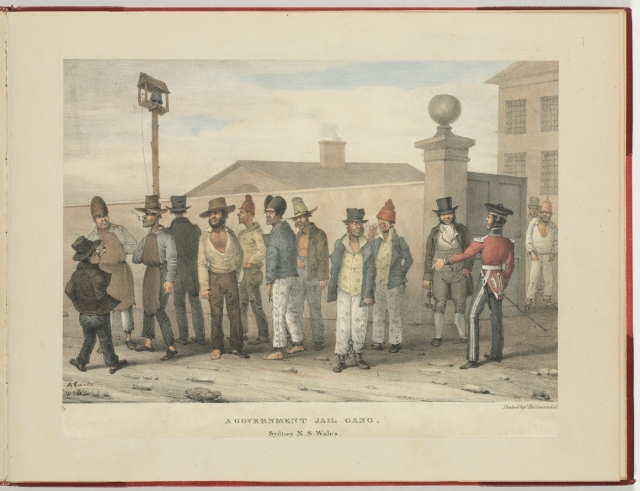

Government jail gang, Sydney, 1830. Source: State Library, New South Wales

The focus here is on the religion of the Irish convicts, demonstrating that, although in completely different circumstances, the oppression of Roman Catholicism was experienced by the Irish half-way around the world from Ireland. This will be explored through the examination of the views on differing historians on the subject, as well as analysis of relevant material from the time. Before analysing Catholicism in Australia, the subject will be discussed in relation to Ireland.

‘The usage I have seen men receive exceeds in cruelty any thing that can be credited … In particular, one poor man named Michael Cox from the County of Cork; he was compelled to walk about and work with a chain, weighing twelve pounds, on his leg, while labouring … He soon become too weak to work … Cox died a few days later’

– Joseph Holt [1]

Catholic suppression in Ireland

Before one can gain a true understanding of the oppression experienced by the first Irish Catholics to arrive in Australia, it is necessary to gain an understanding into the Catholic experience back in Ireland. Acknowledging what was happening in Ireland gives a better grounding when trying to understand the events that took place in Australia with regards to the mistreatment of Irish Catholic convicts. (For clarity, hereafter references to Irish convicts refers to those that are Catholic.)

During the time of transportation of convicts from Britain, penal laws were in place in Ireland. An interesting piece of literature one could read on penal laws comes from the seventeenth century in a letter published in 1687 by William Penn (1644-1718). Penn, an English Quaker who founded the province of Pennsylvania in America, had travelled to Ireland in 1669/70. He later wrote how penal legislation was not protecting Britain but harming her because he suppression of Catholicism was merely inspiring rebellious acts, rather than quelling them.[2] Historians such as Rafferty and Kelly note that it was widely regarded by the Catholic community in Ireland that the penal laws were enacted in an attempt to destroy their religion.[3] Rafferty asserts that due to the penal laws that ‘a community and a church becomes alienated from its own place, its own land, its own environment.[4] Rafferty’s comments regarding the lack of a sense of place in their own country are quite interesting, supporting Kelly’s belief that the penal laws were believed to be attempting to destroy a religion. The fact that this was the beliefs of the Irish in their home country, one would be inclined to believe that this may even become worse for an Irish Catholic on the other side of the world, especially when that person was deemed to be a law breaker, anyway.

Crime and punishment

To gain a true reflection of the way in which Irish Catholic convicts were treated, it is important to also have an understanding of their British counterpart. The fact that these men and women were in fact convicts, one would expect that none of them would be treated particularly well. A way in which one can try and gauge the treatment of each sets of convicts is to try and examine the type of convict that was sent over from Britain and Ireland. Statistically, there were far more British convicts transported to Australia than there were Irish. Shaw suggests that this was due to the fact that ‘‘ordinary’ crime was less common in Ireland than in Great Britain’.[5] Whilst this statement, albeit quite general, may in fact be correct, when one delves deeper into the trial process of the convicts from Britain and Ireland, discrepancies in how fair each convicted was treated can most definitely be found. Whilst attempting to find examples of British convicts transported to Australia without trial came to no avail, the same cannot be said about the Irish convicts. Cases like those of Father O’Neill and John Temple, demonstrate that both were convicted and transported without proper trial. Despite John Temple’s wife attempting to petition for his freedom, he was shipped out before her letter could reach Dublin Castle[6]. Many of those convicted without a proper trial would have been rebels that had negotiated to be transported, rather than executed or left to die in prison. However, many more men were transported without trial and without negotiating any sort of negotiations.[7]

Although this treatment of the Irish Catholic convicts may seem harsh, it is not entirely surprising given the extremities of the penal laws which were enforced upon them. However, this mistreatment can most definitely be seen as harsh in comparison to their other British counterparts, with it being stated by Alan Shaw that ‘only the unfit were left behind … and it was repeatedly argued that ‘immediate removal’ was an effective deterrent to crime and outrage in the country’.[8] This ruthless mistreatment of the Irish convicts was not the same in Britain, with Shaw, again, highlighting the number of British convicts that were sentenced to transportation that were actually transported, with the percentages being as low as thirty per cent during the period 1811 to 1817.[9] Whilst such percentages did fluctuate, with the numbers rising drastically at times, whilst also falling late on, when one compares this to the seemingly ruthless treatment of Irish convicts, it would be difficult to say that both sets of convicts were treated equally.

Rebel Catholics?

The belief that the majority of Irish convicts were rebels spurred tensions on even further. As Patrick O’Farrell has made clear, only about one fifth of those convicts transported from Ireland could have been described as nationalists or social rebels.[10] A common misconception seems to be that the majority of those transported from Ireland were rebels, with this almost guaranteeing to have those in Australia on edge of their potential actions. The master of the convict ship, the Anne, following a sort of mutiny, claimed that most ‘were guilty of no crimes, but were charged with political crimes into which they had been led unwittingly by secret societies’.[11] These quotes followed a so-called mutiny aboard the Anne, where the ship’s mate struck and killed a convict because of him spilling something aboard the ship. The convicts saw this as a gross injustice and decided to revolt, but the official account of events states that the convicts attempted to seize the ship and the ship’s officers were acquitted.[12] These events, as described by Costello differ massively from the perception at the time. Following the execution of Phillip Cunningham, it was told that he played a role in the mutiny on the ship and was shown leniency following this.[13] The fact that this article was published following his execution would lead one to believe that there could have been major bias against Cunningham, with the events described by Costello showing a vicious mistreatment of Irish convicts.

This can be seen again in a letter from the Governor of New South Wales, Phillip Gidley King, back to London, with him damning the actions of Irish convicts, referencing Father O’Neill as a Catholic priest ‘of the most notorious, seditious and rebellious principles’.[14] These statements by Governor King, demonstrate an exaggerated stereotype against Father O’Neill, which extended to the other Irish convicts of which he was speaking. This is an instance where one can easily derive that the Irish convicts were not treated fairly; if the Governor spoke and treated them in such a way, then it would lead one to believe that those beneath the Governor would act in the same manner towards the Irish convicts. Although relations between the Governor and the convict priests did strengthen, it is at this stage when it is best to accurately gauge if they Catholic convict community was treated fairly. It is taken that in times of trouble, it is extremely likely that they would have been mistreated, however in times when there was little friction it would give the most accuracy as to how they were treated.

Memorial to Fr. James Dixon, the first priest to say Catholic Mass in Australian history. Source: Wild Geese Heritage Museum and Library

Convict priests celebrating mass

One way that it can be demonstrated that the Catholic community was mistreated is in examining the strict regulations placed upon Father James Dixon when he was granted permission to deliver Mass. Whilst one may believe that it was in fact quite fair of the Governor to grant this permission, when one examines the strictness of the regulations, coupled with the fact that the original suppression of their religion was wholly unfair, it becomes clear that the mistreatment of Irish Catholic convicts was rife.

An article in the Sydney Gazette from 1803 outlines the regulations: mass could only be said once every three weeks; the priest in question was to be responsible for his congregations’ actions even after mass was finished; police would be present in the area where the mass is being said.[15] When one looks further into the publications of the time, it is interesting to see that on the same day (24 April 1803), in the very same publication, one can see a proclamation from the Governor, once again reminding readers of the regulations, as well as stating that Father Dixon has taken the ‘Oaths of Allegiance, Abjuration and Declaration, prescribed by Law’.[16] The simple fact that it was published twice, on the same day, really gives one the sense that although the Catholics were being granted this, they truly were walking on a strict tightrope of British regulations. The mass itself was a success at first; however this was scuppered by the Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804.

The Castle Hill Rebellion was a convict rebellion which, according to the Sydney Gazette, was dealt with quite easily. An article published on 11 March 1804, titled ‘Insurrection’, outlines the events of the rebellion, with it seeming to have caused a quite a deal of panic; however with no real damages done to the territory.[17] The piece does not offer any real insight into the actions of the rebels, or those in charge for that matter. However, once again, on the same day a similar ‘Proclamation’ was printed. The proclamation from the Governor was an ominous one, declaring that any person that ‘does not give himself or themselves up within twenty four hours, will be tried by a Court Martial, and suffer a sentence passed him or them’.[18] Although the rebellion was clearly a very serious matter, one cannot feel that the reaction from the Governor was overstated, given how well things had been going since Father Dixon was granted permission to say Mass. The Mass had originally been so well received that Father Dixon had been offered a salary of sixty pounds per annum, however following the rebellion he was held accountable for the rebel’s actions, ignoring the fact that he publicly tried to put a halt to their rebellion. Along with this Father Dixon was forced to attend the floggings and hangings of those involved, which was said to have caused him to faint at one stage.[19]

These actions would not suggest that the Governor actually considered what Father Dixon was doing to have any meaning; however it was a means of keeping the Irish convicts that he detested behaved. Overall, it is quite clear that the Irish Catholic convicts were mistreated beyond what one may consider to have been normal; this mistreatment transcended from the way in which the Catholic community back in Ireland were treated. Historians such as Patrick O’Farrell and Con Costello made it quite explicit that those in power did not favour the Catholic convicts, while Alan Shaw, whilst not entirely favouring the Irish convicts himself, offered more evidence of their mistreatment, in comparison to their British counterparts. All of their writings, along with contemporary newspaper commentaries make it clear that the Irish Catholic convict experience was one of mistreatment.

REFERENCES:

[1] Con Costello, Botany Bay: the story of the convicts transported from Ireland to Australia, 1791-1853, (Cork, 1987), p. 53.

[2] William Penn, A letter from a gentleman in the country, to his friends in London, upon the subject of the penal laws and tests (Harvard University, 1687), (http://eebo.chadwyck.com/search/full_rec?SOURCE=pgimages.cfg&ACTION=ByID&ID=99829832&FILE=&SEARCHSCREEN=param(SEARCHSCREEN)&VID=34277&PAGENO=2&ZOOM=100&VIEWPORT=&SEARCHCONFIG=param(SEARCHCONFIG)&DISPLAY=param(DISPLAY)&HIGHLIGHT_KEYWORD=undefined)

[3] James Kelly, ‘The historiography of the penal laws’, in J Bergin, E Magennis, L Ní Mhunghaile and P Walsh (eds.) New perspectives on the penal laws (Dublin, 2011), p. 38.

[4] Oliver Rafferty, Violence, Politics and Catholicism in Ireland, (Dublin, 2016), p. 231.

[5] Alan George Lewers Shaw, Convicts and the colonies: A study of penal transportation from Great Britain and Ireland to Australia and other parts of the British Empire, (Melbourne, 1977), p. 167.

[6] Shaw, Convicts and the colonies, p. 169.

[7] Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: A history of the transportation of convicts to Australia 1787-1868, (London, 1988), p. 181.

[8] Shaw, Convicts and the colonies, p. 166.

[9] Shaw, Convicts and the colonies, p. 150.

[10] See Patrick O’Farrell, The Catholic church in Australia (Melbourne, 1968).

[11] Costello, Botany Bay, p. 45.

[12] Costello, Botany Bay, pp 45-46.

[13] ‘A short account of some of the principle offenders lately executed’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 March 1804. (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/626091?searchTerm=executed&searchLimits=exactPhrase)

14] Costello, Botany Bay, pp. 46.

[15] ‘Regulations’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 24 April 1803 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/625535?searchTerm=regulations&searchLimits=l-decade=180)

[16] ‘Proclamation’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 24 April 1803. (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/625538?searchTerm=proclamation&searchLimits=l-decade=180)

[17] ‘Insurrection’, Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 11 March 1804 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/626075?searchTerm=insurrection&searchLimits=)

[18] ‘Proclamation’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 11 March 1804 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/5868)

[19] Costello, Botany Bay, pp 50-52.