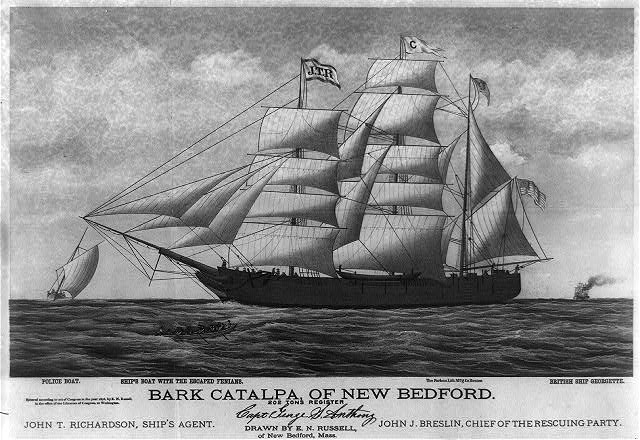

Illustration by E.N Russell of the Bark Catalpa of Bedford, 1876. Source: Map of Time: A trip into the past

The Catalpa rescue of 1876 had a significant effect on the Irish immigrant experience in Australia in the years following its occurrence and was a contributing factor in the shaping of the Australian nation and identity. This incident refers to the rescue of six I.R.B prisoners in 1876 from Fremantle prison which was located near Perth on the coast of Western Australia. Its significance lies in the fact that it was regarded by the British as a humiliation. This prison was supposedly one of the most secure in the British Empire. The fact that it was infiltrated by a crew of Irish Fenians among others meant that it was considered an embarrassment and an outrage by Australian colonists and the British government. Various newspaper articles from the time and the years that followed highlight the views held by British-Australians and Irish-Australians on the event, the prior seeing it as an outrage conducted by dissidents and the latter as a valiant retaliation. By examining this case study, an insight into the experiences of the Fenian convicts at Fremantle can be gained and the effects the rescue had on the Irish immigrant experience and the shaping of the Australian nation can also be clarified.

Disorder in Ireland, conflict in Australia

Ireland and Britain experienced a turbulent relationship throughout the nineteenth century. The land war in Ireland was one of the contributing factors to these tensions and resulted in the rise of conflict and violence in Ireland by what was known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood or the Fenian movement.[1] This was an anti-British establishment movement which sought to gain Irish independence by any means. In order to address the violence which was becoming an issue, the British government sentenced Fenian leaders and members to exile in remote prisons in the newly founded penal colonies of Australia. Sixty-two of these dissidents were transported to the penal colony of Western Australia in 1867.[2] The inclusion of these men caused conflict with many British-Australian colonists protesting over the deportation of the Fenians to Western Australia. The arrival of another ship of convicts was one issue that angered British-Australian colonists because it had already been stated by the British government that the previous ship of convicts would be the last to arrive in Western Australia. The inclusion of Irish rebels on the ship also made it far worse. There was a distinct conflict between Fenian prisoners and colonists in Western Australia. One Fenian prisoner, John ‘Galtee Boy’ Casey, for instance, stated his frustration with the Western Australian colonists in the Irishman: ‘Western Australia’s population can be separated into two different classes of people -the actual prisoners and the ones which deserve to be prisoners … all are equally dishonest. What more could be expected from a nation of convicts and felons’.[3] There was a sense of division amongst the community and the conflicts which had emerged in Ireland between the Irish and British colonists were now mimicked in Australia.

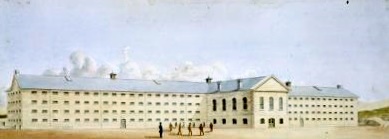

Henry Wray, illustration of Fremantle Prison, 1869. Source: Royal Sappers and Miners in Western Australia

Among the new arrival of Fenians were six who would escape Fremantle prison by way of the Catalpa whaler sent by John Devoy which arrived at Bunbury in Western Australia in March 1876. The experiences of the Fenian convicts in Fremantle were made evident in a rescue plea letter sent by prisoner James Wilson to John Devoy in 1873. Devoy was himself a former Fenian who had been exiled to the United States for ‘mutinous behaviour’ whilst his comrades had been sent to Fremantle prison on the coast of Western Australia.[4] The letter written by James Wilson, one of his former comrades, was a plea for rescue from what he referred to as a ‘living tomb’.[5] This letter provides an insight into their experiences in remote prison institutions such as Fremantle with Wilson writing: ‘What a death is staring us in the face, the death of a felon in a British dungeon, and a grave amongst Britain’s ruffians. I am not ashamed to speak the truth, that it is a disgrace to have us in prison today’.[6] This letter inspired John Devoy to rescue his former comrades from Fremantle prison by any means. He organised for a whaler with a crew to be sent to the coast of Western Australia and for a rescue plan to be devised by Breslin, an associate of his.

Escape!

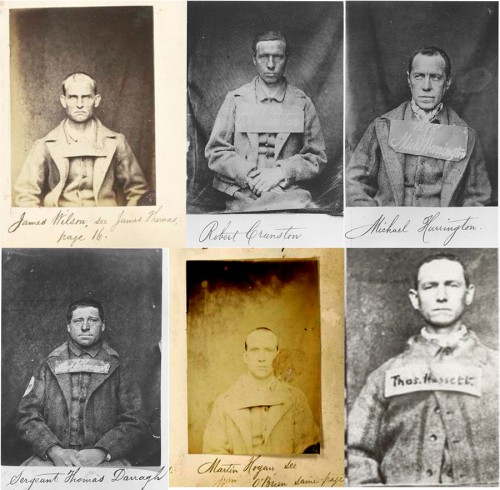

John J. Breslin, another Irish Fenian, also played a pivotal role in the rescue of these men. Breslin arrived in Fremantle months before the Catalpa ship. He assumed the identity of an American business tycoon who was interested in investing in lands in Western Australia. He utilised this persona to gain access to the Fremantle prison in order to devise a plan, which he outlined in his witness account of the event just a few months later: ‘I visited the prison, or as they call it in the colony, “The Establishment”, and was shown through the interior by a superintendent, and found it to be very well guarded. By the 1st of Jan 1876 I managed to have had several interviews with Wilson and determined the plan for escape’.[7] These meetings with Wilson enabled Breslin to devise his plan for the rescue of the six prisoners: Thomas Darragh, Thomas Hassett, Robert Cranston, Martin Hogan, Michael Harrington and James Wilson.

Individual mugshots of the Irish Fenian prisoners known as the Fremantle Six on their arrival to Fremantle prison in 1867. Source: Smithsonian Magazine

On 17 April 1876, each of these men abandoned their work posts, which were all outside of the prison grounds, and were met by Breslin nearby to be escorted to the shore where they would row out to international waters where the Catalpa whaler was anchored.[8] The crew were quickly followed by the Georgette which was a steamer boat occupied by guards from Fremantle. The steamer fired one cannon near the Catalpa as a warning but according to one news report: ‘The Catalpa hoisted the American flag on international waters, if the Georgette was to fire on her it would be considered to be an act of war’.[9] The whaler was then left to leave with the escapees on board. There were mixed reactions to the escape. The rescue was believed by newspaper journalists of the time to have heightened tensions which already existed between Irish convicts and British-Australian colonists in Western Australia. The colonists could not comprehend how these Fenians had escaped one of the most well-renowned high security prisons throughout the British Empire. The Rockhampton Bulletin, which was predominately pro-establishment in the nineteenth century, wrote days after the event:

It seems humiliating that a Yankee, with half a dozen coloured men and a group of Fenians should be able to come into our waters and carry off six of the most determined of the Fenian convicts – all the unreleased military prisoners – and then to laugh at us for allowing them to be taken away without making any effort to secure them.[10]

The Argus newspaper also demanded that the home government should ‘seek and obtain redress for this outrage’.[11] Such newspaper articles highlight the anger by the Australian colonists at these Fenian escapees which undoubtedly contributed to the creation of a negative view of the Irish immigrants living in Western Australia at the time. It is also evident from John Casey’s account in the Irishman that conflicts between the two communities had already emerged and this event only drove a further wedge between both communities.

Shaping Australian identity

Photo of the six wild geese monument at Rockingham, Western Australia, which symbolizes the escape of the Fremantle six in 1876. Source: ABC Australia News ABC Australia

For the Irish immigrants living in Western Australia, there was a sense of success amongst the community. Newspapers such as the Freeman’s Journal (a version of the Irish newspaper created for the Irish population in Australia), commended the escapees for what they considered to be a ‘valiant and ingenious escape’ and mentioned how there was a ‘particular sense of excitement’ amongst the Irish community in Western Australia.[12] This excitement even extended over to the average Irish immigrant with no prior Fenian involvement. A song known as ‘The Wild Geese’ was created to honour the bravery of the escapees. The song, however, was subsequently banned by the British government and its singing was considered as an act of treason for a number of years after the event. The lyrics were first published in Australia in the Southern Cross newspaper in 1903: ‘Then come all ye screws, warders and gaolers, Remember Perth Regatta day, take care of the rest of your Fenians, or the Yankees will take them away’.[13]

The Catalpa Rescue helped to shape the nation of Australia by creating a sense of identity amongst the population of Western Australia and had a profound effect on Western Australia and the development of its culture. The song and remembrance of the event is deep embedded in Western Australian culture to this day. A monument was erected in 1976 at Fremantle to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the rescue.[14] What was once considered to be an ‘outrage’ and a treasonous act in the years after the rescue’s enactment was remembered by the turn of the twentieth century as a pivotal moment in the history of Western Australia. The conflicts which once existed between Irish convicts and British-Australian colonisers had by then diminished to large extent. By the turn of the century even the more conservative of Australian newspapers commended the escapees for their cunning and bravery. After the death in 1904 of one of the crew on the Catalpa who assisted with the rescue, the Southern Cross newspaper reported how a monument was to be erected by the people of Western Australia in his honour which was worth 1,500 dollars.[15] This was for a man who had been considered to be a treasonous criminal in the 1870s.

It is evident from the primary material consulted that the Catalpa rescue was dominated by Irish involvement. The experiences of Irish convicts at Fremantle are evident in the correspondence between Wilson and Devoy in 1874. The account given by John Breslin which was mentioned also provides insight into his experiences. The newspaper articles analysed convey the various views on the event and how these views affected the Irish immigrant experience. The event created a less desirable image for the Irish living in Western Australia who already faced conflicts with colonisers prior to the rescue. Perceptions about the event changed, however, over time and by the turn of the century it is clear that the rescue was respected and considered an important part of the Western Australian spirit and culture. Today it is still embedded in Western Australian culture and has helped shape the way in which Australia is perceived today.

REFERENCES

[1] Paul Bew, Land and the national question in Ireland, 1858–82 (1979).

[2] Philip Fennell, ‘History into myth: the “Catalpa’s” long voyage’, New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, 9 (2005), p. 78

[3]John Casey, The Irishman, 4 June 1870, in John Sarsfield Casey (ed.), The Galtee Boy, A Fenian Prison Narrative (Dublin, 2004), p. 64

[4] Brad Manera, ‘The Fenian escape: as Perth celebrated Easter in 1876, a US whaling ship helped six Irish convicts escape from Fremantle Prison’, Wartime (Australian War Memorial), 16 (2001) pp 24-27: 25

[5] Letter from James Wilson to John Devoy, 4 September 1873, in Philip Fennell and Marie King (eds), John Devoy’s Catalpa Expedition (New York, 2006), p. 193.

[6] Letter from James Wilson to John Devoy, 4 September 1873, in Philip Fennell and Marie King (eds), John Devoy’s Catalpa Expedition (New York, 2006), p. 193

[7] Narrative of Mr. John Breslin, ‘The Escaped Fenians’, Advocate, 28 Oct 1876, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/170433731?)

[8] PhilipFennell ‘History into Myth: The “Catalpa’s” Long Voyage’, New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, 9 (2005), p. 78

[9] ‘Fremantle Port Topics’, Western Australian Times, 21 April 1876, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2975872?searchTerm=catalpa%20rescue&searchLimits=sortby=dateAsc)

[10] ‘Escape of Fenian Prisoners’, The Rockhampton Bulletin, 22 June 1876, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/51904577?searchTerm=catalpa%20rescue&searchLimits=#)

[11] ‘Escape of Fenian Prisoners from Western Australia’, The Argus, 7 June 1876, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5890964)

[12] ‘Who the escaped prisoners Are’, Freemans Journal, 29 July 1876, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/115303121?searchTerm=catalpa%20rescue&searchLimits=sortby=dateAsc|||l-title=464)

[13] ‘The Fenian’s Rescue’, Southern Cross, 27 March 1903, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/166958970?)

[14] Brad Manera, ‘The Fenian escape: as Perth celebrated Easter in 1876, a US whaling ship helped six Irish convicts escape from Fremantle Prison’, Wartime (Australian War Memorial), 16 (2001), p. 27.

[15] ‘West Australian Fenian Exiles’, Southern Cross, 5 Aug 1904, National Library of Australia’s Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/167035573?)