Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne (centre) led the Australian Catholic community for fifty years. Source: Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House

From January 1788, New South Wales served the purpose of establishing a strong trade route for Britain, whose officials sought to expand the commonwealth of England. The mother country had recently lost her hold on the American colonies and Arthur Phillip, founder and governor of New South Wales, promised to restore England’s superiority. The First Fleet, led by Phillip, carried 1,500 people, many who were convicts. The Second Fleet arrived two years later allowing the colony to thrive with 4,000 people inhabiting the land by 1792.[1] The barren land was foreign to the newcomers, but the dreams of the empire of raising a new civilisation lived on within the British who arrived. According to the English settlers, New South Wales was seen as a ‘new America’, as its potential for wealth and commerce gave way to imperialistic motives. The British took the settlement and transformed it into a convict colony, as they believed that the British way of life would continue on in this antipodean world.[2]

However, it was often problematic, not least after 400 Irish arrived in 1800, many being the rebellious convicts of the 1798 rebellion in Ireland.[3] This proved to be an issue for those who sought to maintain an ‘English’ colony, forcing the Irish to take a backseat. The political convicts (not all of whom were Catholic) sent to Australia as punishment had faced unfair laws in Ireland that prevented them from owning land and taking public offices, and suffered due to poverty and famine. Many were forced to live under similar conditions in the new Australian colonies, being prevented from owning land, voting, holding office and establishing schools and churches of their own confessions.

Some of those who came from Ireland, became business men and practicing Catholics despite not being favoured by the English settlers. The Irish were, however, able to overcome the struggles they faced and established themselves as strong members of the colonies in which they resided. The colonial administrations in South Australia and New South Wales also took part in discriminatory acts, yet their histories reveal the successes of the Irish. The discrimination against the Irish, particularly Catholics, and especially in New South Wales, manifested itself within official policies regarding education and immigration. In most cases, policies gained support under the veil that Catholicism was evil and the Irish barbaric.

Government emigration: ‘No Irish need apply’

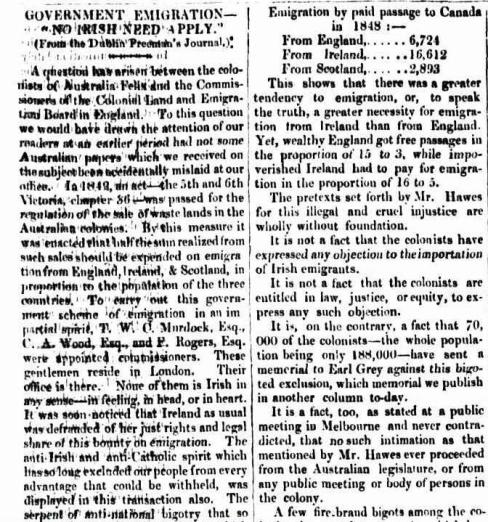

Among the types of discrimination discussed in contemporary printed sources were those centred on issues of selective migration – allowing certain groups of people to immigrate to colonial Australia – including discrepancies in travel assistance payments made by the government. In 1850, these issues were reported on by a Tasmanian newspaper, the Hobarton Guardian (reprinting information from Dublin’s Freeman’s Journal).[4] The article reminded its readers of the 1842 act that allowed the sale of wastelands, the proceeds of which would fund the passages for migrants. It had been decided that these lands would be sold in proportion to the populations of English, Scottish and Irish settlers in the colony. However, as the newspaper pointed out, the Commissioners in charge of the distribution of land did not appear to be acting fairly in this endeavour, adding ‘none of them is Irish in any sense – in feeling, in head, or in heart’.

Hobart Guardian, or True Friend of Tasmania, 14 Sep. 1850. Source: Trove

In fact, the article claimed that the Irish were being defrauded of their rights and share of monies available for passage. An ‘anti-Irish and anti-Catholic spirit’ was prevalent in the implementation of the relevant act, as the lands were sold disproportionately, disallowing Irish access to land – just as had occurred back in Ireland. The article displays an obviously bias tone but hits on many of the issues concerning the Irish at home. It claimed that thousands of able-bodied Irish labourers had been driven from their homelands by the greedy landowners and were now facing similar mistreatment in Australia.

The discrimination outlined in the article did not stop there. It pointed out that the voyage abroad proved to also be a disadvantage to the Irish as they were death-sentences to those who were forced to travel across the ocean for a ‘new hope’. Young, strong men were forced to board ships that were ‘sea hearses’ – and some buried in ‘ocean graves’ – only to land in a colony where the discrimination did not lessen. The inequality apparently did not stop there. In fact, the numbers of English arriving and Scottish and Irish arriving were drastically different. The number of English reported for New South Wales for the previous three years was over 16,600, yet the Irish and Scottish arriving equated to approximately 3,000 people each. It was reported by the same newspaper that this discrepancy was perpetuated by the British Commissioners, and that for every Irish immigrant, five English immigrants received free passage, however for every five Englishmen, sixteen Irishmen had to pay for their expenses.

The historian David Fitzpatrick claims in his Oceans of Consolation: personal accounts of Irish migration to Australia that the number of Irish immigrants amounted to more than 6,000 people at this time, seventy percent of them being Catholic.[5] On first sight, this might suggest that the Hobarton Guardian newspaper in Hobart, Tasmania, (and the Freeman’s Journal in Dublin) was only reporting half of the immigrants actually arriving in Australia, possibly due to miscommunication and misinformation. But the numbers given in the newspaper concerned those who obtained free passage; it did not take into account non-government forms of assisted emigration – meaning money raised through campaigning and fundraising in Ireland.

The article also quotes from a House of Commons discussion on the issue which questioned if any intimation had been made to colonial officers not to send out Irish emigrants. Mr Hawes, the Under Secretary to the Colonies claimed for the Australian colonists the right to make such intimation if they pleased. This claim was vehemently denied by the colonists, according to the newspaper. The authorities in Britain and Ireland were also not preventing the Irish from emigrating – rather thousands were immigrating, meaning that discrimination in this line did not exist. However, most of the non-government money for passage was paid by Irishmen, many of them Catholic, while most Protestants from Scotland and England enjoyed free passage.[6]

‘[The Irish] hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our sustained courage, our decorous liberty, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry.’

– Benjamin Disraeli, 1836 [7]

Suffrage

One of the many reasons used to prohibit the Irish and other minorities from voting was if it could be said that they were not ‘sound’ of mind. The idea of being ‘sound-minded’ in order to vote was one of the items included in an 1884 resolution of South Australia. Voting rules, reported in the Daily Telegraph, outlined that all males above the age of 21, residing in the colony for at least six months, could vote.[8] Other stipulations included not being convicted of a crime and not being paid government aid. The question of who determined who had a ‘sound mind’ could facilitate discrimination against the Irish, who were typically blamed for corruption and disruption in Parliament. Some Irish Catholics were considered troublemakers, and the impoverished led astray, giving English officials, possibly ludicrous reasons, to prevent them from voting.

The Irish ‘convict’ label enabled colonial officials to exclude them from voting. Source: Irish Times

Anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment continued to spread throughout the colonies as new acts were put in place to keep the Irish from practising and teaching Catholicism in schools or any other public location. An 1859 article from the Freeman’s Journal (Sydney) expressed similar views, stating that the Catholics were weak and demure creatures.[9] Throughout the article, there seemed to be an undertone of fear that the Catholics had no regard for non-Catholics and would destroy the Protestant majority within the colonies. In fact, the fear was evident in that three priests, sent to New South Wales on the convict ships after the 1798 rebellion, were sent away within a decade of landing. Famously, Father Dixon was permitted to practice Catholicism but was soon discouraged from doing so, meaning that access to mass and sacraments was limited. Another article from the Fitzroy City Press stoked the fire as late as 1912, stating that Catholics could only be expunged of their ignorance if they became good Christians by learning Protestant ways.[10] This was the only way that these Irish men and women could be useful to their country.

Among the anti-Catholic incidents studied by Eric Richards was the arrival of the first Catholic priest in South Australia, William Benson, who did not arrive until the 1840s. Benson stated in 1843 that ‘no Catholic gentlemen of property could join the founders’ and that Irish participation in government was limited. It was only when the population of the colony reached 14,000 people that more Irish were allowed into the colony. The Catholics were generally a poor minority and were met with opposition for the rest of the century. In the 1860s, 40,000 pamphlets claiming Roman Catholicism to be rooted in evil, trying to turn most the colonists against the Irish.[11]

Education

The hatred towards Catholics extended into educational matters, with Protestants opposing the rise in Catholic institutions. It became an increasingly difficult situation as Catholic families wished to send their sons to receive a ‘liberal education’, but were forced to send their children to Protestant schools. The aforementioned Freeman’s Journal article decried the Protestant monopoly of education, complaining that most of the schools in New South Wales were run by Protestants, therefore, the allocation of educational funds was maintained by those people as well, suggesting some may have contributed to discrimination against Irish school children. The issue was that only two Catholic institutions, Lyndhurst and St. Mary’s were available, but they were not of the quality that many wanted. This did change over time, however, as an Daily Telegraph article written thirty years later claimed that the secondary schools were now mostly run by Catholics. [12]

The Irish in New South Wales fared well in comparison to their counter parts in the Caribbean. As described in Micheál Ó Siochrú’s work, the Irish transported to the Caribbean Islands faced kidnapping, servitude with little pay and a poor diet, while children were also torn away from their families and sent to Jamaica.[13] The Irish in colonial Australia, however, could gain a foothold within society despite the barriers presented to them. Irish lawyers could rise in the ranks of government and put forth legislation and be involved in cases that would undermine the British supremacy in the Australian colonies. Some were compelled to drop their association with Catholicism to acquire land and education, but re-established their faith once they arrived. Among these was the Dublin-born George Higinbotham (1826-92), chief justice of Victoria, who advocated for voting rights for men, separation of Church and state, state aid for religious institutions, and reform of land allocations.[14]

Despite being met with opposition, the Irish were able to fight back against the unfair Anglican establishment in colonial Australia, particularly in New South Wales. In the early education systems, Protestants were in control as Catholic schools were limited. The Catholic question arose as settlers set out to create a demeaning and almost monstrous image of the Irish, noting the problems caused by the outsiders. Despite legalities, Irish men were able to gain the right to vote and rise in the ranks in order to push laws and acts to benefit Catholics and even others. Irish lawyers and priests established more schools, churches and laws that allowed the freedom to practice any religion and served to undermine English hegemony and authority. The Irish soon became more equal and, perhaps, more likely to be discriminatory towards ‘new’ immigrants.

REFERENCES

[1] Alan Frost, Arthur Phillip, 1738-1814: his voyaging (Melbourne 1987), p. 320.

[2] Alan Frost, ‘”As it were another America” English ideas of the first settlement in New South Wales at the end of the eighteenth century’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 7:3 (1974), p. 256.

[3] Anne-Marie Whitaker. ‘Swords to ploughshares? The 1798 Irish rebels in New South Wales,’ in Labour History, no. 75 (1998), p. 9

[4] Hobart Guardian, or True Friend of Tasmania, 14 Sep. 1850, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/173058025?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FH%2Ftitle%2F864%2F1850%2F09%2F14%2Fpage%2F20203159%2Farticle%2F173058025) (28 Apr. 2017)

[5] David Fitzpatrick, Oceans of consolation: personal accounts of Irish migration to Australia (Ithaca, N.Y. 1994), p.13.

[6] Hobart Guardian, 14 Sep. 1850

[7] Robert Blake, Disraeli (London, 1960), pp 152–53.

[8] Daily Telegraph (Tasmania), 18 Aug. 1884, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/149513028?searchTerm=Male%20Suffrage%20Victoria&searchLimits=l-australian=y) (28 Apr. 2017)

[9] Freeman’s Journal (Sydney), 26 Mar. 1859, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/115559132?searchTerm=Protestant%20education%20in%20Australia&searchLimits=l-australian=y) (28 Apr. 2017)

[10] Fitzroy City Press (Victoria), 22 June 1912, National Library of Australia’s Trove, (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/65680393?searchTerm=Catholic%20Clergy%201820&searchLimits=l-australian=y) (28 Apr. 2017)

[11] Eric Richards, ‘Irish life and progress in colonial South Australia’, Irish Historical Studies, 27:107 (May 1991), pp 216-236.

[12] Daily Telegraph (Tasmania), 4 July 1889, National Library of Australia’s Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/150330058?searchTerm=Irish%20vote%20Australia&searchLimits=l-australian=y) (28 Apr. 2017)

[13] Micheál Ó Siochrú, “‘Shipped for the Barbadoes”: Cromwell and Irish migration to the Caribbean,’, History Ireland, 16: 4 (2008), p. 23.

[14] Ann Daniel, ‘Undermining British Australia: Irish Lawyers and the transformation of English law in Australia’, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 84: 333 (Spring 1995), pp 61-70.