Sir George Strickland Kingston (G. S. Kingston), born into affluence in Cork, Major Thomas Shuldham O’Halloran, a major-commandant and police commissioner, and Mr L-zar, an otherwise unknown Irish individual: three different backgrounds and, yet, on 1 May 1850, in South Australia, all three were found to be in the same room with nearly a hundred other Irish individuals. They were celebrating the first annual dinner of the St Patrick’s Society.[1] Founded in 1849, this Society aimed to help integrate new emigrants into the colony through providing knowledge and funding.[2] The three aforementioned individuals were prominent members with G. S. Kingston as vice-president, Major O’Halloran as president, and Mr L-zar an ordinary member that was requested to sing at the dinner by O’Halloran.

Photograph, c.1880, of Freemason’s Tavern, Pirie Street, Adelaide, where St Patrick’s Society meetings were held. Source: State Library of South Australia

The socio-economic diversity present within St. Patrick’s Society is consequently a portrayal of the multiplicity nature of South Australia’s free Irish settlers as it was created within the first decade of establishment and included majority of the emigrants. St Patrick’s Society is hence a useful starting point to explore the variety of Irish free settlers within South Australia, a window into their lives and experiences through the news publications of announcements made and issues discussed during the meetings. The Irish in South Australia challenge stereotypes imposed by the British and Scottish while simultaneously disputing the homogenous categorisation of the Irish free settlers in the historiography.

South Australia is a unique case as it was only established in 1834,[3] long after the first colony, New South Wales, was first founded in 1788.[4] In addition, it was the first colony to undergo systematic colonisation, which implied few or no transported convicts. This changed the dynamics of the relationships between different groups of settlers in South Australia, as convicts, who were deemed to be the lowest class, did not exist or function in the ways that they did elsewhere. Irish free settlers in the colony are of particular interest as the majority were not among the pioneers that aided in the founding, settling and building of the colony – again, unlike the other Australian colonies. Additionally, by the time the Irish started arriving and settling, South Australia had already a sizeable amount of British and Scottish settlers.[5] Hence, the Irish would have been subject to some deep-rooted discrimination, due to a lack of prior interaction. This could be seen during the first decade after establishment where there was, on the part of the colonial authorities, a preference for British and Scottish emigrants over the Irish. The Adelaide Observer reported that it was stated at the first St Patrick’s Society annual dinner meeting in 1849, that the ratio of British and Irish entering South Australia was twenty British to one Irish.[6]

When Major O’Halloran and G. S. Kingston reportedly wrote a petition to the governor for more checks and balances to be implemented and stop corruption at the borders, they were met with an acknowledgement that discrimination occurs and yet this was normal and hence should accept the situation. Such blatant discrimination that began from the borders of England would henceforth imply that within the colony the same attitudes existed. This preclusion of the Irish from entering the colony shows the way that the British colonial authorities generally viewed them. However, it should be noted that this discrimination was not draconian. Many members of St Patrick’s Society occupied top places in the ruling system not just in their own community but overall in South Australian social life and politics, as evidenced by the lives of Kingston and O’Halloran.

George Strickland Kingston (1807-1880)

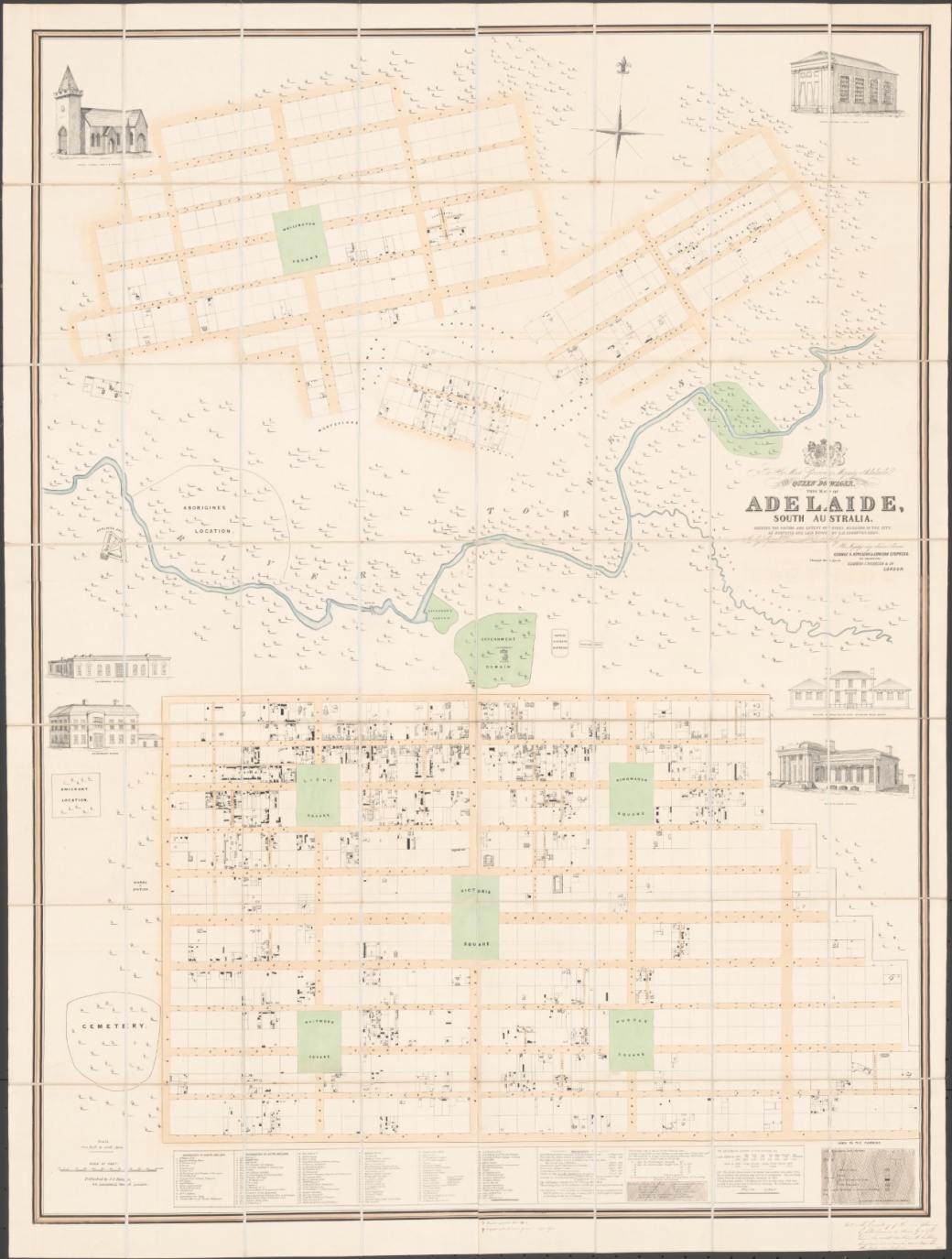

Map of Adelaide presented to the Gracious Majesty Adelaide, Queen Dowager, drawn by Sir George Strickland Kingston, 1842.

Source: National Museum of Australia,Trove

Kingston, originally from Co. Cork, Ireland, was one of the colony’s pioneers, invited to survey the land of South Australia when it was first established. A map that he drew was subsequently presented as a gift to Adelaide, the Queen Dowager. Kingston also occupied the prominent political post of Speaker of the House of the Assembly; he was a shareholder in Burra mine, and Honorary Secretary of the South Australian Adelaide Rifles Association. Even after he retired, he continued working as an architect, civil engineer and the inspector of the houses. On top of that, he contributed to the recording of the rainfall of Adelaide, forming and crafting the idea of South Australia as an advanced colony.[7]

It was said that Kingston’s life was ‘comparable to the history of the colony.’[8] The number of high positions that Kingston occupied contradicts the notion that the Irish were discriminated wholesale and had no opportunity to improve. In addition, the posts he occupied allowed for a massive personal influence and contribution to the development of South Australia. However, Kingston was most likely able to enter into these ranks because of his affluent background which gave him the opportunity to migrate to England and from there was able to participate in the political aspects of the colony down under.[9]

Thomas Shuldham O’Halloran (1797-1870)

Thomas Shuldham O’Halloran, unknown photographer, c.1865. Source: State Library of South Australia

O’Halloran is another key major figure that challenges the idea that the Irish free settlers were discriminated on the basis of stereotypes and destined to function at the bottom levels of society.[10] Contemporary images of O’Halloran did not suggest a peasant or a poverty-stricken Irishman escaping the ravages of the Great Famine; in fact, he looked wealthy and was dressed as befitted a person of a high social status. Born in India to an Irish father from Co. Limerick, O’Halloran was educated at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and went on to have a significant military in India. As an ex-captain of multiple regimes there, he was subsequently conferred the status of being the first Police Commissioner and first Police Magistrate of South Australia. He was subsequently nominated as a Justice of the Peace and as a member of the Old Legislative Council.[11] The fact that O’Halloran was recommended into these positions indicates that the Irish were not always discriminated against, especially if they were helpful; on the contrary, they held prominent positions of power and were influential in the advancement of the colony.

The Irish free settlers’ experience is thus more complex than assumed. Many historians continue to characterise Irish as having a strong bond to the family and their community,[12] as seen from the rapid use of the chain migration policy after its implementation.[13] In addition, the purpose of setting up the St Patrick’s Society was to help new emigrants speed up the process of integration.

St Patrick’s Society

At the time of its foundation, newspapers like the South Australian Gazette and Mining Journal reported an ‘Address by the Members of the St. Patrick’s Society of South Australia, to their countrymen at home’. Point 16 of the address mentioned the assisted passage schemes and appealed to landlords in Ireland to fund the passages of the cottiers and peasants.

‘A few Words to landed Proprietors. — We would take this opportunity of addressing a few words to Irish landed proprietors, confident that they will aid us in our endeavours to remove our able-bodied fellow-countrymen from a position where they are denied the means of earning a bare subsistence of the poorest fare, to one where not only an abundant supply of wholesome food may be obtained in return for their labor, but where a course of steady industry for a short period will ensure them an independence.’ [14]

The focus here was on ‘able-bodied fellow-countrymen’ rather than looking to encourage the emigration of as many people as possible – including females, children and the elderly who might be afforded the option of fleeing the ravages of the Great Famine which was had been devastating the rural poor since 1845. It reveals a variation in the attitudes of Irish free settlers towards other potential settlers. The free settlers had created a group meant for the easier integration of emigrants and yet within the group, they too wanted a specific group of people that will fit their needs. This was a form of discrimination that reveals the intricacy of the Irish free settlers’ experience – they were not just victims of the prejudices of British authorities but also the perpetrators of discrimination against Irish of lower socio-economic status or towards those of most ‘use’ at any given time. This also provides a glimpse into the ways that the successful Irish may have wanted to portray themselves towards the rest of society.

One documented stereotype that some British people had was that the Irish were lazy and had a lack of responsibility towards the community, something the respectable Irish in South Australia tried to counter under the aegis of St Patrick’s Society.[15] The society’s committee reported to the General Meeting of the Members on 1 May 1850:

‘Your Committee have caused blank forms to be printed and distributed, in the hope that the Irishmen resident in the colony would enable them, by the exhibition of authentic documents, to prove to the world that the Irish emigrants are amongst the most orderly and thrifty of the labouring population of this province; but they regret that front some unaccountable misconception very few of these forms have been returned filled up; and they would urge your influence in your several neighbourhoods to induce the proper filling up and authentication of these returns.’ [16]

This action by the St Patrick’s Society evidences the idea some Irish wanted to promote themselves as more organised, and as the ideal citizens that the colony wanted and needed.

South Australia’s St Patrick’s Society did not escape criticism, censure and ridicule. Around the time of its society’s foundation in 1849, a letter penned by somebody using the pseudonym ‘Blue Nose’ and published in the South Australian Register, was scathing in its criticism of this ‘Irish club’. It also criticised the information it was disseminating about the need for workers in the colony: What must the thinking public argue from your exhibition of pious zeal, and disinterested devotion to the welfare of your fellow-countrymen, by your exertions to overflow the already glutted labour market by such unwarrantable misrepresentations?’[17] It went on to condemn the society’s practice of society distributing forms for every member to ‘fill up, sign, and expose his circumstances in minute detail’ sarcastically proclaiming: ‘What a beautiful system of prying into other people’s affairs!’ [18]

The category ‘Irish free settlers’ is one that should be treated with caution. As seen through the experiences of Kingston, O’Halloran and other Irish free settlers individuals had differing levels of influence within the Irish community as well as the broader South Australian colonial community and were also not constantly subjected to discrimination. The Irish were more than just a group of free emigrants that settled in South Australia; they were individuals with different social status and hence different level of direct or indirect influence on South Australia’s development. In addition, they had varying views about the ways that they should portray themselves to the rest of society. It is crucial then to remember that the Irish free settlers’ experience was complex and heterogeneous, contingent on the opportunities and horizons offered by individual origins and circumstances.

REFERENCES

[1] South Australian Register, 3 May 1850. National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/38434625?searchTerm=st%20patrick%27s%20society%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia|||l-category=Article|||l-decade=185)

[2] ‘St Patrick’s Society of South Australia,’ South Australian Gazette and Mining Journal. 28 July 1849. National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/195938144?searchTerm=st%20patrick%27s%20society%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia|||l-decade=184 )

[3] Susan Arthure, ‘Being Irish: The nineteenth-century South Australian community of Baker’s Flat’ in Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress, 115 (2015), pp 169-188: 172.

[4] ‘Emigration To Australia, New Zealand And South Africa’ information sheet last revised 2016, at Museum of Liverpool: Maritimes Archive and Library (https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/maritime/archive/sheet/12)

[5] Arthure, ‘Being Irish: The nineteenth-century South Australian community of Baker’s Flat’, pp 169-188: 172.

[6] ‘Saint Patrick’s Society of South Australia,’ Adelaide Observer, 14 Jul 1849. National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/18836007?searchTerm=st%20patrick%27s%20society%20south%20australia%201849&searchLimits= )

[7] ‘Death Of Sir George Kingston,’ The South Australian Advertiser, 11 Dec 1880, National Library of Australia’s Trove https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/30809704?searchTerm=george%20strickland%20kingston%20death%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=

[8] ‘Death Of Sir George Strickland Kingston Kt’, Port Augusta Dispatch and Flinders’ Advertiser, 10 Dec 1880. National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/195905607?searchTerm=death%20of%20george%20strickland%20kingston%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia)

[9] Jean Prest, ‘Kingston, Sir George Strickland (1807-1880),’ 1967, Australian Dictionary of Biography National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/kingston-sir-george-strickland-2311) (20 Apr. 2018).

[10] D. Bruce Ross, ‘O’Halloran, Thomas Shuldham (1797–1870)’, 1967, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/ohalloran-thomas-shuldham-2523/text3417) (5 May 2018).

[11] ‘Death Of Major O’Halloran’, Evening Journal, 17 Aug 1870, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/196733382?searchTerm=death%20of%20major%20o%27halloran%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits= )

[12] Philip Harling, ‘Assisted emigration and the moral dilemmas of the mid-Victorian imperial state,’ in The Historical Journal, 59:4 (2016), pp 1027-1049: 1029.

[13] Susa Pruul, ‘The Irish in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia, 1788-1880,’ unpublished MA thesis, University of Adelaide, 1974.p. 195, Adelaide Research & Scholarship (AR&S), University of Adelaide (https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/103690)

[14]‘St. Patrick’s Society of South Australia’, South Australian Gazette and Mining Journal, 28 July 1849. National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/195938144?searchTerm=st%20patrick%27s%20society%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia|||l-decade=184)

[15] Arthure, ‘Being Irish: The nineteenth-century South Australian community of Baker’s Flat’, pp 169-188: 172

[16] ‘Saint Patrick’s Society,’ South Australian Gazette and Mining Journal, 2 May 1850, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/195939879?searchTerm=st%20patrick%27s%20society%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia|||l-decade=185)

[17] ‘St Patrick’s Society,’ South Australian Register, 25 Jul 1849, National Library of Australia’s Trove https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/50248024?searchTerm=st%20Patrick%27s%20society%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=South+Australia|||l-decade=184

[18] Ibid