intently interested in Irish political matters and was a vocal supporter and recruiter for the Sinn Féin and the Irish republican movements all over Australia. Mannix did this by travelling around Australia making and giving speeches at various rallies or events. He was an advocate of anti-violence in Australia. He campaigned heavily for anti-conscription and though initially not in favour the 1916 rising in Dublin, he supported Sinn Féin members’ rhetoric. There were many in the Australian Government who wished to stop Mannix – a prominent political as well as religious figure – and many who believed he should have been deported.[14] In 1919, The Register, a South Australian newspaper, discussed Irish immigration as ‘girding against our flag.’[15]

The 1901 Immigration Restriction and the 1904 War Precautions Regulations acts were used to justify the prohibited immigration of non-European migrants to Australia but they also affected British subjects included the Irish. The introduction of the dictation test became a major advantage for Australian officials who wished to keep the ‘undesirable’ immigrants out of Australia. The attack on British forces during the 1916 rebellion by Irish Republicans in Dublin were seen as ‘disloyal’ to members of the Australian Government. A large number of these British subjects were Irish and were associated with the Irish political party of Sinn Féin. Irish settlers in Australia were also sanctioned for their association with the party, such as parliamentarian Michael Patrick Considine. This was due primarily to a fear of increasing disloyalty to the British Empire. The timing of the rising, during the First World War, was already a time of great instability for the British. The heightened need for protectionism came at a cost and it was the Irish, and those who were associated with the party of Sinn Féin, who ultimately lost out.

REFERENCES

[1] Frank Farrell, ‘Considine, Michael Patrick (1885–1959)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 8 (1981), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/considine-michael-patrick-5758/text9755) (7 Apr. 2018).

[2] New Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 26 Jul. 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove

[3] The Argus, 17 Sept. 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4688116?searchTerm=Michael%20Patrick%20Considine%20AND%20%22sinn%20fein%22&searchLimits=exactPhrase=sinn+fein|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom=1917-01-01|||dateTo=1919-12-31|||sortby ) (7 Apr. 2018).

[4] The Argus, 13 Sept. 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4690605) (9 May 2018)

[5] The Sun, 13 Sept. 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/221984577?searchTerm=Michael%20Patrick%20Considine%20AND%20%22sinn%20fein%22&searchLimits=exactPhrase=sinn+fein|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom=1917-01-01|||dateTo=1919-12-31|||sortby ) (7 Apr. 2018).

[6] David Dutton, One of Us?: a century of Australian citizenship (New South Wales, 2002), p.106.

[7] War Precautions Act, 1914 and War Precautions Regulations, 1914 / Commonwealth of Australia (http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-38369983/view?partId=nla.obj-38369994#page/n0/mode/1up) (8 Apr. 2018).

[8] The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, 1 Feb. 1918, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/132532433?searchTerm=sinn%20feiner%20AND%20%22immigration%22&searchLimits=exactPhrase=immigration+|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom|||dateTo|||sortby|||l-decade=191) (5 Apr. 2018).

[9] The Daily News, 21 Aug. 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/81338414?searchTerm=sinn%20feiner%20AND%20%22immigration%22&searchLimits=exactPhrase=immigration+|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom|||dateTo|||sortby|||l-decade=191) (6 Apr. 2018).

[10] Mark Finnane, ‘Controlling the ‘alien’ in mid twentieth century Australia: the origins and fate of a policing role’ in Policing and Society, 19 (2009) pp.442-467.

[11] Kel Robertson, Jessie Hohmann and Iain Stewart, ‘Dictating to one of “us”: the migration of Mrs Freer’ in Macquarie Law Journal, 5 (2005) pp 241-3.

[12] Clarence and Richmond Examiner, 28 Jan. 1905, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/61414731?searchTerm=%22undesirable%22&searchLimits=exactPhrase=undesirable%7C%7C%7CanyWords%7C%7C%7CnotWords%7C%7C%7CrequestHandler%7C%7C%7CdateFrom=1900-01-01%7C%7C%7CdateTo=1905-12-31%7C%7C%7Csortby)( 4 Apr. 2018).

[13] Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 31 Aug. 1891, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/64229670?searchTerm=chinese&searchLimits=dateFrom=1890-01-01%7C%7C%7CdateTo=1905-12-31%7C%7C%7Cl-advstate=New+South+Wales%7C%7C%7Cl-australian=y) (7 Apr. 2018).

[14] Daily Examiner, 12 March 1918, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/195815441?searchTerm=deport%20AND%20(irish)%20AND%20%22australia%22%20AND%20%22sinn%20fein%22&searchLimits=exactPhrase=sinn+fein|||anyWords|||notWords|||requestHandler|||dateFrom=1917-01-01|||dateTo=1919-12-31|||l-state=New+South+Wales ) (6 Apr. 2018).

[15] The Register, 17 Nov. 1919, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/63119473?searchTerm=deport%20AND%20(irish)%20AND%20%22australia%22&searchLimits=dateFrom=1917-01-01|||dateTo=1919-12-31# ) (6 Apr. 2018).